Holiday traditions: Snow in Russia, art in America

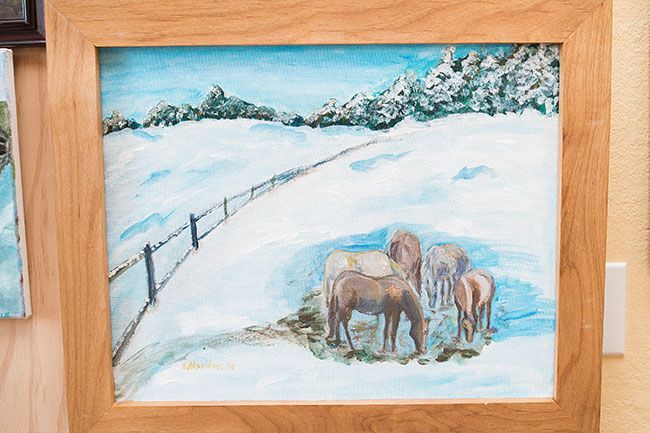

Artist Natalia Novikoff misses snow — real, Russian snow, the kind that once nearly covered her grandmother’s house or fell on the ice castles and slides her town built for the winter holidays.

“At least we get some snow here,” she said.

She enjoys McMinnville, where she’s lived since 2015. Even if snow falls only a few times a year, she enjoys the beauty of the seasons, especially autumn.

“Here, fall just mesmerizes me. I want to paint all the time,” she said, noting if she didn’t live in Oregon, she might not paint nature scenes.

She loves living so near the ocean. She likes to find remote beaches to walk while watching the waves.

She enjoys walking in the woods near Willamina, as well. The area reminds her of places in Russia, where she lived until marrying an American, Don Novikoff, and moving to the U.S. in 2010.

Novikoff grew up in the Ural region of Russia. Her “little town” of Kartaly was about the size of McMinnville.

Her family now lives in Magnitogorsk, a much larger city and home to a major metallurgical plant, she said. She has two brothers and a sister, all younger; between them, they are parents to her seven nephews and nieces.

Thanks to modern technology, she can connect with her family on a daily basis via Skype and Facetime.

Novikoff, 46, said she had a very good childhood. “I was a dreamer. I didn’t know about bad stuff,” she said. “I’m still an upbeat, positive person.”

She liked to play outside with her many friends. She and her siblings worked in their family garden and did chores around the house. “All the kids did,” she said.

Although her family was never rich, she said, “Dad was a go-getter. He could manage to find what we needed.”

Her father was a correspondent and photographer for the local newspaper. His photography may have sparked her own creativity, she said.

“He taught me to see the beauty around me.”

Novikoff didn’t consider art, though. “I knew others who could draw, but didn’t know I could draw,” she said.

Teachers noticed she was good with languages, so she was encouraged to become a language teacher. “Why didn’t I become a teacher of art?” she wonders now.

Christmas, as celebrated in the U.S., never crossed her mind, either. Dec. 25 was just another day in Russia in the 1970s and ’80s, although some overtly religious Catholics managed to mark the holiday.

“I didn’t even know about Christmas until 10 or 15 years ago,” Novikoff said. “Not as a child.”

In recent years, though, religion has become more acceptable in Russia. Some families even decorate a tree on Dec. 25.

But most celebrate “Russian Christmas,” a non-religious event, on a completely different date: Jan. 6-7. Her mother cooks a goose for dinner, and family members gather to mark the occasion.

It pales in comparison to what has always been the major celebration of the year: the coming of the New Year.

“It’s the most important holiday,” she said. “You meet the new year through the night. It’s like magic; it brings you new hope.”

Special foods are served for New Years, including a variety of salads.

One is called “Herring Under the Fur Coat,” with the “fur” being grated, boiled winter vegetables such as carrots, beets and potatoes. Novikoff makes the salad today, but uses salmon instead of herring.

She also still prepares a French-Russian salad with cubes of root vegetables, cubes of meat and mayonnaise.

“We use a lot of mayonnaise,” she said with a laugh, noting how Russians are starting to use other dressings for their salads these days.

Chicken or goose is served alongside the salads. In addition, perogies are on the table along with pelmeni, the Russian equivalent of ravioli, stuffed with beef or pork.

A variety of sweets are served on New Year’s and Russian Christmas. Pies and pastries are made with yeast dough and a selection of fillings. Cooks may make pies and cakes themselves, or buy them.

