Offbeat Oregon: Fiery, explosive shipwreck gave Boiler Bay its name

A mile or two north of the picturesque little Central Coast town of Depoe Bay, there’s a little unassuming wide spot at the side of Highway 101 where you can pull off the road and park. There are a couple trails leading down to the sea from that spot, and at very low tides you’ll often see people there, climbing over the ridge and picking their way down to the rocky, forbidding shore below.

You’ll also sometimes see one of them stop to get a photo of a really incongruous thing at the top of the bluff. It’s a large, rusty steel pipe, wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, shaped like an air duct or maybe a ventilation stack on a steamship. The pipe towers about eight feet above the ground and is very obviously buried nearly that far into the dirt below.

That duct is one of two remaining large pieces left from what must have been the most spectacular shipwreck in West Coast history: The fiery, explosive demise of the steam schooner J. Marhoffer.

And yes, that huge piece of steam-engine ductwork is where it is, sticking out of the ground hundreds of yards from the bay, because it fell out of the sky and jammed into the ground like a giant Lawn Jart after being blasted into the air by the explosion.

Here’s the story:

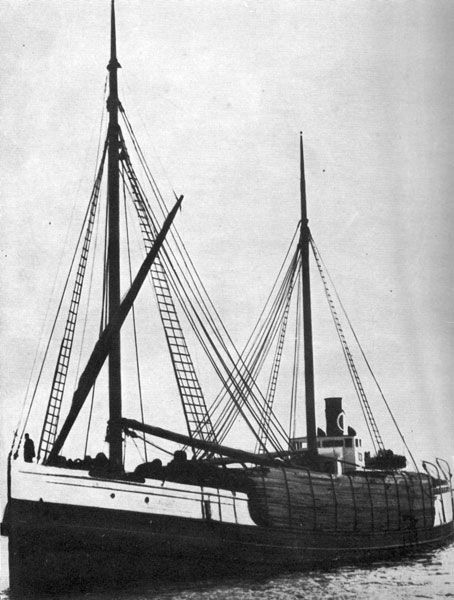

The J. Marhoffer was a 175-foot, 600-ton wooden steam schooner of the type that was very common in the coastwise lumber shipping business early in the 20th century. Your basic West Coast steam schooner of that era was basically an 1870s-style lumber schooner with a steam power plant below decks, and with a pair of masts that (usually) sails could be rigged on if conditions were good enough to justify it. They were slow and, when fully loaded, had a startlingly small amount of freeboard (the amount of hull exposed above the water, basically the distance from the deck scuppers to the water’s surface). They were designed to weather storms pretty well, but because they were coasters they weren’t expected to have to ride them out very often.

The Marhoffer was built by the Lindstrom Shipbuilding Company in Aberdeen, up in Washington’s Grays Harbor, in 1907. She was named after a businessman from Crescent City, Calif., in the heart of the northern-California “doghole port” part of the coast.

By the standards of the day, she was a fairly modern ship. Although built with wood, she was powered by a steam engine fired by oil, not coal or cordwood. That would turn out to be an important detail in the story of her demise.

On May 18, 1910, she was steaming north along the Oregon coast, having left San Francisco a few days earlier to deliver a load. She was on her way to Portland to pick up a fresh load, so she was in ballast at the time.

The weather was fair and the sea was mellow, and everyone was pretty relaxed. The engineer had left the engine room in the charge of his assistant and gone to take a nap in his cabin. The assistant was in the engine room, trying to get a gasoline-powered blowtorch to stay lighted. It was an unfamiliar design, and it was giving him trouble.

Apparently he overpressurized it, because suddenly it exploded in his hands, distributing burning gasoline all over the engine room.

The assistant was dazed and burned but otherwise unhurt. However, by the time he recovered his wits, the whole engine room was on fire. A lot of fuel oil had spilled and spattered here and there in that engine room over the previous two years of service, and once that was on fire, there was no smothering it.

The assistant engineer ran to get help, closing the door to try and prevent the fire from spreading.

Crew members raced to the scene. Captain Gustave Peterson ordered the engine room flooded. But by this time, the fire had made the valve handles too hot to touch, and the fire had spread. Getting into the engine room was a complete no-go at this point, which meant no one could shut the steam engine off. The Marhoffer was trucking along at full cruising speed, a steady nine knots (10.4 miles per hour) and there was nothing anybody could do to stop it.

Peterson got the bow pointed at the shore, three miles off — luckily, the rudder control still worked — and gave the order to abandon ship.

