A stiff shot of history

In other words, he never had a snort down at the saloon.

He remained a beloved figure until 1856, when he encountered another beloved figure, Andrew Jackson Masters, and shot him in the face.

Historian Ken Bilderback brings up the incident to illustrate the yin-yang morality of Oregon in the Old West, especially as it relates to the demon rum. “Here was a guy who was so pious about alcohol, but murder? Meh.”

Bilderback takes a look at 19th century Oregon history through the lens of a whiskey bottle when he presents a program called “Wine and Whiskey in the Old West” at 6:30 p.m. Monday, Jan. 29, at Hotel Oregon, 310 N.E. Evans St. Sponsored by McMenamins and Linfield College, the program is part of Hotel Oregon’s History Pub series.

Be careful, Bilderback said. Like purveyors of alcohol in the Old West, he is luring people in with rot-gut whiskey when he really has something else in mind. “They asked me to talk on social justice, so I’m fooling people,” he said. “I’m talking about wine and whiskey, but what I am really talking about is race, gender and social justice.”

Prohibition was enshrined, albeit temporarily, in the Constitution through the 18th Amendment in 1920, but laws forbidding the sale and consumption of alcohol had been enacted or debated for generations. Such laws were often used as weapons against women and ethnic minorities, Bilderback said.

Men opposed to women’s suffrage often used prohibition as an argument. If women got the right to vote, they said, the first thing they would do with their newfound political will is deprive a man of his God-given right to get drunker than a boiled owl. Harvey Scott, the influential editor of The Oregonian from 1866 to 1872, used this argument even though his sister, Abigail Scott Duniway, was one of the most prominent suffrage leaders in the country and refused to connect prohibition to voting rights.

The irony was that Harvey Scott advocated prohibition himself. Bilderback said Scott nonetheless cynically played on men’s fears to fight the suffrage movement. “Scott was a bitter foe of nearly all of the causes championed by women, and vehemently opposed suffrage,” he said.

Many women crusaded for prohibition because men who abused their wives and children were often alcoholics —”dipsomaniacs,” as they were called at the time. However, women also championed many other causes, including child-labor laws, public high schools and the abolition of the death penalty.

“Duniway pleaded with others in the suffrage movement to not allow the temperance movement to dominate the women’s movement because men would not grant the right to vote if it meant prohibition,” Bilderback said.

Of course, it should be noted, Oregon women were granted the right to vote in 1912, and two years later in the first statewide election in which women could vote, the death penalty was abolished and the sale of alcohol was banned.

Bilderback said racism played a major role in early laws against alcohol. “Race and alcohol really are the topics that define Oregon history,” he said. “Particularly race. Alcohol really had race at its core.”

The Oregon Territory was founded by two seemingly disparate groups, New England missionaries and Ozark and Appalachian mountain men, he explained.

“Race was easy to resolve, because both sides wanted to disenfranchise indigenous people and exclude blacks and Asians,” he said. “Alcohol appeared to be a major stumbling block, but it really wasn’t. Both sides wanted to keep liquor out of the hands of indigenous people and people of color, so banning over-the-counter alcohol was not particularly controversial.”

Moonshine stills were common at the time, and physicians and pharmacists often prescribed alcohol and opiates for almost any affliction.

When the Oregon Territory banned alcohol in the 1840s, “missionaries and mountain men were happy, but the merchants, mariners and mayors in Portland and other port cities were not,” Bilderback said.

“Early Oregonians hated paying taxes, but thirsty sailors didn’t as long as they could buy a drink. Soon, selling alcohol was legal again, and Portland resumed raking in liquor tax — its primary source of revenue for years.”

Other cities remained stubbornly dry. Forest Grove was one of them and missed out on saloon taxes. However, the town became nationally famous for being dry. In 1880, Forest Grove became one of the first cities on the West Coast to be visited by a sitting president, the teetotaling Rutherford B. Hayes.

Newberg, Forest Grove and Monmouth were among the few cities to pass up the opportunity to collect liquor taxes. Those cities’ prohibitionist tendencies helped spur the creation of Cornelius, Independence and Gaston, which welcomed saloons, said Bilderback. “By 1900, Oregon was booze-soaked, as was the rest of the country, and a national movement began to ban alcohol,” he said.

The call for all-out prohibition was motivated in part by the dangers of unregulated alcohol. Back in 19th century, there were almost no regulations on anything, including workplace safety, immigration, medicine or alcohol.

“Among other things, that meant that people could sell beer, wine and whiskey made from almost anything,” Bilderback said. “That resulted in people going blind or dying from tainted booze. It also meant that most medicines, including those for babies, contained alcohol or opiates without any requirement to reveal trifling things such as concentration.”

There were no age restrictions in saloons, and people could drink until they died.

The first half of Oregon’s history was marked by a “deep distrust of local law enforcement, which often was incompetent, corrupt or both,” Bilderback said.

Sheriffs were often unpaid. They made their money on fines. There was no incentive to solve murder cases, so many murders were written off as suicides. Farmers and ranchers put their trust in the federal government, which enforced laws more fairly and uniformly.

Although Oregon’s prohibition laws targeted minorities and were rarely enforced against white people, Bilderback said, that started to shift in the 1920s with the passage of the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act, which allowed federal agents to enforce laws on alcohol.

Of course, national prohibition didn’t turn out as well as everyone hoped. “Far from ending crime, as its supporters had hoped, it created a new breed of criminals and added to the public’s strong distrust of law enforcement,” he said. “You can’t talk about organized crime without talking about prohibition.”

Since the end of national prohibition in 1933, there has been no widespread effort to ban alcohol, although some Oregon cities remained dry for decades. Monmouth was the last holdout. Alcohol became legal in the community in 2002.

