Offbeat Oregon: Most famous Silverton resident wasn’t Clark Gable; it was a dog

Up until his untimely death from a fall in 1937, Rogue River Wilderness mountaineer and mule-train driver Hathaway Jones enjoyed a reputation as the “damnedest liar” in all the West Coast states and probably a couple dozen inland ones too.

And he was proud of that reputation. When the Portland Morning Oregonian referred to another backwoods character as the “biggest liar in the country,” Hathaway claimed he was going to sue the paper for defamation.

(As a side note, that competitor for the “biggest liar” title was probably Ben Finn of Finn Rock, who at one point actually bamboozled the editor’s own sister with a tall tale. So it’s easy to see how they could make such a mistake.)

Even today, folklorists brighten a little at the mention of Hathaway Jones’ name and, if you don’t change the subject quick, you’ll be stuck listening to them recite their favorite Hathaway Jones story.

Arthur Dorn was one such folklorist, and he is the one who assembled the largest collection of Hathaway’s tall tales and published it in 1941. Like all of them, he had a favorite story. He got it direct from Hathaway Jones himself, while chatting him up at the Agness boat landing in 1925. It’s a story about two of Hathaway’s favorite hunting hounds, Towser and Nellie.

Hathaway told Dorn that a safari sportsman from Virginia had hired him to pack himself and his ten hunting dogs into grizzly country to bag a bear. This was, of course, back when grizzlies still were to be found in the Craggies (the leftover bits of old Mount Mazama between Gold Beach and Grants Pass, which are some of the most remote bits of Oregon still today).

Hathaway never gave the Virginia man’s name, but in a nod to Jean Knight, let’s call him Mr. Big Stuff. Mr. Big Stuff was one of those rich fellows who used to make a hobby of wandering around the world shooting large and exciting animals (do people still do that? Let’s hope not).

Here is the story, as Hathaway tells it:

Upon arrival, Mr. Big Stuff assumed that his dogs, which had already contributed numerous dead lions and tigers and Cape buffaloes and such to his taxidermy collection, would be more than a match for any decadent, overfed Southern Oregon bear. But, following some bear-hunting misadventures born of that overconfidence, Mr. Big Stuff found himself dogless, so he offered Hathaway $1,000 for his two prized hunting hounds, Towser and Nellie.

A thousand bucks was about two years’ income for Hathaway, so reluctantly he agreed, and sent Towser and Nellie off to the East Coast with Mr. Big Stuff.

A month later, Hathaway got a letter from Virginia. It seemed Mr. Big Stuff was having a very hard time. On the way back east, Towser and Nellie had bitten everyone they could reach and when they couldn’t, they howled and screamed out eldritch noises that raised the hair on the back of everyone’s neck. When they finally reached Virginia, they were put in a corral with an eight-foot fence; they promptly jumped the fence and went on the lam. Mr. Big Stuff had not seen them since.

Two years passed, and then one dark night Hathaway was sitting around alone in his cabin thinking of Towser and Nellie and wishing he hadn’t sold them, when he heard Towser’s distinctive howl. It was followed by Nellie’s, and then a chorus of lesser, more youthful howls.

Soon the cabin was invaded by a large pack of dogs, or rather mostly-grown-up puppies, with Towser and Nellie at the lead. The puppies, six of them, stood at attention while Towser and Nellie had their joyful reunion with Hathaway; then they introduced their new family, which they had raised on the road while journeying across the continental United States from coastal Virginia back home to the Rogue River country.

“This was the pack of hounds that made Hathaway the most famous hunting guide on the Rogue,” writes folklorist Stephen Dow Beckham in his book.

The most interesting thing about this tall tale, arguably, is that we know its source, or at any rate we can guess it with some confidence. The year before Hathaway Jones told this story to Arthur Dorn in his famously earnest deadpan way, something kind of similar happened in the town of Silverton, and it made national news. Hathaway, who spent the last 40 years of his life carrying the mail to Rogue Valley residents, would definitely have known all about it. Probably Dorn did too.

It was the story of Silverton’s Bobbie the Wonder Dog, a Scotch collie dog who tracked his owners more than 2,500 miles back home from Indiana after he got lost during a family vacation. And unlike Hathaway Jones’s doggie-Bonnie-and-Clyde yarn, the story of Silverton Bobbie is absolutely and provably true.

Bobbie the Wonder Dog, a.k.a. Silverton Bobbie, is still today Silverton’s most famous celebrity. And that’s saying something; the town has been home to some very notable personalities, including Clark Gable and political-cartoon legend Homer Davenport.

This picturesque little town nestled right between the east side of the Willamette and the west flank of the Cascade foothills, about 15 miles out of Salem, has gotten a lot busier in the last decade or two as visitors to Silver Falls State Park and the Oregon Gardens have noticed its particular small-town charms.

