Offbeat Oregon: ‘King of moonshiners’ was an old-time music legend

Among musicians and fans of old-time string-band music, Benjamin Franklin Jarrell is basically royalty.

As a member of one of the most influential bands from the golden age of old-time music — DaCosta Woltz’s Southern Broadcasters — old Ben helped preserve that classic Appalachian-mountain style of fiddle-and-banjo string bands. His son, Thomas Jefferson “Tommy” Jarrell, is maybe the most influential old-time fiddle player even today, 40 years after his death.

In Oregon, though, during the years of Ben’s youth, he was a different kind of royalty. The newspapers called him “The King of the Moonshiners.”

And by all accounts, anyone lucky enough to acquire a quart or two of his product had to agree that the title was his.

Ben Jarrell was born in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina in 1880, and he was the son of a licensed distiller, from whom he learned the trade. The Jarrells were particularly famous for their apple brandy, and Ben was always meticulous and professional in his craftsmanship.

When Ben left the nest, he left the distillery and opened a country store in his home community of Round Peak. But he kept up his liquor-making as a sort of side hustle, making the stuff on the down-low, untaxed, and selling it to friends.

“I kept up moonshining till North Carolina voted for Prohibition (in 1908),” Ben later told legendary Portland Journal reporter Fred Lockley, “and then I quit, because I believe in the rule of the majority, and I wouldn’t go against the express will of the fellow citizens of my state.”

The loss of income must have hurt, though, because Ben soon had a problem at his business.

“I was running a store back home, and was too easy, giving credit to the folks I had been raised with. I couldn’t turn them down,” he told Lockley. “I finally got in debt over $6,000. I can’t abide not being able to settle my obligations, so I came out here (to Oregon) to make some big money quick to get my debts cleaned up.”

By this time, it was 1916. Nationwide Prohibition wouldn’t happen until 1920, but Oregon got an early start on it, and the Beaver State had just gone “bone dry.”

“In North Carolina, good liquor was going for $1 to $1.50 per gallon,” writes historian Bruce Haney in his book, Oregon Moonshine. “In Oregon, now that Prohibition was in effect, garbage bathtub liquor was going for $10 to $12 per quart. If Jarrell wanted to raise enough money to get out of debt, Oregon was the place to do it.”

“I figured if people out here were bound to get whiskey I would furnish it to them a good turn by making a high grade of moonshine instead of the hair oil, varnish and painkillers they are using,” he told Lockley.

Ben journeyed across the country to the Oregon, put in four days of hard work, and headed back home $1,100 richer.

A year later, he made another business trip to Oregon, and this time he brought two top-grade 65-gallon copper stills with him. These ran wide open for two solid weeks, churning out 45 gallons of top-quality white lightning every day, after which Ben headed back home to North Carolina with $2,300 in his pocket.

Already halfway out of debt, Ben scheduled one last hurrah in Oregon — an extended visit in which he hoped to make $5,000. That would retire his debt completely and leave him with a little something left over with which to get into a less hazardous line of work back home.

Unfortunately, Ben’s reputation had started to spread in Oregon, due to the quality of his product. Also, law enforcement officers had started figuring out how to sniff out a big liquor operation, and they had started watching the stores for bulk purchases of stuff like sugar, yeast, dried fruits, and corn.

When one of Ben’s helpers rolled into Walla Walla and bought a truckload of cornmeal, the transaction was noticed; and when the helper returned with the goods, he also brought a new customer with him. The customer sampled the product, pronounced himself delighted with it, bought a gallon or two, and headed off … to the law enforcement agency that he worked for.

A few days later Umatilla County Sheriff Tillman “Til” Taylor arrived on the scene at the head of a 14-man posse to shut the show down. They pounced upon it late at night, after Ben had gone to sleep, and caught all three of the moonshiners by surprise.

The moonshiners were marched back to where the posse members had parked their automobiles earlier in the night. Of course, it was pitch dark, and they were deep in the woods; so they made camp by the cars for the night, planning to head back to civilization after daybreak.

“They made a little campfire near the autos,” Ben told Lockley, “and as we sat around the fire we all took a few drinks from the keg they had brought along as evidence. I think all drank but Til. He wasn’t thirsty, he said. As they were all talking about what good luck they had in nabbing us I made a sudden dive like a cottontail into a bunch of small pines. There was a hummock about 40 to 50 feet from the fire. I dropped at full length behind that.”

Ben stayed there the rest of the night, figuring that if he tried to run for it, they’d catch him for sure. He stayed put while the posse scampered around trying to pick up his trail. Finally, they all came back to the campfire and sat around glumly talking about how fast he must have run to get away from them like that.

