Stopping by: After a century, she’s learned to roll with it

But McMinnville’s Dee Nolf is still irked that current events disrupted her birthday plans

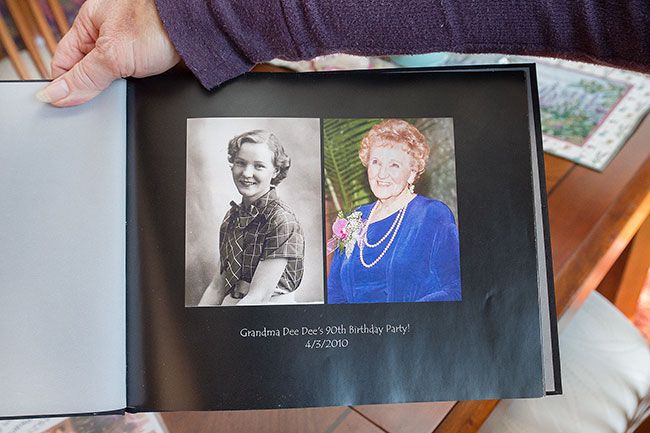

Delores “Dee” Nolf planned to travel from her home in McMinnville to Southern California this spring for a very special party, her own 100th birthday.

But boarding an airplane in the era of coronavirus wasn’t feasible, especially for someone born just after the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918. Interacting with a large group of people was out, too, even if she would like to hear friends, relatives and former neighbors sing “Happy Birthday.”

So Nolf is staying home with her daughter and son-in-law, Donna and Richard Weed. She’ll read birthday cards and blow out the candles on a small cake, maybe angel food with strawberries.

Nolf, who has witnessed good things and bad over the past century, said: “I’ve never seen anything like this.”

She shook her head about the coronavirus crisis, more irked than worried. “This is really messing up our plans.”

Nolf and her daughter usually mark the coming of spring by attending the McMinnville Wine & Food Classic. Her son, Ron, frequently comes to McMinnville for the event, as well, and sometimes cousins from Montana and Idaho.

It’s strange to see celebrations like that canceled, she said, but Nolf accepts whatever comes her way. She’s confident things will get better.

After all, she’s made it this far.

“I never dreamed I’d see 100 years, but I did,” she said.

Still, sometimes she surprised when she looks in the mirror. “Who is that old lady?” she joked, knowing most people who meet her think she’s a decade or two younger.

Nolf has lived all over the U.S. She moved to McMinnville to live with her daughter’s family about three years ago.

She started life in 1920, when America was still reeling from World War I, as well as the flu epidemic. The flu had killed her parents’ only son.

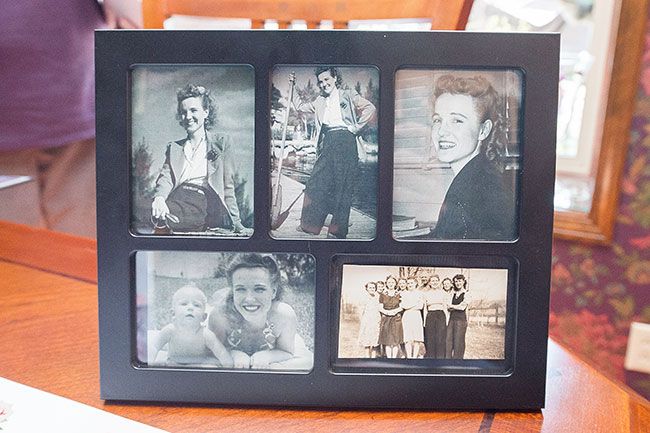

Nolf was the sixth of seven daughters in the Fraedrich family. The last girl would come along two years later.

“Then my dad went out and shot the stork,” she said, joking.

She explained, “My dad was a farmer, and farmers needed boys. We girls had to pretend we were boys and work on the farm.”

The Fraedrich girls were strong in many ways. They expressed their opinions as easily as they performed farm chores.

They were the first generation on the maternal side of their family to vote. The eldest sister cast her ballot in 1929, when she reached the voting age of 21, nine years after women won the right to vote in national elections. Nolf exercised her right to vote in 1941, the year she also turned 21.

“I’m sure after voting for the first time, Mom felt empowered,” her daughter said, “and that led to her ‘radical Republican’ stance throughout her life.”