Novikoff baked when she was growing up. She still loves baking, she said, and her son Ivan, 17, enjoys her Russian specialties.

The Russian New Year’s party starts about 8 or 9 p.m., she said. The first order of business is eating and drinking in honor of the old year.

“At midnight, you meet the new year and eat and drink again,” she said.

The Russian president also speaks to the nation at midnight. Fireworks are set off. The party continues until 5 or 6 a.m.

The next day, families in Magnitogorsk and most other cities visit the huge ice slide created for the holiday. “They climb and climb up, then slide down,” she said of the longstanding tradition.

The slides are created in early December. People everywhere make ice castles and sculptures, as well, all of which are popular destinations on New Year’s Eve.

She recalled the year she was in ninth-grade. In addition to sliding, she and a group of her friends engaged in a tradition “guaranteed” to predict where they’d find their future husbands.

The game is called “valenki,” which also is the word for the stiff lining of winter boots. Girls wear only the lining as the game starts. Then they remove the valenki from one foot and toss it across the ice. The direction it’s pointing when it lands predicts the future.

“Then you have to jump out on one leg to get the valenki back,” she said. “It’s fun” — especially for your friends who are watching you hop.”

She and her friends also predicted the future with glasses of water, some of which contained salt and others sugar. “If it was sweet, that’s what your year would be,” she said, noting that “I always got something good.”

When she came to the U.S., Novikoff said, she found it odd that New Year’s celebrations are so low-key here.

Since moving, she’s made several Russian friends who live in Amity, Keizer, Vancouver and other nearby places. They meet in a central location to celebrate.

Back home in McMinnville, she paints on Saturdays and days off from her job at Crown Creations dental lab.

Art is her passion, a “place to put all my emotions,” she said.

But, having grown up thinking she wasn’t artistic, she didn’t start painting until she moved to the U.S.

She was living in California when she picked up a book of drawings and paintings in a book. Intrigued, she decided to try drawing herself.

She signed up for art lessons, too, and learned a variety of media — charcoal, pastels, acrylics. She used them all as she practiced doing still lifes.

At home following a lesson, she noticed a picture of a leopard cub on her calendar. She used acrylics to paint her own version of the picture. “It turned out well. I was surprised,” she said.

She left her first teacher when her family moved to McMinnville. She realized she could keep exploring different media and styles. “I felt free,” she said.

Novikoff joined local art groups, including one that meets weekly at the Presbyterian Church. “They love and cherish me, and I love them, too,” she said.

She has participated twice in Art Harvest, the Arts Alliance of Yamhill County’s annual studio tour.

During her first months here, she began experimenting with oil painting and created her first portraits, using her son and her husband as models.

“They looked like a boy and a man, but not like themselves,” she said. After more practice and encouragement from other artists, her subsequent portraits looked much more the subjects.

One shows the face of a young Nigerian girl. Novikoff was inspired not only by the child, but also by the toned paper on which she applied pastels.

“It was the perfect color for her skin,” the artist said; she just had to define the face and add details.

She said she focuses “mostly on expressions” when she paints people. “The eyes are just magic for me,” she said. “And I have to like the subject. I want to learn more and guess their character.”

These days, Novikoff works primarily in oils, although she still uses watercolors, charcoal, pastels and, occasionally, acrylics.

“Oils are easier to paint over if I change my mind,” she said.

She said she loves the process of going from start to finish. “I like the surprise element ... first it’s a white canvas or paper, then it’s something,” she said.

A painting may take three to five hours, she said. “I still like painting fast.”

She may start with a photograph or paint outdoors, using the scene before her as inspiration. She’s also done figure drawings using live models.

She may combine pictures or add touches from her imagination.

For instance, she painted a scene based on her aunt’s barnyard in Russia. It features two large chickens. She added some chicks to balance out the image, and called the finished piece, “Where have you been?”

Another of her paintings shows the face of a bovine, its nose prominent in the foreground. It’s a portrait of a real animal on her aunt’s farm. “His name is Handsome,” Novikoff said. “I really liked him.”

Novikoff has many photos of Russian scenes to inspire her. She takes her camera when she returns to her homeland every other year.

She also depends on her memory. “I want to paint my grandmother’s house,” she said. She has been sketching details she remembers, such as the way the house was almost covered with snow.

She chuckled about her descriptions of the house and her future paintings. “I shouldn’t tell you my plans,” she said, “because then they won’t come true.”

Comments