Randy Stapilus: Exploding electrical demand challenges region's capacity

The Northwest Power Planning Council was formed in 1981 in response to concerns in the area about the future availability of energy and the potential impact on power production on various business sectors and on the environment, especially fish runs.

Formed by Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Montana, the Portland-based commission was high-profile for a while, even controversial. But it fell off the public radar after completing its regional energy and environmental plans.

Now called the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, its mission in recent years often has focused more heavily on fish runs than on energy production. And that’s brought criticism.

In 2013, one of its original members, Chris Carlson of Idaho, called for its dissolution.

He said the council’s “shortcoming in producing a viable plan to restore the wild salmon and steelhead fishery runs decimated by the four lower Snake River dams” was reason enough to put it “out of its misery.” He called it a “gargantuan waste.”

Carlson has not been alone in questioning the council’s ongoing role. And other critics are pointing at a different target — a looming regional power shortage.

Since the period four decades ago when planners expected the region to run far short of electricity, conservation has taken hold, new power sources have been developed, grid lines have been strengthened and renewable energy such as wind and solar have been installed. Lately, however, the Northwest seems on the verge of something approaching a 1980-style regional shortage.

In a December report, Sarah Smith, research scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California, said: “The electricity use had somewhat stabilized for a few years [in the 2010s]. We are in that growth phase again and climbing up what’s hopefully an s-curve and not an ‘exponential-forever’ curve.”

That brings us back to the council. It could serve the region in a big way by adjusting its mission to what could become the largest resource crisis the region has seen since its early days, what with new mass power users pouring into the region.

Data centers may be among the largest.

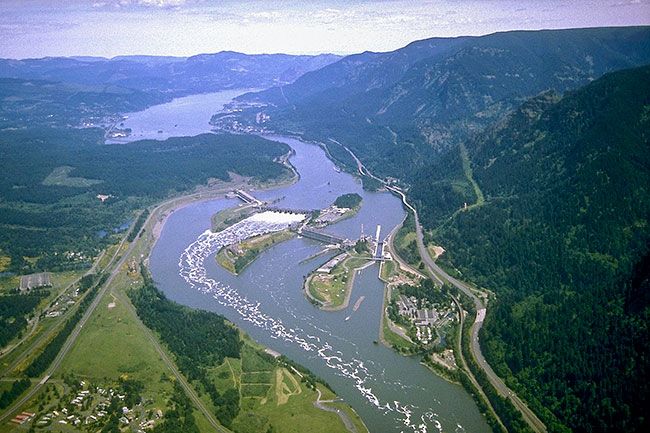

The Northwest, and especially the Columbia River area, have become highly popular locations for data centers helping companies such as Amazon and Google handle their online traffic. But these centers use an immense amount of electricity, and in some cases, water as well.

This has had a massive effect on electricity rates for Oregon customers. That’s led Portland General Electric to exact large rate increases two years in a row.

This year’s Oregon legislative session is likely to see measures intended to block tech companies’ power demands from boosting residential rates even higher. Two placeholder bills on studying utilities have been filed, Senate Bill 128 and House Bill 3158, and Rep. Pam Marsh, D-Ashland, is working on another.

“People who are our largest energy users should be paying for the cost of their energy. That’s just a basic consumer protection issue here,” she told The Oregonian/OregonLive.

The Citizens Utility Board, a Portland-based watchdog group established by voters in 1984 to represent consumer interests, also has made energy affordability its top priority for the 2025 session.

The group said it is “working to find long-term solutions to address the energy affordability crisis too many in Oregon are facing,” indicating, “We will also be focusing on adding more consumer protections for utility customers.”

The problem stretches beyond Oregon, however, and the Legislature’s ability to contain it may be limited. If electric utilities are obliged to add more expensive power sources in coming years, someone will have to pay for them.

Much the same can be said for cryptocurrency management hubs, which also require immense amounts of juice. They will likely will be seeking out low-cost areas such as the Northwest as well, especially if the new Trump administration carries through with promises to foster crypto industry growth.

Electric vehicles, both passenger and commercial, constitute a third new source of pressure on the electrical supply.

Electric vehicles have become notably popular in Oregon. As of November 2023, more than 83,000 were registered in the state.

As a result, the number of charging stations has exploded. By late 2023, there were 2,960 spread among 1,182 sites, and the count has no doubt risen significantly since.

On Jan. 1, a new state Department of Environmental Quality requirement says that at least 7% of all Class 8 heavy trucks sold in Oregon must be electric, and it plans to raise that threshold annually. That led Daimler, an international truck manufacturer whose North American headquarters are located in Portland, to stop selling electric trucks in Oregon for a month.

The rule change reflects a shifting motor vehicle marketplace and a massive new user of electric power, putting yet more pressure on the Northwest power supply.

Comments

Bigfootlives

Nuclear. It could be the smartest thing Oregon has done in 75 years.

Moe

For starters, how about this effortless policy:

No data centers.

No state DEQ mandates for EVs.

(The notion of an EV heavy truck is absurd on its face.)