Back, and Forth: Old world becomes new

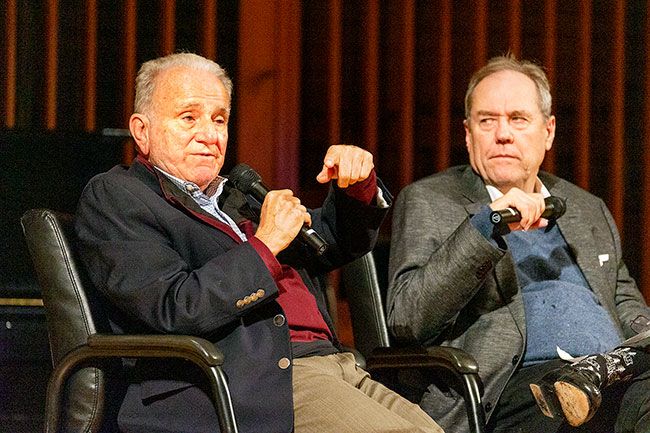

The passion for journalism remains for Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and lawyer Steve Kurkjian, who spoke Nov. 9 in Ice Auditorium at Linfield University.

Kurkjian told the 50 or so people in the audience that he finished his law degree after making a decision, a year from completing it, that he wanted to become a journalist. He joined The Boston Globe in the 1970s and went on to become founding member of its Spotlight investigative team.

Being a member of the bar has given him an advantage at times, said Kurkjian, 78, who shared conversation on stage with NW Media Fest patron Neville Johnson, himself an author and attorney.

“In reporting, you don’t want to give the upper hand in the conversation, and lawyers don’t want to give the upper hand,” Kurkjian said.

“I always felt it was my beguiling, friendly nature that got to be known at The Globe as being able to get the interview. I just kind of figured it out.”

News-Register reporter Scott Unger wrote an account on another talk Kurkjian delivered during the NW Media Fest. Published Nov. 11, it can be found at newsregister.com.

Be firm, and honest, with recalcitrant sources, Kurkjian advised. He said he was happy to have the chance this week during the Media Fest to share his views with potential future journalists.

“I tell people, ‘I appreciate that you are busy. I still have questions. People need to know. I’ll get it right, but people need to hear it from your own voice.’

“If you can convince people why it’s in the public’s best interest to speak and say what’s at the center of this, you have a fighting chance to get them to talk.”

Among his most dramatic accomplishments was persuading a Boston Archdiocese priest to go on the record about the cycle of sexual abuse by priests.

He recounts telling the disgraced priest, “You say, ‘you can’t talk.’ You know that this is a cycle of abuse that has gone on for decades, and not just in Boston, and it’s going to go on for decades, until we get people who are caught in the cycle of abuse to tell why it’s present, what’s going on with the clergy that allows it to continue.’”

He uses his tape recorder unless asked not to, telling his sources, “I need to look you in the eye. What you are telling me is really important, and I don’t want to be looking at my note-taking. I want to get it right.”

Kurkjian got a laugh when he added, “When they start saying the wrong things, I push the tape recorder a little closer, and they know it.

“I’m honest and I let them know, ‘there is a problem that has landed on their doorstep, that their agency has been found to be corrupt, or wasteful, and they’re in charge of that agency and need to speak’.”

Getting results can happen “by being as honest as you can, and being present.”

Kurkjian told this audience, “Thank you for letting me talk about my past, but also my present,” and that present is an outgrowth of what he calls “the toughest story I ever had to do” -- telling the personal side of the early-20th century Armenian genocide by the Ottoman Turks, and the continuing “Armenian immigration experience,” as he calls it.

“It was not just my story. It was the story of every Armenian family you meet in Boston,” Kurkjian said.

“My parents are Armenian, but I didn’t know my heritage. Growing up it was ‘You’re American. That’s old country problems,’” he said.

As a boy in 1915, Anooshvan Kurkjian saw his father killed. Months later, he lost a brother and a sister during a 350-mile walk to safety in Syria.

Placed in an orphanage, he came to the U.S. eight years later. He went on to become an artist.

“We found refuge and opportunity,” Steve Kurkjian said of Armenian immigrants like his father. We flourished … because of the protection this country offered and the opportunity it offered.”

His father, as with most Armenian elders, never talked about his experience, Kurkjian said, explaining, “It was too painful.”

While in his 80s, his father told his Steve’s sister that he wanted to visit Turkey. “My sister calls me and says, ‘I’ve got an assignment for you.’”

Their father wanted to see his childhood village in eastern Turkey. And he wanted to paint it.

“It took some locating,” Kurkjian said. But through a guide in what is now Kurdish territory, “We found our way there, we found a patch of land he said looked familiar to him.

“It was very powerful to me, so powerful I have dedicated myself to writing stories about the Armenian immigration experience,” Kurkjian said. “Not so much the hardship, but what I want to capture is the miracle that this provided us. I tell my kids, each of us has been given a piece of this miracle.”

Johnson interjected that reporting on Armenia helped convince the Obama administration to formally declare as genocide the killing of 1.5 million Armenians by the Ottomans starting in 1915.

Kurkjian noted that “the American government has tolerated excesses of the past, and current, as Turkey is a member of NATO, and the sense of ‘that’s the old country, in-the-past problems, let’s not throw sand in their faces’.” Johnson added, “you can go to jail in Turkey for calling it genocide,” as has happened to Turkish journalists.

“The issues remain fervent,” Kurkjian said, “and it is good to talk with young people, to say that these are the important issues: finding causes that will energize and keep you vibrant, that’s what this blessing of life is all about, and there is no better way to do it than to create a newspaper story. Don’t shy away, it’s still the best work that you can do.”

Comments