Patrick O’Connor: County stages robust rebound from devastation of pandemic

In February 2022, Yamhill County’s total employment was 80 jobs above its pre-pandemic level of February 2020. In just under two years, the county had already added back the nearly 5,800 jobs lost in the spring of 2020.

Many things in this pandemic have been unprecedented, and that includes the speed of the employment recovery.

In the Great Recession, Yamhill County lost 2,790 jobs between its pre-recession peak and the trough of September 2010. Though that job loss was significantly smaller, it took the county seven years to fully recover.

Yamhill County has not been alone in its rapid pandemic recovery. Other counties in Oregon now boasting employment above pre-recession levels include: Baker, Crook, Deschutes, Gilliam, Harney, Linn, Morrow, Wallowa and Wheeler.

Except for Deschutes and Linn, these counties are rural. In general, the more rural the county, the faster the recovery in Oregon — and vice versa, as Multnomah trails the pack.

This is certainly different from what we experienced after the Great Recession, or the recession of the early 2000s. In both those cases, employment recovered faster in Portland Metro than other parts of the state.

As of May 2022, the state as a whole had regained 90% of the jobs lost in the spring of 2020. But it remained short of full recovery.

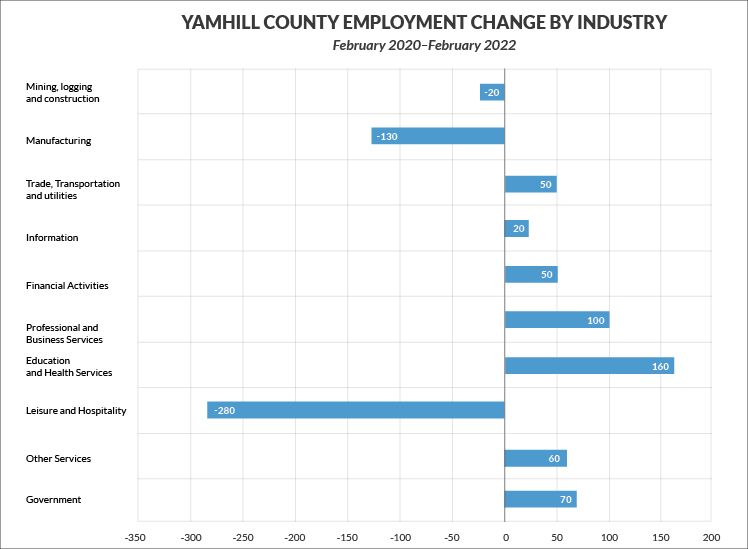

We now have employment data for Yamhill County through May. However, because our industry level data is not seasonally adjusted, it’s best to compare data from February 2022 and February 2020 to see where industry employment stands today, compared with its pre-recession level.

Using the same month to compare gives us a better “apples to apples” look rather than comparing different months of the year, as seasonal changes could distort the picture.

We can see in the chart that manufacturing and leisure and hospitality are the two sectors with the largest employment gaps remaining from pre-recession levels. Not coincidentally, these were two of the three industries that experienced the sharpest job loss.

Private educational services also experienced a steep job loss during the pandemic, but its employment level has bounced back. Employment in that sector now stands above its pre-recession level, albeit only slightly.

Leisure and hospitality has certainly been the most visible sector impacted by the pandemic. Restaurants account for more than 80 percent of the sector’s employment in Yamhill County, and they were hard hit.

Between February and April 2020, Yamhill County’s leisure and hospitality employment fell almost 50%, declining from 3,710 jobs to 1,890. It has since added back 1,540 of those jobs, 85% of what it lost, leaving it with 280 to go.

Statewide, the leisure and hospitality rebound also stands at 85%. That is reflected in slower-than-average recovery in coastal counties, where dependence on tourism is greatest.

Yamhill County’s manufacturing employment declined 1,010 jobs in spring of 2020, a 15% employment falloff. The county has regained 880 or 87%.

The losses were concentrated in beverage manufacturing, food manufacturing and miscellaneous manufacturing, the latter including A-dec in Newberg and Meggitt in McMinnville. The sector remains 130 jobs short of its pre-pandemic level.

Colleges and universities typically maintain relatively stable during recessions.

However, some workers will take time off to continue their education. As a result, both two- and four-year colleges experienced enrollment gains during the Great Recession.

That could not have been less true during the pandemic recession. Across the state, enrollment declined.

Yamhill County is home to two universities, so its private educational services sector experienced deep employment losses. It shed 570 jobs, or 18 percent, from February 2020 to February 2021.

Some of that stemmed from reduction of faculty and staff, but student workers accounted for a large majority. As vaccinations were introduced and campuses began to resume on-campus learning, enrollment and employment began recovering.