“No use cussing about him,” Til said. “It was our own fault. I don’t blame him any, I would have done the same thing.”

Ben, of course, hit the road as soon as he safely could. He’d made it across the state line into Idaho before Sheriff Til traced him; he’d stopped for a visit with an old neighbor who lived there, preparatory to heading back home to North Carolina empty-handed.

Til Taylor had no jurisdiction in Idaho, but he came out anyway. Ben was away from the house when he arrived, so Til left him a message to telephone him. When Ben returned to the house, he did; Til was out, so he left a “tag, you’re it” type message at the hotel.

When the two finally connected, Til laid the pitch on Ben: Come on back to Oregon with me, he urged, and take your medicine. Otherwise the prosecutor will probably get North Carolina to extradite you, and you’ll end up getting arrested in front of all your family and friends, and it’ll be a much bigger hassle than it’ll be if we just take care of this now.

Ben said that made sense to him, and that if Til would let him just come back with him, like two friends traveling on the train together, with no shackles or extra law-enforcement officers, he’d go. And, of course, so he did.

He ended up drawing a six-month stretch in the Oregon State Penitentiary. After getting out, he didn’t want to go home empty-handed, so he moved to Astoria and set up another still.

But the magic seems to have been gone, or maybe the cops had just learned a trick or two. He was soon busted again, and back in the slammer for another six months.

While he was “in durance vile” for the second time in Salem, he got word of Sheriff Til Taylor’s death. Til had been shot in the back by an inmate during a jailbreak at the Umatilla County Jail; somehow a gun had been smuggled into the place.

Ben, from prison, scraped together $5 and sent it as a contribution to the Til Taylor Memorial Fund. “I cannot express how sorry I was to hear of his tragic end,” he wrote, in the letter that enclosed the contribution. “It is a shame that a brave, good man like Til Taylor should have been shot from behind by a dirty cur.”

Later that year, Ben was released from prison. This time, he played no games; he just hopped on a train for home.

The following year, in 1921, Ben dropped a line to his Portland Journal friend, Fred Lockley. “I was known in your county as the King of the Moonshiners,” he wrote. “Here I am known as Mr. B.F. Jarrell. … I have a nice business here and I believe I will do well. Sometime write me a line or so, for I liked Oregon pretty well if they hadn’t pestered me so.”

When he wrote that letter, Ben had just moved with his family from Round Peak to the nearby town of Mount Airy, 12 miles east, and opened a store there. In Mount Airy, of course, Ben’s childhood friends were no longer able to come and charge groceries on account, so he was able to stay out of debt and prosper.

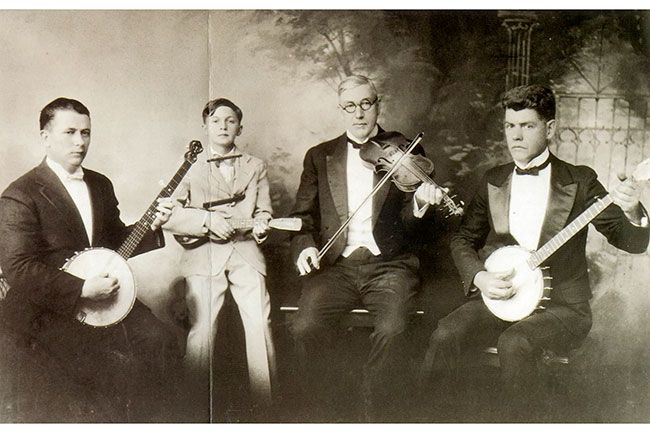

In 1927, he joined patent-medicine seller DaCosta Woltz and banjo player Frank Jenkins on a journey to Richmond, Ind., to record 18 songs for Gennett records as Da Costa Woltz’s Southern Broadcasters. It was then that he added “founding father of the Old Time Music scene” to his “King of the Moonshiners” title.

As far as I know, Benjamin Franklin Jarrell never returned to Oregon. But you’d better believe his voice, and the sound of his fiddle, did!

(Sources: Oregon Moonshine: Bootleggers, Busts and Brawls, a book by Bruce Haney published in 2023 by The History Press; “Jarrell, Benjamin Franklin,” an article by Cecelia Conway in the Dictionary of North Carolina Biography (ed. William S. Powell) published by UNC Press in 1988; correspondence with Morgan John of Seattle old-time music band Four Dollar Shoe)

Finn J.D. John’s most recent book, “Bad Ideas and Horrible People of Old Oregon,” was published by Ouragan House last year. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.

Comments