Randy Stapilus: Kotek might emulate Harding in her effort to unify Oregon

Gov.-elect Tina Kotek has promised to visit Oregon communities to bring the state closer together.

Nearly a century ago, one of Oregon’s smallest communities was declared “the capital of the United States all day long,” as an honorific.

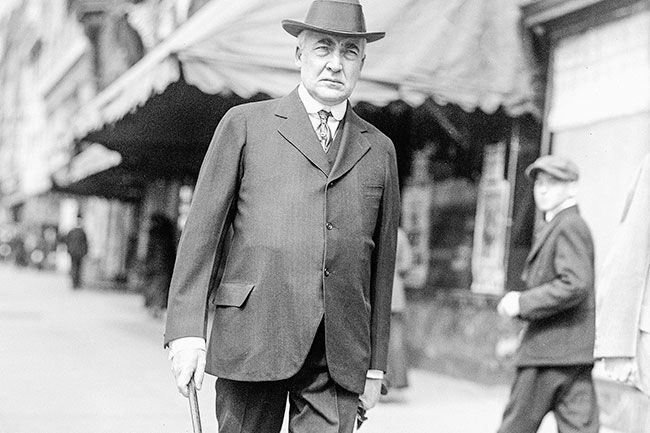

On that day, July 2, 1923, President Warren Harding, who was then on a transcontinental train ride — from which he wouldn’t return to Washington alive — stopped his train at the small Blue Mountains community of Meacham. Before rolling on west to Pendleton, he stayed there for eight hours and 20 minutes, spoke to a crowd and local officials, and made the highly informal declaration, no doubt delighting the assembled Oregonians.

The event did not transform Meacham, which today is a smaller community than it was a century ago. But it made a connection, and it brought people far from a metropolis together with the leadership of the nation. In its small way, it helped to unify.

Something like that is one part of what Kotek, winner of a three-way race in November, has promised to do once she takes office: bring together, at least to some greater degree, the many often splintered parts of Oregon. One way she could do that is follow Harding’s example — travel around the state and declare some far-flung communities Capital for a Day.

OK. It’s something of a gimmick and a stunt.

But taken seriously and handled with care, it could be more than that, especially if it became institutionalized and expected, the way the annual town hall gatherings of Sens. Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley have become. And there’s plenty of past experience to help Kotek do it properly.

Idaho’s governors, for one nearby example, have been holding capitals for a day around that widely scattered state for decades, though somewhat interrupted by the pandemic.

The governor’s website says, “Bringing members of the governor’s cabinet to a rural town in a different Idaho county every month, residents are able to address their issues directly with the governor and his administration for an entire day. Idahoans are encouraged to ask questions, share their opinions, and seek answers from state agencies.” And the events usually draw significant crowds.

Typically, they’re held in some of the smaller communities in the state, usually hours from the state capital of Boise. They have recently been held in Ammon, Rexburg, Troy, Driggs, Cascade, Parma, Glenns Ferry and Rathdrum — places that often don’t see a lot of statewide officials.

Idaho didn’t invent the idea. Governors around the nation have been employing capital for a day for decades as a way of bringing together state officials and a scattered constituency.

In July 2001, New York Gov. George Pataki signed a proclamation declaring Batavia “the official capital of New York.” Albeit just for a day, it generated a lot of conversation.

That was the first such occasion in that state, but it was followed by a string of others. And his successor, Andrew Cuomo, kept up the new tradition.

In 2008, Minnesota Gov. Tim Pawlenty declared a group of communities around that state as capitals for a day: Bemidji, Thief River Falls, Detroit Lakes, New Ulm and Winona.

In Florida, that state’s long-ago capital, St. Augustine, joined a long list of communities declared capital for a day in 2003. They each hosted a delegation of state officials.

In 2008, Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley launched a similar program, including such communities as Salisbury, Hagerstown, Ellicott City, Cumberland and Gaithersburg.

In Oregon, you could imagine the local impact – and impact on the state as a whole – if top state officials came face to face with the folks in places like Condon, Lakeview, Elkton, Cove, Willamina and Toledo, as well as a few that come a little closer to regional centers.

That would especially be true for those located in counties that have voted in favor of leaving Oregon and joining Idaho. With 241 cities in Oregon, there are plenty to choose from.

The positive impacts could be deeper, if less immediately spectacular, than President Harding’s long-ago stop at Meacham.

Guest writer Randy Stapilus is a former reporter and editor who has turned to writing and publishing books from Carlton. He has devoted his career to covering politics and government in Oregon, Washington and Idaho. In addition to publishing books for himself and others through the Ridenbaugh Press, he maintains a blog at www.ridenbaugh.com . In addition, he continues to write for print and online news publications, including the Salem-based Oregon Capital Chronicle, where this piece originally appeared. He can be reached at stapilus@ridenbaugh.com.

Comments