But back in 1923, it was basically a quiet little timber-and-sawmill town.

The lumber mills and timber operations furnished Silverton with hordes of hungry young men looking for reasonable dining options all the time, so one of the best businesses to have in Silverton — other than a sawmill, of course — was a cork-boot café. (A cork-boot café, for the uninitiated, is a diner that caters to loggers with huge, cheap meals, and has a “NO CORKS” sign on the door to remind the boys to take their caulked boots off before entering.)

One of the most popular cork-boot cafés in Silverton was the Reo Lunch Restaurant, owned by Frank and Elizabeth Brazier. The Reo did plenty of business, enough for the Braziers to own a pretty nice car — a brand-new 1923 Willys-Overland 92, one of a new series of mid-market autos marketed as “the bird cars.” Depending on the color of your Model 92, it was a “Blue Bird,” a “Black Bird,” or a “Red Bird.” The Braziers’ was a Red Bird.

After they bought the car, the Braziers packed the family into it — daughters Leona and Nova, and of course Bobbie — and headed east for a family-vacation summer road trip. The destination was Wolcott, Indiana, where some other family members lived.

This, of course, was a much more involved process than it became a few years later. Cars in 1923, even brand-new really nice ones like the Red Bird, were not very reliable, and road conditions could be awful. They also required a lot of maintenance along the way.

So as the family headed out from Silverton in an easterly direction, with Bobbie perched proudly atop the luggage in the back or riding jauntily on a running board, the plan was to stop well before dark each night in a town big enough to have a mechanic’s garage and service station, where they could park the car under cover for the night — like putting up the buggy and team at the livery stable in an earlier day. Then the family would walk to a nearby hotel for the night.

Well, the travelers were almost to their destination in Indiana, about 2,300 miles into their road trip, when it happened: Frank was gassing up the Red Bird at a service station when a pack of local mongrels spotted Bobbie and jumped him. The last Frank saw of Bobbie that day, he was running at top speed with three snarling dogs in hot pursuit.

Frank wasn’t too worried at the time. Bobbie, he figured, could take care of himself; most likely he and the Indiana dogs would have a little tussle, become best friends, and spend the rest of the afternoon playing and chasing cats. He figured Bobbie would be back at the hotel where the Braziers were staying later that night.

Only, he wasn’t.

The Braziers took an extra day or two to search for Bobbie. They called around town, advertised in the local newspaper, and drove around hollering for him. Still no Bobbie.

So, leaving instructions to hang on to him if he reappeared, they continued on their trip. They’d pick him up on the way back home, they figured.

They figured wrong, though. Bobbie still wasn’t around when they came back through. So, regretfully, the Braziers continued on their way, leaving instructions to send him home on a rail car at their expense if he should turn up.

This has to have cast a pretty awful pall over the rest of the Braziers’ road trip. Anyone who has ever had a beloved pet disappear knows that feeling: hoping for the best, but fearing the worst.

And, a week or two later, the Brazier family was back home, helping cook stacks of hotcakes and slabs of beefsteak for hungry loggers and millworkers in the Reo Lunch.

Exactly six months later, daughter Nova (whose last name was Baumgarten; she was Elizabeth’s daughter from a previous marriage) was walking down a Silverton street with a friend when she suddenly seized the other girl by the arm. “Oh look!” she cried. “Isn’t that Bobbie?”

Sure enough, it was Bobbie — sore of foot, matted of coat, badly underweight, his toenails worn down to the quick.

Bobbie had spent half a year walking (or dogtrotting, as it were) the 2,300 miles from Indiana to Silverton. Actually, if he’d had a way to count, his true mileage was probably closer to 3,500 miles, counting the time he spent casting around for the Braziers’s scent and picking up their trail along the way. He’d crossed the Continental Divide in the dead of winter, and he’d had to swim rivers and run from dogcatchers in at least eight different states on his westward journey.

Nova, of course, brought Bobbie to the Reo for a joyful reunion with her sister, mother and stepfather. He was promptly furnished with a luxurious meal of sirloin steak and whipping cream.

This happened during the lunch rush, and the place was packed with mill workers (possibly including Clark Gable, who had not yet been “discovered” and was working a shift in a local sawmill at the time). It was a matter of minutes before word of Bobbie’s amazing journey was on everyone’s lips, all over town.

Within a week or two, word had leaked out to the national press, probably through coverage in the Silverton Appeal-Tribune. Friendly people with whom Bobbie had stayed for a night or two on his journey started writing letters to tell their stories. Soon there was enough information for the Humane Society of Portland to piece together a surprisingly precise account of Bobbie’s journey.

