Jim Moore: Midterm elections Where we went, where we might go

It was an election of high turnout. It was also an election of hard-fought statewide races that solidified Oregon’s identity as a Democratic state, with Republicans steadfast in challenging the prevailing ideology. It is in this context that state governance will transpire in 2019.

Voter turnout in Oregon is a funny thing.

We pride ourselves on our national top-5 voter participation rate, but we only count the percentage of registered voters while the rest of the country generally counts the percentage of voting age population. So while Oregon residents and officials brag about an 80 percent turnout in a presidential election, the actual figure is about 65 percent.

Like the rest of the country, Oregon generally has higher turnouts during presidential election years. This off-year election turned that on its head, however, as more than 1.9 million turned out.

That’s about 373,000 more than the off-year election in 2014 and 123,000 more than the presidential election of 2012. Turnout in our recent election trails only the record 2.05 million of the 2016 presidential election.

The hundreds of thousands of Oregonians automatically registered through the Division of Motor Vehicles actually voted.

Data from the past three off-year elections reflects a 19 percent increase in voter participation. That means a larger swath of Oregonians are engaging in determining the political direction of our state.

The biggest race, by far, was the gubernatorial contest between Kate Brown and Knute Buehler, who raised a combined $39 million in campaign funds.

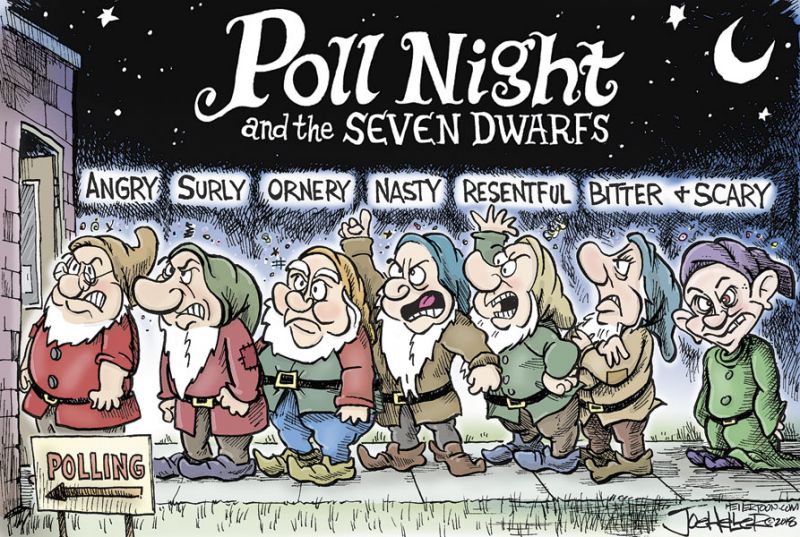

While neither candidate did a very good job of explaining the policies they would pursue if elected, the narrative that developed early on incorrectly forecast a close election. That was fed in part by local and national media that felt somewhat burned by the discrepancy between polling and actual voting in the 2016 presidential race.

Brown ended up winning by a convincing 6.4 percent. So how did the narrative of a down-to-the-wire race go wrong?

First, most polling showed consistent 4 to 5 percent leads for Brown. This meant, given the margin of error, that Buehler had a relatively narrow path to victory and Brown a much broader one.

Polls that had it much closer significantly over- or under-sampled elements of the electorate. One widely-cited poll featured about 35 percent unaffiliated voters — an element that usually runs only about 20 percent.

Second, Buehler had to keep all his fellow Republicans together — usually about 32 percent of voters — as well as gain the vast majority of unaffiliated voters — usually about 20 percent. He needed about 75 percent of all unaffiliated voters to support him.

As a result, his message became complex. He appealed to Trump supporters with his stance to repeal Oregon’s sanctuary status and unaffiliated and Democratic voters with assertions of moderation on social issues.

That’s one tough coalition to create and maintain.

Given a historic Democratic voter share of about 43 percent, Brown only needed about 25 percent of the unaffiliateds to win. It was not up to her to move the electorate; it was up to Buehler.

Third, in examining gubernatorial elections over the course of Oregon history, Republicans tend to win by a lot — average victory margin, 17.4 percent — and Democrats by only a little — average victory margin, 7.0 percent. All those polls showing margins of 4 to 5 percent were predicting exactly what we would expect from a Democratic candidate.

The ballot measures were all hard-fought in their own way. But final results reflected the Democratic Party’s bloc message of No on 103, 104, 105 and 106, which proved surprisingly effective.

In fact, results for 104 through 106 were virtually identical, suggesting the Democratic message on them drew much wider support than that of the party’s statewide candidates. That’s something ballot measure sponsors will need to remember in 2020.

For fifty-seven of the sixty House seats, the projected winner prevailed. All three upsets were pulled off by Democrats, two challenging Republican incumbents and one seeking an open seat.

There were 15 Senate seats up this year. Democrats were expecting tough races in Southern Oregon and Washington County, but managed to turn them into easy wins.

Now the Democrats have firmer control in both the House and Senate, rewarding them with unilateral tax-raising capability in both chambers, assuming party discipline holds.

The governor is in her second term, which past governors have been inclined to take more chances and promote more big ideas in areas such as land use, tax reform and health care. However, her party’s narrow supermajority in the Senate — right on the three-fifths line — means any one of its members can block tax plans or use the resulting leverage to incorporate a broader array of revenue ideas from a broader range of legislators.

Oregon faces critical issues in the coming years. Chief among them is the structural deficit driven by the obligations for health care and public employee retirement, compounded by a state income that does not meet those obligations.

Some balance of cutting programs and raising revenue is clearly in the future, as it has been in the past. All other issues — carbon cap and trade, improvements in the delivery and accountability of state services and a host of others — are secondary.

Despite the Democratic stronghold, no state policy will have a true grounding in political legitimacy if it does not draw some measure of Republican support, as 40 percent of Oregonians are represented by GOP senators and 37 percent by Republican representatives. These significant portions of the electorate deserve a voice at the table, contingent on their willingness to make their opinions heard to their elected representatives.

For citizens and officials alike, it means doing homework to better understand issues. Partisan stances may feel good, but they are not often grounded in the hard reality of creating policies that work.

Comments