In February 2022, Yamhill County’s private education employment stood 200 above its pre-recession level.

The chart groups health services with private education. Health service remains down 90 jobs or 1.6%, spread among hospitals, clinics and residential care facilities.

Other local sectors have joined in surpassing their pre-pandemic employment.

Professional and business services sector has added 100 jobs, up 4.8%; retail trade 120 jobs, up 3.3%; information 20 jobs, up 8.7%, given its small size; financial activities 50 jobs, up 4.3%; other services 60 jobs, up 5.2%.

Other services is a sector that includes a diverse group of industries that don’t fit in other sectors. This includes religious, grantmaking, and civic organizations; businesses that repair and maintain machinery and equipment; and personal care services, such as hair and nail care, massage therapy and tattoo application.

Personal services experienced huge job losses, with 2020 employment dropping from 252 in March to 90 in April. As the state re-opened, it rebounded to 200 in July 2020 and has continued on an upswing ever since.

However, hiring challenges continue.

Prior to COVID-19, Yamhill County’s unemployment rate remained below 4% during all of 2017, 2018 and 2019. By the fall of 2019, it was down to a historic low of 3.1%. So employers had been dealing with a tight labor market for some time.

Almost overnight, unemployment shot up. It reached 11.7% in April 2020, just below the all-time high of 11.9%, logged during the Great Recession.

During the Great Recession, Yamhill County’s unemployment rate remained in double-digit territory for all of 2009 and 2010 — 24 straight months.

In stark contrast, it rebounded this time as Oregon’s economy began to reopen in the summer of 2020. By October 2020, it was back down to 5.9%, below its long-run average of 6.4%.

Local unemployment continued to fall through 2021. It dropped below 4% in October 2021 and slid on down to 3.3% in May 2022, just 0.2% shy of its all-time low.

Even though Yamhill County unemployment is nearing its historic low, similar to where it stood prior to the pandemic, there is one major difference — the number of job openings employers are trying to fill.

The Employment Department’s winter 2021-22 survey turned up 100,000 vacancies. The department’s winter 2019-20 survey logged just 43,000, and there is no reason to think things are different in Yamhill County.

Such a large number of vacancies makes it more challenging for employers to maintain, let alone expand, their workforce.

One measure of the tightness of the market is the ratio of unemployed workers to vacancies. In winter 2019-20, it was running 2-to-1. The 2021-22 survey shows it running 4-to-5, with vacancies actually outnumbering the pool of unemployed workers.

At the height of the Great Recession, there were six unemployed people for every job vacancy — long odds for job seekers. Today, however, it’s the employer facing the long odds.

Another measure is Oregon’s labor force participation rate, calculated by adding the number of employed and unemployed residents in the labor force and dividing that figure by the 16-and-up portion of the overall population.

The participation rate fell to 59.2% in April 2020, thanks to the pandemic. It has been rising ever since.

The May report pegged it at 63.5%, the highest reading in 10 years. That compared to a national rate, also uncharacteristically high, of 62.3% for May.

Then there’s the inflation issue.

We are currently experiencing the highest inflation rate in 40 years. And historically, high inflation and low unemployment aren’t able to co-exist for long.

A number of economists are forecasting a recession. Probably the best-known is Larry Summers, former secretary of the treasury.

The Federal Reserve Board is certainly aware of that risk.

It has been raising interest rates in order to tamp down inflation, hoping it can slow the economy without pushing it into recession territory. Whether it can steer us to the “softish landing” Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell is shooting for remains to be seen.

In its baseline forecast, Oregon’s Office of Economic Analysis is projecting continued job growth through 2022, with Oregon reaching its pre-pandemic employment level near the end of the year. It is projecting continued job growth in 2023 and 2024 as well.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office is also projecting continued job growth nationally in its May forecast. It is predicting the U.S. unemployment rate will remain below 4% through 2022, 2023 and 2024.

The office is also forecasting inflation will subside. It has projected a decline from the current 6.1% to 3.1% in 2023 and 2.6% in 2024 — nearing the Federal Reserve’s goal of 2%.

Of course, those forecasts could both be wrong.

I and my fellow economists don’t have a great track record for predicting recessions. We seem to be much better at performing the autopsy after the fact.

But right now, it looks as if the tight labor market currently being experience by the county and state is likely to continue, at least into the near-term future. There’s no evidence of imminent change.

Guest writer Patrick O’Connor has been serving as a regional economist with the Oregon Employment Department for 20 years, covering the Mid-Willamette Valley counties of Marion, Polk, Yamhill, Benton and Linn. Outside work, his hobbies include cultivating roses, playing golf and playing the guitar. He hails from Corvallis and his wife, Stephanie (Moore) O’Connor, hails from McMinnville. They make their home in Corvallis with their daughter, Nora.

Comments