Offbeat Oregon: The summer Buster Keaton made Cottage Grove a mini-Hollywood

If a Cottage Grove logger had been bonked on the head in January 1926, and woke up six months later, he would have scarcely recognized his home town.

There was a whole new Main Street built way out east of Main Street, with businesses and boardinghouses and banks and everything. Meanwhile, back on the old Main Street, everyone in town was clustered around the Bartell Hotel, dressed in weird archaic outfits like it was Civil War times. And there were a pair of old steam logging locomotives, shined up and gleaming, parked on a siding near the two parallel railroad tracks that ran east of town.

Let’s imagine our amnesiac logger — we’ll call him Rip Van Winkle, for obvious reasons — pauses outside the hotel to watch and see what the crowd is doing. Soon the front door of the hotel opens, and out steps — hey, is that Buster Keaton? Old Stoneface himself?

It sure is. But he’s anything but stone-faced. He’s greeting people in the crowd by name, shaking the occasional hand, asking if everyone had a good breakfast.

Then someone behind him starts picking people out and sending them after Buster, who’s now striding along at about four miles an hour straight toward the locomotives.

Then the cameras come out, and crews are swarming around, and suddenly Cottage Grove no longer looks like Cottage Grove — it’s now Hollywood, baby.

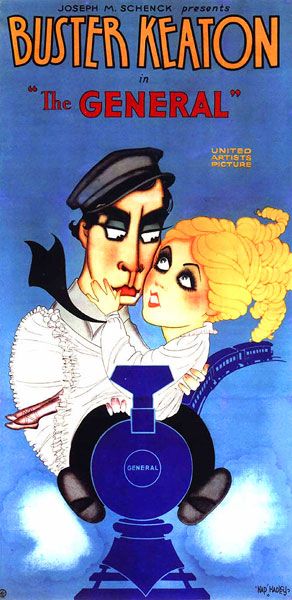

The summer of 1926 was one that would live in the memory of Cottage Grove residents for half a century afterward, and then some. The little timber town was transformed into an enormous movie set for a picture that would go down in history as the crown jewel of the silent film era: “The General”.

It started, for most residents of the town, when Buster rolled in with 18 freight cars full of props, costumes, and cameras. There were covered wagons, Concord stagecoaches, Civil War cannons, and several thousand Union and Rebel uniforms and rifles.

It had started for Buster, though, the previous winter, when he was looking for a good story to base a comedy-romance-action movie around. He’d just come off of releasing Battling Butler, which was his biggest movie success yet, so he had a tough act to follow.

That’s when he learned about the Andrews Raid, which happened in 1862 during the Civil War.

The Andrews Raid was the only locomotive chase of the Civil War, and it started as a Union incursion into the South. The raiding party snuck into Georgia in civilian clothes, commandeered a locomotive called The General near Marietta, and set out racing northward toward Nashville, which Union forces had recently taken. Their goal was to tear up the track and cut the telegraph lines so the South wouldn’t be able to use it to support its troops around Chattanooga. They didn’t get much of this kind of thing done, though, mostly because they were closely pursued by a Rebel locomotive called the Texas with a squad of Confederate soldiers on board.

The raiders made it almost to Chattanooga before running out of fuel, abandoning The General, and scattering. Only eight of their number made it back to friendly lines, two of them by floating down the Chattahoochee River all the way to the Gulf of Mexico; 14 were caught, of which eight were executed as spies and six held as prisoners of war.

Buster loved trains, and he immediately saw the appeal of a madcap train chase. So he reached out to the folks in Georgia about doing a movie on location. Best of all, both locomotives — The General and the Texas — were preserved in local museums.

The folks in Georgia were initially open to Buster’s plan to make a movie about the chase, especially since he was switching it up to make the hero a Southerner instead of a Yankee. But, that all changed when they learned it was going to be a comedy. The prickly Southerners were not yet OK with making jokes about their sacred Lost Cause — remember, this was just 60 years after the war ended, so it was still in living memory.

So Buster had to look elsewhere for two Civil War-era steam engines to do his chase with, and a place with scenery that would look more or less like northern Georgia.

He soon found what he was looking for in Cottage Grove, where logging operations were still using wood-burning steam “lokies” to haul sticks out of the woods. Some of them were old enough to be Civil War-era machines, or at least they could be with a few easy modifications.