After coming back to Wolcott and finding the Braziers gone, Bobbie first followed them northeast, farther into Indiana. Then he started striking out on what must have been exploratory journeys in various directions, probably trying to pick up a familiar scent to give him a sense of what direction he should take.

Eventually, he found what he was looking for, and struck out for the West Coast.

On the way back, Bobbie visited every one of the service-station-cum-livery-stables that the Braziers had garaged their car in on the way out. He also visited a number of private homes. Along the way, he spent some time in a hobo camp; and in Portland, he stayed for some time with an Irish woman, who nursed him back to health after some sort of accident left his legs and paws gashed up.

(As a side note, this injury may be the source of two of the more farfetched claims about Bobbie: one, that he actually rode the rails like a real human hobo, and one that his paw pads were “worn down to the bone” upon his return. Neither of these claims is in any of the 1924 newspaper articles I found, but several modern accounts throw them in.)

“Poor Bob was almost all in,” Frank Brazier said. “For three days he did little but eat and sleep. He would roll over on his back and hold up his pads, fixing us with his eyes to tell us how sore his feet were. His toe-nails were down to the quick, his eyes inflamed, his coat uneven and matted, and his whole bearing that of an animal which has been through a grilling experience. When he first came back he would eat little but raw meat, showing that he had depended for sustenance chiefly on his own catches of rabbits or prairie fowl.”

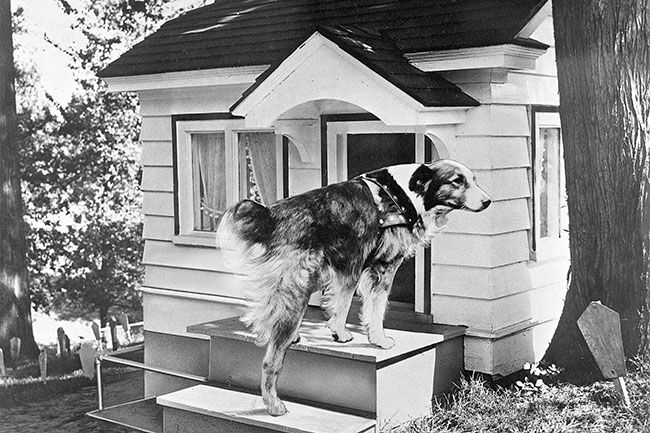

After the joyful reunion, Bobbie’s life stayed pretty exciting. The Humane Society gave him a medal in a sober ceremony in Portland. Silverton gave him the key to the city, along with special permission to walk its streets free of fear from the municipal dogcatcher. Correspondence poured in addressed to “Bobbie the Wonder Dog.” He was honored as the star of the Home Beautifying Exposition in Portland a few months after his return, and a miniature bungalow was built to serve as his doghouse.

For Bobbie, the best was yet to come. He was featured in the “Ripley’s Believe it or Not” comic strip and, last time I visited (although it’s been many years), his story was part of the exhibit at the Ripley’s Believe it or Not museum on the Newport bayfront. He became a movie star later in 1924, starring as himself in the silent film The Call of the West. And, of course, the Braziers made sure he never had to hunt for meals again!

Alas, Bobbie had not much time to enjoy these perks. He died in 1927 after falling ill. Veterinarians suggested it might have been the strain of his journey catching up with him; but this seems unlikely coming three symptom-free years later.

In any case, he was buried with maximum ceremony at the Humane Society’s pet cemetery in Portland, and Rin-Tin-Tin — the first movie-star dog of that name — was coached to lay a wreath on his grave.

In the years since, Bobbie’s story has only gotten bigger. It was the inspiration for the Silverton Kiwanis Club’s annual Pet Parade, which has happened every May since 1932. Numerous children’s books, and grown-up books too, have been published to tell his story.

And, of course, Bobbie has been an inspiration for plenty of tellers of tall tales such as Hathaway Jones ... but they’ve really had to bring their “A game” to come up with a lie that’s a bigger whopper than the real thing. I would argue that no one has yet managed it — not even the great Hathaway Jones.

(Sources: Silverton’s Bobbie: His Amazing Journey, a book by Judith Kent published in 2004 by Beautiful America; Wonder Dog: The Story of Silverton Bobbie, a book by Susan Stelljes published in 2005 by For the Love of Dog Books; “Bobbie the Wonder Dog,” a column by Alan E. Hunter published April 28, 2018 at alanehunter.com; Tall Tales from Rogue River, a book by Stephen Dow Beckham published in 1974 by IUP; archives of the Silverton Appeal-Tribune and Portland Morning Oregonian, February and March 1924)

Finn J.D. John’s most recent book, “Bad Ideas and Horrible People of Old Oregon,” was published by Ouragan House early this year. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.

Comments

Bouncer

HUMAN BEING/DOG