Offbeat Oregon: Bing cherries are a product of the Oregon Trail

When cherry season rolls around, there’s never much doubt about what varieties you’ll find in your local grocery store. They’ll usually have some white or blush cherries, typically Royal Ann or Rainier; but most of them will be Bings.

Among cherry fans, the deep-red Bing is the gold standard, and has been for well over 100 years now. Rich and sweet, almost like chocolate in its intensity of flavor, the Bing dominates the supermarket and is most people’s favorite variety.

And there is probably no single fruit that’s more closely associated with the state of Oregon than this heavenly cherry, the ancestors of which actually crossed the Oregon Trail and may have saved its fellow travelers on the wagon train from harm at the hands of some fed-up Native tribes along the way.

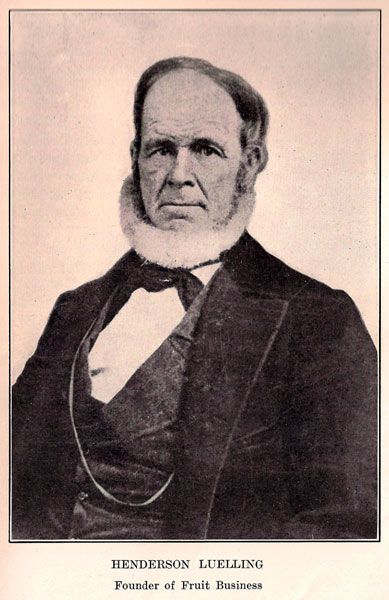

For all of that, we mostly have three fruit-growing brothers to thank: Henderson Luelling, and his younger brothers John and Seth (Seth preferred the original Welsh spelling of the family name, Lewelling).

The Luelling family was from North Carolina originally, and they moved in the 1820s to Indiana. They were devout Quakers and hardcore Abolitionists, which was likely at least part of why they left the Carolinas.

Henderson, the oldest brother, started a fruit-tree nursery in Indiana with brother John. They moved their operation to Salem, Iowa, in 1837.

By that time, Henderson had married a woman named Jane Elizabeth Presnall. The two of them, in the early 1840s, built a really nice stone house with two secret rooms in the basement, which they used to stow away runaway slaves as part of the Underground Railroad. In fact, Henderson and Elizabeth were so serious about the abolition of slavery that they were read out of meeting (basically, excommunicated) from the Salem Meeting of Friends. Most likely, the other Quakers in the meetinghouse thought their Abolitionist activities were too militant to square with the Quakers’ mandate to work for peace.

The Luellings responded by founding a new Quaker meetinghouse in Salem, the Abolition Meeting of Friends, and carrying on.

By the early 1840s, the Oregon Trail was starting to open up. Henderson had been obsessed with Oregon since several years earlier when he had found and read the memoirs of Lewis and Clark. A nasty winter that killed a bunch of his nursery stock was apparently the final straw for him, and he started gearing up to make the journey.

Luelling had no intention of just showing up in Oregon and hoping for the best. He was a nurseryman, and he figured if he expected trees to be there in Oregon for him to go back into business with, he was going to have to bring them himself.

To this end, he partnered with a neighbor and fellow nurseryman, William Meek. The plan was, the two of them would both head for Oregon in separate wagon trains, both of them bringing trees for the nursery they intended to establish there. Luelling would leave first, and Meek the following year.

For the journey, Luelling built a special heavy wagon with room for about 700 slips, cuttings, and saplings, and filled it with soil mixed with charcoal. He crammed as many trees into it as he could.

The tree wagon was in the vanguard when the Luelling family hit the road in 1847. By this time, Henderson and Elizabeth had eight children, with one more on the way. They traveled with two other Quaker families, presumably drawn from the Abolitionist meetinghouse they helped found: The Hockettes and the Fishers.

Along the way, they tried to travel with other emigrants, but friction developed because of the trees. The tree wagon was extraordinarily heavy, and hence slow. It also had to be watered at every possible stop along the way. Also, it attracted noticeable attention from Native Americans, which made everyone very nervous. So the other emigrants forged ahead.

This was likely a mistake on their part. Luelling was later told that many Native Americans saw trees as sacred, and considered that a wagon train carrying trees over the mountains was under the protection of the Great Spirit.

