Boundary challenge denied, new districts affirmed

By JULIA SHUMWAY

Of the Oregon Capital Chronicle

Oregon’s new legislative boundaries are set for the next 10 years after the Oregon Supreme Court on Monday dismissed two challenges to the maps approved by legislative Democrats.

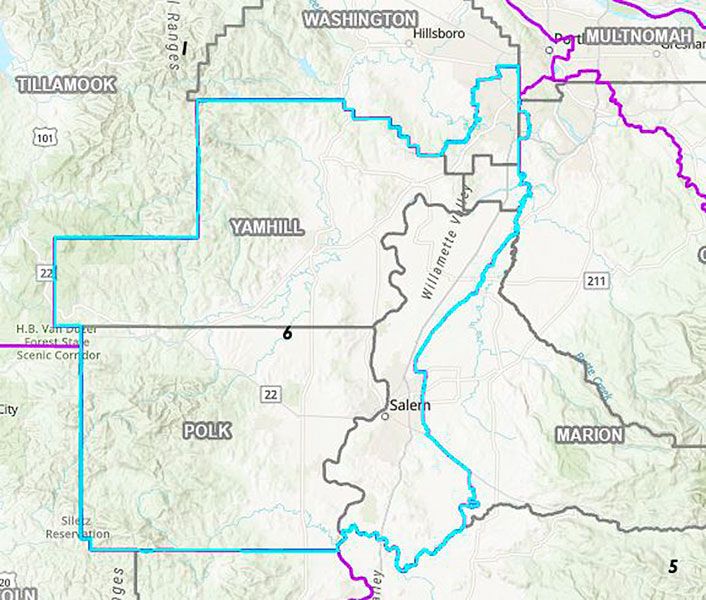

The Supreme Court’s decision means Democrats have a strong chance of maintaining their supermajority in both the House and the Senate. Princeton analysts who review redistricting data from each state predicted the new districts will result in Democrats holding 39 of 60 seats in the state House and 20 of 30 in the state Senate. They currently hold 37 in the House and 17 in the Senate, after state Sen. Betsy Johnson left the Democratic party to run for governor as an independent.

One lawsuit asked the court to throw out the Legislature’s new districts and replace them with a set drawn by a Republican political strategist to maximize competitiveness. The Princeton analysis suggests that only seven districts — four in the House and three in the Senate — provide an even shot for candidates of either party to win.

Among them is the Republican-leaning House District 12, which encompasses a vast rural area east of Eugene. The district also scooped up the Eugene voting precinct of Democratic Rep. Marty Wilde, and a second lawsuit filed by two conservative Lane County men asked the court to redraw the line separating House Districts 8 and 12 to put Wilde and his neighbors back with the rest of southeast Eugene.

Wilde, who serves in the Oregon National Guard, couldn’t comment Monday because he’s on military duty and barred from discussing politics.

A separate court challenge to the new congressional boundaries is proceeding, and a panel of five retired judges must make its decision by Wednesday.

The Supreme Court combined the two lawsuits into a single challenge and based its near-unanimous decision on legal briefs without allowing oral arguments. Chief Justice Martha Walters did not participate.

Justice Chris Garrett, who led the state’s last redistricting as a Democratic member of the state House in 2011, wrote the 26-page opinion.

“In reviewing a reapportionment plan enacted by the Legislative Assembly, this court will not substitute its own judgment about the wisdom of the plan,” Garrett wrote.

Instead, Garrett wrote, the justices could have ruled against the Legislature only if plaintiffs were able to prove that the Legislature didn’t consider redistricting criteria set out in state law or “having considered them all, made a choice or choices that no reasonable [reapportioning body] would have made.”

In addition to requiring the Legislature or secretary of state to consider factors including transportation links and existing geographic or political boundaries, state law mandates that the Legislature must hold at least 10 public hearings throughout the state before proposing new boundaries and hold at least five after proposing a new plan but before voting on it.

The Legislature, which operated committee hearings remotely through most of the year, did neither. It took no public testimony between introducing and voting on the final maps. However, the Legislature exempted itself from the existing law through a legal clause in this year’s redistricting plan.

Kevin Mannix, the former Republican state representative and president of Common Sense for Oregon who filed the broad challenge to new districts, said he was disappointed but not surprised by the court’s decision.

“Those of us in the political world recognize that this is a gerrymandered plan,” he said in a statement. “Unfortunately, that is to be expected when politicians get to draw their own district lines.”

In response to the lawsuit requesting the court shift the boundaries of two Eugene-area districts, Garrett wrote that the Legislature appeared to have followed all relevant laws, even if critics of the plan would have drawn those districts differently.

“In the end, the most that the petitioners’ arguments have demonstrated is that other possible configurations of the two districts might have been preferable to some observers,” he wrote. “But that is not the standard by which this court evaluates a challenge.”

Senate Democrats, who led redistricting efforts, applauded the court’s decision.

“I am pleased that the Oregon Supreme Court has found that the Legislature’s redistricting maps meet all legal standards,” said Sen. Kathleen Taylor, the Portland Democrat who chaired the chamber’s redistricting committee. “The Senate Redistricting Committee worked tirelessly to gather input from Oregonians across the state and use the 2020 census data to create fair districts, all under an incredibly compressed timeline. The Legislative Assembly has once again succeeded in delivering on its constitutional duty of redistricting.”

Candidates for the state House and Senate still can’t file for office until Jan. 1, though they’re free to begin campaigning and accepting donations at any time.

There’s still a chance, however slim, that the maps affirmed by the Supreme Court only last for one election. The group People Not Politicians is seeking to put an initiative on the 2022 ballot to create an independent redistricting commission. If approved by voters, the initiative would require another round of redistricting ahead of the 2024 election.

The group is now waiting for Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum to certify its ballot title, at which point it can begin collecting signatures. Roughly 150,000 Oregonians — 8% of the total votes for governor in 2018 — would need to sign petitions for the proposed constitutional amendment by July 8, 2022, to make the ballot.

Comments

Rotwang

Oregon's state animal: the blue gerrymander.