Buster also found the entire town of Cottage Grove was over-the-moon enthusiastic about the movie, in stark contrast with the fussy Foghorn Leghorn types who’d shut him down in Georgia.

Clearly, to borrow from another great movie, it was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

The shooting was classic Buster Keaton. Buster was a bit of a madman on the set, planning and executing stunts that could easily have killed him. There were literally dozens of accidents and serious injuries on the set, including some tough bumps and bruises for Buster himself. But it was all in a day’s work for “Old Stoneface.”

Much of the filming was a bit repetitious, because there was only half a mile of the Oregon, Pacific and Eastern line with parallel tracks. For the chase scenes, sometimes involving all three locomotives (including the one that was pulling the flatcar that the cameras were mounted to), the rolling stock had to build to speed and get all their action in during the 90 seconds or so that it took to cover a scant half mile at 20 per.

Then the trains would be move back to the starting point, the cameras repositioned so the ridges and scenery behind would look different, and they’d do it again. Over and over. For days on end. If you’ve seen the movie, you’ll remember it’s mostly chase scenes — and all of them are made of 60-second takes stitched artfully together, made on the same half-mile of track.

There were also some epic battle scenes. For the occasion, Buster Keaton was made a captain in the Oregon National Guard, and a big cohort of Guardsmen volunteered to fill the roles of soldiers. They ran down a hill in Union blue, shouting and shooting and with cannons blasting merrily away; then they hurried off, changed their uniforms, and ran down the opposite hill in Rebel gray, again shouting and shooting and with cannons blasting. One can’t help thinking these guys were having the time of their lives.

Having lots of manpower on the scene got pretty important later in the summer, by the way. Wood-burning locomotives are really good at lighting off forest fires, and on days when the temperatures climbed into the 100s, the crews found themselves spending almost as much time dousing wildfires as they did shooting footage.

One big one almost got away from them, which would have been very bad news for Cottage Grove; but luckily, the National Guard volunteers were on the scene that day for a big battle scene. Dressed some in Union and others in Rebel uniforms, they charged into battle side by side against their common enemy. Buster joined them, in his underwear, beating at the flames with his trousers.

Eventually the valley got too smoky to shoot in, and the cast and crew had to retreat back to 90210 and wait the fire season out, shooting what they could on studio lots while they were there before returning to finish up in September after the smoke had cleared.

And then there was the climactic scene, which is the main thing people talk about in South Lane County when this movie comes up. It was literally a train wreck, although metaphorically it was anything but.

Buster wanted the climax of the movie to involve a locomotive falling through a burning bridge into a river. With this in mind, although he borrowed the two main lokies from local logging shows, the third he purchased outright. He had plans for that third locomotive that probably would not be approved of by its owner unless that owner was him.

Buster found a suitable bit of scenery — a spot in the Row River (pronounced to rhyme with “cow”; it’s a reference to fistfights, not skiffs) 15 miles east of town, near the hamlet of Culp Creek. At this spot the river ran through a ravine that looked, on film, bigger than it was. He had his crew literally build a short length of railroad track leading up to a 215-foot trestle bridge across it at that spot — which his crew also built from scratch. The bridge was surprisingly sturdy looking considering it was designed to fail; but, of course, it had to fail at just the right moment. To make sure it did, they fixed dynamite charges to it in a couple key spots.

The big day was scheduled for July 23, and the Cottage Grove City Council declared a holiday so that everyone could come watch. Row River Road and Brice Creek Road were lined with some 600 automobiles, and two special excursion trains brought more. It was the event of the season.

Rumor has it Buster was planning to ride the locomotive down into the river, but his wife nixed the plan. It’s probably not true, but it would have been perfectly in character for Buster! Instead, he had a paper-mache dummy made and dressed in an engineer’s uniform, and tied it into place.

Buster carefully set up six different cameras. He did several trial runs just to make sure everything was jake — a derailment at speed just short of the bridge on his hastily-built track would be disastrous. Luckily, everything was holding up great.

Then it was show time!

A crew member climbed aboard the Texas, adjusted the paper-mache “engineer,” and opened up the throttle. Then he hopped down and watched it chuffing away, building speed, heading for the bridge.

Smoke was billowing from the fires the crew had built on the bridge by this time; in the movie, Buster lights it on fire to delay the pursuing Union soldiers in their locomotive, but the Union officer orders it to hurry on: “The bridge is not burned enough to stop you,” he says (in a title card; remember, this is a silent film), “and my men will ford the river.”