Whether for this or other reasons, not only did the Luellings have no “Indian trouble,” but when Elizabeth went into labor during the Columbia River part of the journey, Indian friends were happy to load her into a canoe and paddle her to The Dalles for medical attention. She gave birth to the family’s ninth child — a boy named Oregon Columbia Luelling — on the way there. (Oregon Columbia, by the way, went by “O.C.” his whole life.)

Then the powerful and dangerous Columbia Cascades had to be shot — trees and all. Again, their new Indian canoeist friends helped, retrieving a runaway flatboat that had missed the take-out point and was headed into more danger.

By the time Henderson and Elizabeth got to their destination in Milwaukie, they had lost only half their trees. But they’d gained a child and a large cohort of Native friends along the way. They also gained the opportunity to start what would become one of Oregon’s most important industries. Henderson Luelling today is most well known as the “father of the Oregon nursery industry.”

He’s also somewhat famous, or notorious perhaps, for an episode much later in his life when he tried to found a free-love cult in Honduras. But that, as podcast host Marcus Axford of the Welcome to Oregon podcast likes to say, is a story for another day.

In Oregon, Henderson and Elizabeth settled in Milwaukie and set up their nursery. They soon found that, in Oregon at least, money really did grow on trees. Newly arrived settlers, most of whom had not tasted fresh fruit in months, would pay plenty for a box of apples or plums.

When Henderson’s brother Seth arrived on the trail with brother John, he joined the family operation and basically took over the Milwaukie operations while Henderson traveled south to establish a nursery and orchards in the fast-growing San Francisco Bay area — by this time, of course, the Gold Rush had started. This would become the Oakland suburb of Fruitvale.

It is primarily Seth who we have to thank for the Bing cherry. Seth first cultivated a rich, deep black cultivar that he named the Black Republican. (This, by the way, is one of the most popular varieties used in high-end black cherry ice creams.) Seth, who shared Henderson’s enthusiasm for Abolition, named the cherry after the slur he often heard from pro-slavery neighbors wishing to insult him. He joked that he was going to make them relish a Black Republican whether they wanted to or not, and yeah, that probably worked! For what it’s worth, it’s my personal favorite kind of cherry.

Seth then crossed the Black Republican with the Royal Ann cultivar to create the famous Bing, which he named after his orchard foreman, Ah Bing.

(Ah Bing, by the way, deserves to be better known. How much he had to do with the development of the Bing is unknown, but it was probably significant. Unfortunately, after spending most of his life in Oregon cultivating the state’s best fruit, he made the mistake of traveling back to the Old Country to visit family, and was blocked from returning home to Oregon by the Chinese Exclusion Act.)

Besides the cherries, Seth and John developed the Golden Prune, the Sweet Alice apple, some improved rhubarbs and grapes, and a number of other fruits bearing the family name.

Other later events hinged on the Luellings’ success as well. Fellow Quaker John Minthorn’s Oregon Land Company, 40 years later, made a specialty of developing orchards to sell — a business plan obviously dependent on the tradition the Luellings imported. Without the Oregon Land Company, Minthorn’s teenage nephew, Herbert Hoover, would likely not have gotten the early training in sound business practices that was to be so important in his early career as an engineer. Hoover, of course, would go on to become the greatest enemy of the Third Horseman of the Apocalypse (famine) in the history of the world, with the possible exception of “Green Revolution” architect Norman Borlaug. But that, again, is a story for another day.

By the way, the story of the Luellings’ journey is the basis for Deborah Hopkinson’s children’s book, “Apples to Oregon,” one of the Oregon Reads book selections for the 2009 Oregon sesquicentennial celebration. The book springboards off the story to generate a “tall tale” about the journey with the tree wagon.

(Sources: “The Blacker the Cherry: The abolitionist history of the Black Republican Cherry,” a story by Tyler Boudreaux aired by Los Angeles National Public Radio Station KCRW on June 20, 2022; History of Oregon, a book by Charles Carey published in 1922 by Pioneer Publishing)

Finn J.D. John’s most recent book, “Bad Ideas and Horrible People of Old Oregon” was published by Ouragan House early this year. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.

Comments