This, of course, was no easy task. Clambering into a lifeboat and paddling away is something that’s hard enough to do when the ship isn’t roaring along at close to top speed and with choking smoke billowing out of every hatch. The first lifeboat swamped, pitching three sailors into the drink; but, luckily, the second lifeboat was launched successfully and was able to rescue them. Most likely a small crew got the boat underway and then the remaining members of the crew of 20, plus the captain’s wife, jumped overboard and were fished out of the drink and warmed up as best they could be. The ship’s dog, also, was rescued.

Then they retrieved the other lifeboat, righted it and bailed it out, and set out for shore.

Meanwhile, the Marhoffer, unmanned and unguided, thrashed onward through the waves toward the shore. Considering that the crew were about to land on a fairly remote seacoast, soaked to the skin and in at least two cases with injuries, having a burning steam schooner go before them to announce their plight had certain advantages. The sight of the ship, now trailing a thick column of fire and smoke, thundering toward the land, brought all the neighbors out of their houses and cabins and onto the bluff to watch, and assist.

Unguided, the steamer came ashore, behaving more and more erratically as her boiler pressure rose. She actually made a full circle, just missing the rocks, and just as she passed the shore one of her oil tanks burst, showering the nearby trees with burning oil. Then she looped back around as if to try again, and piled onto the rocks with an enormous crash, still under full power and trailing a column of smoke and fire like a floating volcano.

The ship heeled over and burned fiercely for a time; then her long-suffering boiler exploded with a thunderous blast, ripping chunks of wood and steel free and sending burning debris in all directions. One of those pieces of debris was, of course, the steel duct pipe that’s still sticking out of the bluff today, right where it fell. Luckily, neither the duct nor any of the other bits and pieces of burning wood and scalding steel that flew up into the air came down on any of the spectators who had gathered to watch the show.

As for the crew of the Marhoffer, in their two lifeboats, the ship reached the shore well before they did. Unfortunately, a misunderstanding as they pulled in close to shore caused them a great deal of trouble and probably sealed the doom of the ship’s cook, Frank Tiffney, who was the shipwreck’s only fatality.

As the men rowed shoreward, they made for Fogarty Creek, just north of Boiler Bay and almost within sight of the burning wreckage of their ship. Unfortunately, a woman on the shore there spotted them and started vigorously waving a red shirt at them from that spot, assuming that they would understand that she meant that this was where they should land.

To the sailors, though, it looked like she was waving them off, warning them of some danger. So they turned and pulled back out to sea, and rowed all the way around to the other side of Depoe Bay to Whale Cove, about three miles south, and came ashore there.

By the time they got to land, it was almost dusk, and Frank Tiffney was beyond help. He succumbed to hypothermia shortly after they reached the shore.

There were plenty of locals eager to help the sailors out, but unfortunately all of them were three miles to the north clustered around the burning ship. In Whale Cove, the sailors found there was nobody there to help them. They cast about a bit looking for shelter; but they ended up huddling on the beach around a fitful campfire trying to stay warm as darkness fell.

In the morning they hiked out in various directions to find settlements where they could get help.

In the end, it could certainly have been worse; Tiffney was the only fatality. But the crew definitely would have had a more pleasant shipwrecking experience if they’d pulled in at Fogarty Creek as they’d originally meant to do!

I mentioned that there are two large pieces of the J. Marhoffer still around and attracting visitors today. One, of course, is the big duct pipe stuck in the bluff overlooking the bay. The other piece is the firebox of the ship’s boiler.

This firebox is quite large, about 12 feet long and probably 10 feet wide, shaped like a giant soup can. When the boiler exploded and blew the ship to pieces, the firebox never left the blast site; it’s nestled among the rocks at the base of the bluff and is usually covered by the sea. But at very low tides, when the conditions are right, it can be reached via a rough trail leading down from Highway 101, from that parking area I mentioned at the start of this story.

It’s because of that rusty firebox — still mostly intact despite more than a century of immersion in salt water — that the little bay where the Marhoffer fetched up, formerly known as Briggs Landing, is today called Boiler Bay.

(Sources: “The Remains to be Seen,” an article by Niki Hale Price published Jan. 14, 2009, in Oregon Coast Today; “Boiler Bay and the J. Marhoffer Shipwreck,” an article by Andre Hagestedt published Dec. 13, 2018, in Oregon Coast Beach Connection; “Shipwrecked boiler a hidden treasure on the Oregon coast,” an article by Jamie Hale published July 22, 2018 in the Portland Oregonian)

Finn J.D. John’s most recent book, “Bad Ideas and Horrible People of Old Oregon,” was published by Ouragan House early this year. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.

Comments