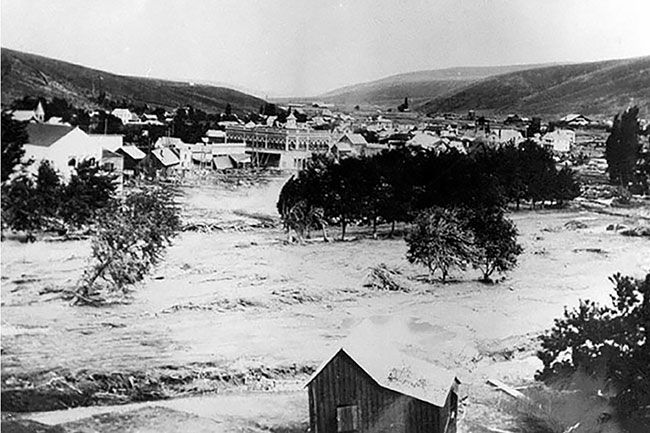

Offbeat Oregon: The country’s deadliest natural flash flood happened in Heppner

On June 15, 1903, a strange little article appeared in the Portland Morning Oregonian.

“It is reported that a tremendous cloudburst occurred at Heppner late in the afternoon,” the article states. “All communication with that town has been cut off and nothing definite can be learned.”

The silence must have struck the editors as ominous. Heppner was a modern 20th-century town, with a telegraph office and a telephone exchange. Also, by press time they would have at least heard rumors that a massive, unsanitary slug of muddy water clotted with farm animals, household goods, and other domestic debris had just gushed downhill through the towns of Lexington and Ione following the banks of the usually-tiny Willow Creek, doing considerable property damage. Lexington and Ione were just downstream from Heppner.

It wouldn’t be until late Sunday night, well past the hour the Oregonian was on the presses, that the outside world would start to learn the full story:

At 5:20 p.m. on that sultry Sunday afternoon, a wall of muddy, turbulent water 30 to 40 feet high had slammed into the town, scooping up roughly a third of its buildings and killing 247 of Heppner’s 1,290 residents.

It was the worst flash-flood disaster in U.S. history with the sole exception of Pennsylvania’s Johnstown Flood, measured by loss of life. (The hurricane-driven flooding that struck North Carolina earlier this year, including the city of Asheville, killed 129, including 26 who are still missing). And it remains the deadliest disaster of any kind in the history of Oregon.

Heppner was one of the most important towns on the Umatilla Plateau — the grassy uplands that flank the Columbia River east of Rowena Crest, about 10 miles west of The Dalles — at the turn of the 20th century. Roads radiated out from Heppner like spokes on a wheel; it was centrally located in an excellent spot to service the timberlands of the Blue Mountains to the southeast as well as the lush pasture lands to the south and west. It was, and still is, the county seat of Morrow County.

The story of the Umatilla Plateau over the past century and a half is an interesting one. In the 1870s, the Umatilla Plateau was a grassland, thickly covered with the bunchgrass that was native to the region. Bunchgrass was a perennial plant with deep roots — it had to be to survive in an environment that got just 20 inches of rain each year, and most of that in sudden cloudbursts. Bunchgrass had evolved on the plateau to capture those sudden blasts of moisture before they could run off, letting it soak deep into the earth where it could be drawn on during the long dry months.

That made bunchgrass fabulous forage for livestock, and it wasn’t long before the Umatilla Plateau was basically the sheep capital of the West.

Most of the land was public, though, so there was no incentive not to overgraze it. As a result, a lot of the bunchgrass got chewed down to the roots. It wasn’t very fast-growing, so it tended to stay that way. Sometimes it was grazed so aggressively that whole hillsides just dried up and died.

Then someone figured out that wheat could be grown there most years (depending on rainfall), and large sections of the remaining bunchgrass got plowed up so that wheat could be planted there.

And that was fine for the most part. But all those bare dirt fields, bristling with tiny slips of growing wheat stalks, could not do what the bunchgrass did so well — capture water when a whole lot got dumped on them at once, and hold the soil so that it couldn’t wash away.

That was a problem, but nobody considered it a deal breaker. Folks hated to lose the topsoil when the cloudbursts happened, but they didn’t really understand yet how thin the topsoil layer was and how hard it would be to replace. Plus, most of the time, the rainstorms that hit the region were small.

But outside of its Native American communities, north-central Oregon was a very new community. Nobody who lived there had any idea how bad it could get ... until that sultry Sunday afternoon of June 14, 1903.

On that day, the residents of Heppner were sweltering. It was 94 degrees, and probably pretty humid, because there had been a small thunderstorm earlier in the week. The thunderstorm had broken a long dry spell and had brought a little moisture — but not enough to ensure the wheat crop survived. Everyone was hoping for a little more.

And it looked like they were going to get it. As the afternoon wore on, heavy clouds started forming in the hills south of town. Then, a little after 4:30 p.m., the skies started opening up, and the first drops of rain came down on the little town. Lightning flashed.

Half an hour later came hail — big rough chunks of ice plummeting out of the sky, clear ice lumps the size of chestnuts, big enough to really hurt when they hit you. Residents scurried inside to escape the pounding.