The shot — well, you know how well it went; by now surely you’ve seen it. You can see the puffs of smoke from the dynamite, but only if you know what you’re looking for. The engine crashes down, the fire quenching in the river (which had been dammed up to make it look more fearsome; the upper Row is more or less a large creek, especially in mid-summer).

By the way, the wrecked locomotive and tender were left in the riverbed until the outbreak of the Second World War, at which point they were salvaged for scrap metal to be turned into Sherman tanks and such. It’s now gone, but Lloyd Williams of the Cottage Grove Historical Society told reporter Meghan Kalkstein in 2007 that bits of track and steel can still be seen in the river when the water level is low.

After the train-wreck scene, and for the next couple days, battle scenes were filmed by the ruined bridge. The dammed-up river turned out to be deeper than expected, and a few actors nearly drowned in it.

At the end of the summer, the town held a farewell picnic in the park for the film cast and crew. Everyone had a swell time, even those who had been injured in falls and explosions and such on the set.

The movie had its Oregon premier in Portland on New Year’s Eve, and it came to Cottage Grove a month later. The locals, of course, loved it; the rest of the world, not so much. Buster Keaton is a moviemaking legend for a reason, and he had noticed the public taste trending away from slapstick and toward more dramatic comedic fare.

What he had not noticed was that when the public went to a Buster Keaton film, they were not expecting dramatic fare; they were expecting slapstick, of which he was probably history’s best practitioner. So when audiences left the theater after watching “The General,” it was as if they’d gone to a Three Stooges show and found Curly, Larry, and Moe unironically performing “Hamlet.” Their disappointment blinded them to the sheer excellence of the film, and reviews were middling or bad, and sales were underwhelming.

Actually, sales were worse than underwhelming. The film cost $750,000 or so to make ($13 million in modern currency) including $42,000 for the train-wreck scene alone. Of course, that’s a tiny fraction of what it costs to make a box-office bomb today. For example, “John Carter,” Disney’s legendary 2012 box-office disaster that also starred a Confederate military man, cost $264 million to shoot.

But the industry was very different in the silent era, and the budget for “The General,” skimpy as it seems to modern eyes, was orders of magnitude bigger than the average silent-era feature film’s budget.

And like “John Carter,” sales came nowhere close to covering its costs. Records are incomplete, but the general consensus is that box office receipts came in just south of $500,000, so the film grossed a loss of 34%, plus marketing expenses and such. It pretty much ended Buster Keaton’s career as an independent filmmaker, although of course he continued to be a sought-after actor.

(“John Carter,” by the way, did lots worse. It lost roughly 100 percent of its budget and is usually number one on Internet lists with titles like “biggest box-office bombs of all time.” Which is ironic because, like “The General,” it’s a really good movie.)

But a few years after “The General” was released, the movie industry had changed enough for critics and viewers to realize it was actually brilliant. Orson Welles said it was “the greatest comedy ever made, the greatest Civil War film ever made, and perhaps the greatest film ever made.” Twenty or 30 years later, cinema buffs were still raving about it.

And its star has risen steadily since; film writer Tim Dirks introduces it as “an imaginative masterpiece of dead-pan ‘Stone-Face’ Buster Keaton comedy, generally regarded as one of the greatest of all silent comedies (and Keaton’s own favorite) — and undoubtedly the best train film ever made.” It’s ranked in 18th place on the American Film Institute’s list of the 100 greatest American films of all time. (Me and the other eight or nine die-hard “John Carter” fans can only dream of such a turnaround; but hey, anything can happen, right?)

Buster himself never lost faith. “I was more proud of that picture than any picture I ever made,” he said in a 1963 interview.

And, despite stiff competition from other movies made in the town over the years — including “Stand By Me” and “Animal House” — so is Cottage Grove.

(Sources: “The General (film),” an article by Jim Scheppke published Aug. 22, 2022, on The Oregon Encyclopedia; “Buster Keaton’s Last Stand,” an article by Julian Smith published Aug. 5, 2020, in Alta Journal; “Remains of the General,” a TV package reported by Meghan Kalkstein and aired on KVAL-TV on May 23, 2007.)

Finn J.D. John’s most recent book, “Bad Ideas and Horrible People of Old Oregon,” was published by Ouragan House early this year. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.

Comments