Nolf was born April 4 — Easter Sunday, which led to her nickname “Bunny.”

“I was born in Bethlehem and lived in Nazareth,” she likes to say, enjoying how it briefly confuses people who don’t recognize the names of Pennsylvania towns.

Her parents soon left and settled on the Camas Prairie in Idaho. “I was a little sticks kid,” she said.

Between helping with the turkeys and other animals on the farm, she and her sisters made mud pies they decorated with flowers, or played in the fields and woods. They rode horses for pleasure and transportation. “We didn’t have all kinds of toys like kids today,” she said, “but we were happy.”

The family moved to Caldwell when all the girls were in school. After Nolf graduated from high school, she moved to Boise, where one of her older sisters was working as a nurse.

She attended business college, then became a legal secretary who typed and took shorthand. “I got to be pretty good,” she said.

In 1941, she and her favorite sister, Dorothy, known as “Dottie,” decided to move to a major city, choosing San Francisco because it promised excitement, she said. Another sister already lived there, as well, so they would have a place to stay.

“My boss hated to see us go to the ‘big bad city,’” she said, “but he helped us get jobs there.”

Once again, Nolf worked as a legal secretary. And she and her sisters found the city exciting. “There were a lot of guys in San Francisco” on the brink of World War II, she said. “We dated a lot.”

She married, moved to her husband’s hometown of Salt Lake City, and had a son. Coincidentally, baby Ronnie Dee was born in the same hospital as Nolf’s future son-in-law, Dick Weed.

When Nolf’s first marriage ended, her sister Vi persuaded her to join her in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Vi took care of Ronnie along with her own children, and Nolf found an office job on the military base.

Her sister was married to a soldier, and Nolf soon met one herself at a dance on the base. She and Jacob Sebastian Nolf talked, then danced under the palm trees in the moonlight.

“He was a good-looking dude and he seemed to like me very much,” she recalled. “I kind of fell in love.”

Soon, though, her soldier was transferred to California, then to Washington state. Nolf reluctantly quit her job and followed. This time, she was sure she’d found the love of her life.

“My family thought I was crazy since I had a 2-year-old,” she recalled, “but finally I loaded up my little fella and went. Jake and I celebrated Ronnie’s second birthday together.”

They married in a church in Seattle before Jacob shipped out. While he was overseas, Nolf and their son went first to her parents’ home in Idaho, then to his family’s place in Pennsylvania.

“I had to meet his parents for the first time without him,” she recalled. “They were delighted by Ronnie.”

After her husband returned from WWII service, the couple moved into their own home in Nazareth — a huge house with a basement, a gift from her in-laws. They soon had another child, daughter Donna.

Her husband, who had an electrical engineering degree from Lehigh University, built electrical refrigeration equipment. Together, they started Nolf’s Locker Plant, where they not only stored frozen food, but also did custom cutting and packaging of venison, beef and pork.

“Deer season was very busy,” she recalled.

At the time, many families relied on meat lockers. Home freezers were not yet usual.

In addition to helping with the family business, Nolf became active in her community. She volunteered at church, took part in the women’s club and helped created the Parent-Teacher Association in her children’s schools.

Nolf also joined the board that created the first public educational television station in Philadelphia. “I was invited because I’d been so involved with young people,” she said proudly.

TV was new then and, at first, not many families had televisions. The Nolfs didn’t even have a set until Donna was a teenager. But Nolf was pleased to be part of shaping the medium’s future.

She had been involved with drama productions staged by a variety of organizations over the years. She got started when a school was putting on a play and wanted to include an adult from the community.

“They picked me,” she said, recalling with amazement, “How did I even memorize all those lines?”

Nolf went on to incorporate drama in the Sunday school classes she taught for her church, the United Church of Christ. She was very active in the evangelical reform congregation for many years, and, according to her daughter, worked with “an amazing group of talented youth.”

One day, Nolf said, one of the teens brought in a record of a brand new rock musical, “Jesus Christ Superstar.”

“Very interesting,” she recalled. And when the students asked if they could perform a stage version, she said, “Let’s give it a try.”

They hadn’t seen the stage version, which had not yet reached Broadway. But they listened to the record over and over and created all the parts, said Nolf, who directed. They built sets and rehearsed with an orchestra on stage.