The hail continued hammering down on the town, making a tremendous racket. This had a lot to do with why the flood was so deadly — not only were almost all Heppner residents in their houses when it happened, but the thunderous rattle of the falling hailstones masked the roar of the wall of muddy water, trees, boards, cattle, sheep, and other flotsam when it arrived, a few minutes later, at their village.

As the residents peered out into the stormcloud-dimmed sky watching the lightning flashes, the water the storm had unleashed a few miles upstream from them was on the move. Later visitors were able to actually see the channels it carved in the newly-denuded hills as it poured down toward the town, and the boulders it ripped out of the ground.

Most of the water ended up in the headwaters of the Balm Fork of Willow Creek, but the main fork of Willow Creek got lots as well.

Balm Fork merges into the main stem of Willow Creek just upstream from Heppner. Most summers, the water there is ankle deep.

On this occasion, though, the water coming down Balm Fork was probably ten feet high if not more. As the water had run down the canyon, debris had clogged every fence and bridge across the creekbed and held back the flood for a second or two while more water poured in and piled up. By the time it reached Willow Creek the crest was an enormous slug of water just thundering down the mountain. Witnesses compared it to a barrel rolling down the hill, thick with flotsam and debris.

It hit Willow Creek with full force, gouging a brand-new cove in the opposite bank of the creek. The swirling delayed the flood more; more water rushed in. The slug of water got even bigger. Then it rolled into Heppner.

The first thing it met in Heppner was a new steam laundry built cantilevered over Willow Creek at the upstream end. This laundry was stout and well built, and it held the water dammed up for a few more seconds before giving way and releasing the water into the town.

By that time the wall of water was taller than the houses it was slamming into. Eyewitnesses gave estimates of between 30 and 50 feet.

A few people saw what was happening in time to do something. One heroic man jumped on his horse and set out hell-for-leather downstream through town, shouting a warning to the people in the houses: “Flood! Run to the hills! Flood! Run to the hills!”

It’s extremely unlikely this man, or these men (there may have been two), survived the flood, as the water would have chased them down before they could reach the city limits. Also, no one today knows who they were. But a number of survivors credit their shouted warning with saving their lives.

Those who did not hear or heed this warning were apt to find themselves being carried downstream inside their houses, crushed by collapsing timbers or drowned in filth. Among those who were caught in the torrent, survivors were few. One lucky family rode downstream in their submerged house, up to their necks in water, and were able to escape when it fetched up against another structure. But for the most part, those caught in the flood drowned or were crushed as their houses were carried away and broken apart by the awesome hydraulic force.

When the floodwaters came, about 200 people took refuge in the Palace Hotel — the Palace was built of stone and brick, and was solid enough to resist the waters. Among those were Leslie Matlock and Bruce Kelly. As soon as the waters receded, the two of them hurried to a livery stable for horses (luckily, it was on high ground) and took off at a gallop downstream, racing the floodwaters in an effort to warn the downstream towns of Lexington and Ione — the telegraph and telephone lines were, of course, out of service now.

They had to stop to cut their way through several fences, which slowed them down; and they got to Lexington a few minutes after the water did. Luckily, it wasn’t hailing in Lexington, so the residents heard the water coming and got out of the way.

They passed the crest on the way to Ione, though, and got the warning out.

Nobody in either downstream town was killed in the flood. But the floodwaters contaminated every well they flowed over, and caused an outbreak of typhoid fever that killed at least 18 more people over the following month or two.

When it was over, the survivors in Heppner had an awful job ahead of them. A quote from the Portland Oregonian, reprinted in DenOuden’s article in the Oregon Historical Quarterly, sums it up: “Scenes at Heppner are indescribable in their gruesomeness, their anguish, their awful desolation. No pen can exaggerate the horrors they present. Every heap of debris may contain a human forming decomposition. Many do reveal such spectacles when uncovered, and meantime Willow Creek, as if to mock the dead, has returned to a purling brooklet.”

Residents of nearby towns and cities flocked to Heppner with food and manpower as well as financial contributions. A kitty passed in Portland swelled up to such a large sum that the residents of Heppner asked them to keep part of it and set it aside for the next emergency.

But Heppner needed the help. It was a horrible recovery job, especially because babies and toddlers made up a significant proportion of the dead. You can imagine what it must have been like to be a survivor or a volunteer from a nearby town, approaching a collapsed wall of a demolished house, lifting it up and praying there’s not another dead baby underneath it.

Today, nearly a century and a quarter later, the debris is gone and the damage long since repaired or cleaned up. But you can still see the effects of the flood with a stroll through the Heppner cemetery, located on a hill above the town. On headstone after headstone you’ll find carved, with chilling insistence, the same date of death: June 14, 1903.

(Sources: Calamity: The Heppner Flood of 1903, a book by Joann Green Byrd published in 2009 by Univ. of Wash. Press; “Without a Second’s Warning,” an article by Bob DenOuden published in the Spring 2004 issue of Oregon Historical Quarterly; “1903 Heppner, Oregon Flood,” a 15-minute documentary video produced by “The History Guy” (Lance Geiger) and published on his YouTube channel on June 14, 2023, the 120-year anniversary of the flood.)

Finn J.D. John’s most recent book, “Bad Ideas and Horrible People of Old Oregon,” was published by Ouragan House last year. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.

Comments