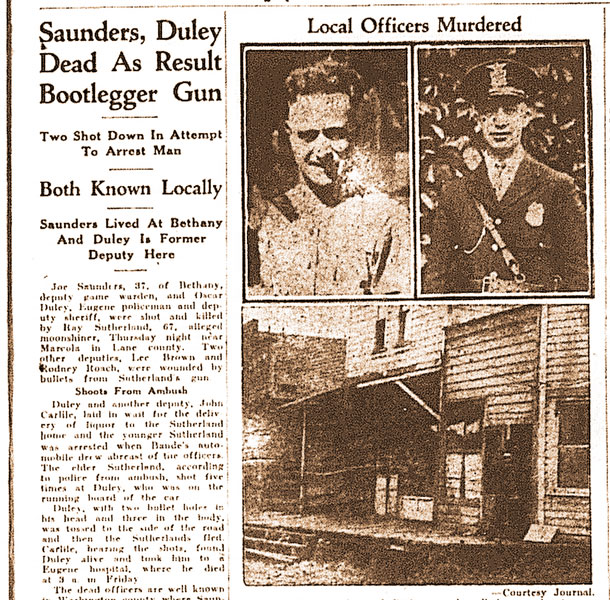

Bilderback promises a rousing presentation next week. “I’ll talk about a bootlegging sheriff, and an eccentric automotive pioneer’s wild parties in the hills,” he said. “I’ll talk about how contempt for law enforcement in early Oregon turned moonshiners into cult heroes, including one who killed two deputies. I’ll talk about government corruption, declaration of martial law.”

All the stories come from the books “Walking to Forest Grove” and “Law and Order at the End of the Oregon Trail,” which he wrote with his wife, Kris.

While Kris Bilderback won’t be on stage, her husband said she is the unseen force behind all the history presentations he delivers around the area. She researches and edits and spends thousands of hours going through microfilm, Bilderback said. She works for the Oregon Medical Association, but most of her career was in college administration at the University of Washington, Bastyr University and Pacific University.

Bilderback worked for 25 years as the news editor of The Columbian in Vancouver. He also worked for Newsday in New York. After leaving The Columbian, the lifelong city dweller and his wife bought a farm in Gaston in 2004 and began raising chickens.

Farm's history sparked book ideas

The Bilderbacks do a lot of their research by combing through old newspapers. “Probably because I am a newspaper guy, we use newspaper archives as much as anything else,” he said.

There is an emotional element to newspaper accounts, especially old ones, that gets lost in history texts. “The language was extremely raw,” he said.

The newspapers also include the casual racism of the age that otherwise tends to get glossed over. “I think that makes it all the more important to address,” he said.

Although he frequently gives presentations, Bilderback said he is painfully shy. It takes all he has to get up before an audience, but he usually becomes energized once he gets started. Still, he said, he doesn’t like the attention of being on stage. “I almost want to be anonymous and let the stories tell themselves.”

The stories are usually tales of ordinary people, but they contain themes that speak to larger issues. “We share little things, but we tell big stories,” he said.

The couple spends so much time thinking about the past that people sometimes make the mistake of thinking they are uncomfortable in the 21st century. Bilderback admitted he likes some of the aesthetics of days gone by, but he is glad he lives in the present.

“People ask, if I had a time machine, what era would I like to visit? I say tomorrow.”

More history coming to pass

History Pub presentations are held at 6:30 p.m. the last Monday of each month at McMenamins Hotel Oregon, 310 N.E. Evans St., McMinnville.

Historian Ken Bilderback will discuss alcohol’s role in 19th-century Oregon during his program, “Wine and Whiskey in the Old West,” on Monday, Jan. 29.

History Pub continues Monday, Feb. 26, with “Whaling the Pacific World: An Unprecedented Adventure” by Lissa Wadewitz, associate professor of history at Linfield College.

On Monday, March 26, Oregon Encyclopedia author Jim Scheppke will present “The Making of ‘The General’: Buster Keaton’s Masterpiece.” A screening of the film will be followed by a question-and-answer session.

Local History Pub presentations are sponsored by McMenamins and Linfield College. For more information, call Hotel Oregon at 971-267-3251.

Farm's history sparked book ideas

When Ken and Kris Bilderback bought their farm near Gaston in 2004, Ken noticed on the title that it was listed as waterfront property.

However, there was no waterfront to be found. He saw some blackberry brambles. Turned out, a seasonal creek passed through their land. “In the winter, it’s roaring,” he said. He found that it fed into Wapato Lake, which no longer exists.

“I had an idea for a book about this creek with no name running flowing into the lake that doesn’t exist,” he said.

While he was researching the book, a neighbor talked to him about the murders on the property. Margo Compton, 24, was found dead in her Gaston home in 1977. Her daughters, Sylvia and Sandra, were also murdered, along with her 19-year-old boyfriend, Gary Seslar. Each of them had been shot in the head.

Hell’s Angels leader Robert G. McClure, 47, was sentenced to four consecutive life terms in 1994 for the murders. Prosecutors argued McClure was ordered by Odis Garrett, ex-president of the Hell’s Angels in Vallejo, California, to kill Compton in retaliation for her testimony against several club members in a San Francisco prostitution trial.

Bilderback can still see the slab on his property where Compton’s house once stood.

This macabre bit of history led the couple to write four books, each exploring small but revealing stories about Oregon history: “Creek With No Name,” “Fire in a Small Town,” “Walking to Forest Grove” and “Law and Order at the End of the Oregon Trail.”

“I’ve always been a huge history buff, but I don’t think of myself as an historian because there is no accreditation or anything like that,” Bilderback said. “I think of myself as a storyteller.

“People criticizing our books say they read more like novels than history books. That’s true. I read boring history books, but most people don’t.”

Comments