As the first performance approached, she recalled, “We weren’t sure about it, but we were so ready.”

Crowds flocked to the church to see the student production in April 1971. In fact, there wasn’t room in the pews for everyone, and many had to be turned away, Nolf said.

She introduced the musical first, and the audience followed along with a program that included the lyrics. The production ended with the finale from the record, which was greeted with silence — then thunderous applause.

“Then I picked up the mic and said, ‘good night, and God bless you,’” she said.

“It went over so well,” she said. “It was so beautiful.”

Nolf said she sent a letter to Tim Rice, who wrote the lyrics in partnership with Andrew Lloyd Webber, to inform them about the success of her student production. His reply told her to stop production until the show opened on Broadway.

The newspaper coverage was more pleasant. Local papers featured photos and praise for the show.

Putting on “Jesus Christ Superstar” is one of her fondest memories — “the highlight of my life,” in fact, she said. She still remembers her cast and the music, she said, breaking into a few lines from the title song, then from “I Don’t Know How to Love Him.”

After their children left home, Nolf and her husband sold their meat locker and moved to California. They’d both enjoyed living there during the war years.

They settled in Del Mar, in the San Diego area, in the 1970s. Nolf lived there for 40 years.

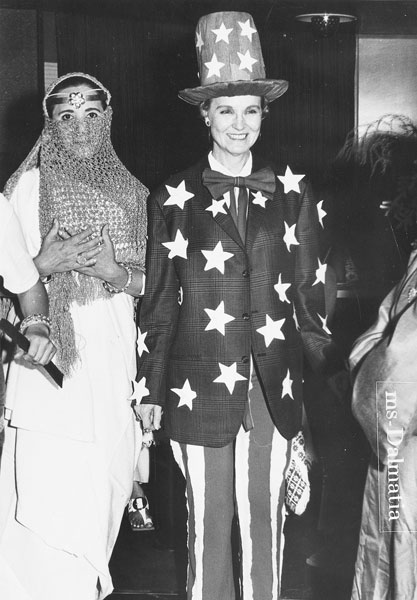

In Del Mar, Nolf said, “politics took over my life.” She was active in the local and state Republican party and Republican Women’s groups.

She even called herself “The Radical Republican” and used “DeeRedRep” for her email address.

“I was so into it,” said Nolf, whose drama skills helped her address crowds.

“We had quite a group,” she said of the local Republican Women’s chapter. “We were always involved.”

The chapter recruited young people and urged them to become politically active. It registered voters and brought speakers to address both the club and the public.

Nolf took charge of the group’s booth at the monthlong county fair, as well as serving as president multiple times.

The Del Mar group went to Sacramento, the capital, every year.

“I met Nancy Reagan, and I met Colin Powell at a rally,” Nolf recalled with pleasure.

In addition to her “Radical Republican” activities, Nolf was active in the community. She swam daily — “very good exercise,” said Nolf, who also took multiple vitamins.

She and her husband traveled a great deal.

Their daughter worked as a ticket agent for TWA, and Donna often joined her parents on excursions.

One highlight was traveling around the world on TWA’s final global flight. The family boarded a plane in Los Angeles and hopped from there to Hawaii, Guam, Hong Kong, Taipei, Bombay, Tel Aviv and New York before returning home.

Later, Donna married and settled in McMinnville. The Nolfs became frequent visitors to Oregon.

After her husband died in 2016, Nolf moved into an apartment in her daughter’s house. She joins the family for meals and activities, but lives independently.

A grandmother of three and great-grandmother of seven, she spends time emailing friends and relatives. Or she works on stories about her life and the Fraedrich family history— she has written more than 300 words.

“She’s the family tree,” her daughter said.

She also helps in the kitchen. She loves it when fresh blueberries and strawberries are in season, and freezes those, still looking to the future.

She no longer drives. She gave that up when she was 95.

All in all, Nolf said, she enjoys living here, although she dislikes rain. “I’m a Californian,” she said. “And an Idahoan, Pennsylvanian, Floridian and Washingtonian” besides now being an Oregonian.

Birthday cards can be sent to Dee Nolf at 630 N.W. Ninth St., McMinnville, OR 97128.

Starla Pointer has been writing the weekly “Stopping By” column since 1996. Contact her at 503-687-1263 or spointer@newsregister.com.

Comments