Offbeat Oregon: Why legendary lawman Virgil Earp is buried in a S.W. Portland cemetery

[Note: This article is a rewritten and re-researched version of an article published Sept. 27, 2010.]

Portland’s River View Cemetery is the state’s oldest nonprofit cemetery, founded in 1882 by three of Portland’s most prominent citizens: Henry Corbett, Henry Failing, and William S. Ladd.

All three of them are buried there — Ladd’s grave in particular was the target of a bizarre raid by a gang of grave robbers 15 years later, but that’s a story for another time.

In addition to the three of them, dozens of other Portland notables have their final resting place in this lovely pastoral necropolis. Walking through the park-like grounds reading headstones is almost like scanning the table of contents on a thick book of Oregon history: Sylvester Pennoyer, the nutty governor who gave Oregon two Thanksgivings; Henry Pittock, the Oregonian publisher who once commissioned a burglary to swing a Mayoral election; Capt. John Couch, the skipper who proclaimed Portland as the best spot for a deep water harbor; legendary editor, author, and suffragist Abigail Scott Duniway; John M. “John H. Mitchell” Hipple, the fugitive deadbeat dad who became the first U.S. Senator to serve under an alias adopted to hide from law enforcement; Gen. Charles Martin, ex-Oregon governor and chief actor in what was arguably the most shameful official act in the history of the United States Army; Frances Fuller Victor, the “Mother of Oregon History”; Lola Greene Baldwin, first woman hired as a paid police officer west of the Rockies; and Simon Benson, best known for the “Benson Bubbler” drinking fountains.

These are just a handful of the dozens, perhaps hundreds, of famous Oregon names you’ll find on a stroll through the grounds.

But the most visited grave at River View isn’t one of them. It’s not even the grave of an Oregonian.

The name carved into the stone is Virgil W. Earp.

Yes — that Virgil Earp. City marshal of Tombstone, Ariz., and lead participant in the notorious gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

The full inscription on the headstone reads:

In Loving Memory of My Husband

VIRGIL W. EARP

July 18, 1843–Oct. 18, 1905

God Will Take Care of Me.

Co. C. 83d. Ill.

So, how on Earth did Virgil Earp end up buried in Portland, a city he’d been in (so far as we know) only once in his life?

Well, as you can imagine, thereby hangs a tale. But to fully appreciate it, we have to dig a little bit into Virgil’s life story.

Virgil Walter Earp was born in 1843 in Kentucky, so he was originally a Southerner; but by the time he was 16 years old the family was living in Pella, Iowa, and he had fallen for a local 17-year-old Dutch girl named Magdalena “Ellen” Rysdam.

Virgil proposed, and Ellen said yes. But Ellen’s parents were furious when they learned what the kids had in mind. They wanted her to marry a respectable Dutch man, not some transplanted Johnny Reb riff-raff brat who, as Tricia Yearwood phrased it in her 1991 song about a similar situation, wasn’t worth a lick.

Virgil’s folks weren’t sympathetic either; they thought (not unreasonably, you have to admit) that he was too young to be getting married.

So the two star-crossed lovers eloped and got secretly married, in fine Romeo and Juliet style. Their two families, united by opposition to their union, got together and tried to have the marriage annulled, and maybe they succeeded, legally in any case; but the young folks had not waited for an official decision on that before consummating the marriage, and soon there was a baby on the way.

Then the Civil War happened, and Virgil was off to the trenches to fight for the Union Army. The baby, Nellie Jane Earp, was born about six months after he left. That was in mid-1861.

Two years after that, word reached Magdalena that Virgil had been killed in battle. Ellen, considering herself widowed, remarried the following year to a nice, parentally-approved Dutch man named John Van Rossum. Then, a few months after that, the Van Rossums moved to Walla Walla.

And the following year, when Virgil mustered out of the Army and came home to Iowa, he found no trace of his wife and daughter. Her parents, of course, were not going to help him find them, and neither were his; but he did learn that she had remarried. Knowing that he could now bring only trouble to the woman he still loved, he swallowed hard and moved on.

For the next dozen years, Virgil moved around the West, working as a cop, driving stagecoaches, grading railroad beds, and joining forces with his more famous younger brother, Wyatt, in various business ventures.

He married two more times: once in 1870 to a woman named Rosella Dragoo, and once (sort of) in 1874 to Alvira “Allie” Sullivan, a waitress he met on the job at a hotel in Council Bluffs, Iowa, when he was driving a stagecoach there. The records are silent on what happened to Rosella, whether it was death or divorce that parted them; but Allie would be his companion for the rest of his life, although they would never officially marry.

Virgil and Allie first arrived in Prescott, Ariz., in 1877. They’d been heading for California in a family wagon train led by Virgil’s father, Nicholas; but Virgil, Allie, and brother Newton liked Prescott and decided to stay while the rest of the family continued onward.

In Prescott, Virgil helped a posse catch a pair of wanted murderers, participating in the final gunfight when the two criminals went out in a blaze of glory. This seems to have given him a taste for frontier police work, because after that he sought almost exclusively law enforcement jobs. He got hired as constable in Prescott, and worked closely with the U.S. marshal for the area.

When, in 1879, Virgil and several of his brothers (including Wyatt and Morgan) headed for the silver-mining boomtown of Tombstone to set up a saloon and gambling parlor there, Virgil was commissioned as deputy U.S. marshal for the town.

In 1881, Tombstone police chief Ben Sippy skipped town, leaving $3,000 in unpaid bills and debts; and Virgil was appointed to replace him.

Almost immediately Virgil had his authority tested when a fire broke out and took about 60 buildings down to the ground. Before the property owners could respond, squatters flocked in and started staking claims on parts of the ruins, pitching tents and moving into them as if they were mining claims. Virgil deputized two dozen hard-eyed local men and coordinated a sweep, clearing the squatters off the land so its rightful owners could start rebuilding. No one was shot, or even injured, in the operation. It was a pretty good start.

But worse trouble was on its way. Like Matt Dillon on “Gunsmoke,” Virgil kept his town in good order and firmly enforced the laws there; but the town was in the middle of Cochise County, a wild and outlaw-infested patch of rural Arizona that was led by a crooked sheriff who was a close associate of a notorious local gang of stock rustlers and outlaws who called themselves the Cochise County Cowboys.

The Cowboys soon figured out that life would be lots easier for them if Virgil, the only straight law-enforcement officer in the county, were out of the way. So they started coming into town to try and make some trouble that might end with Virgil leaving, dead or alive.

Trouble they wanted, and trouble they got. On Oct. 26, 1881, Cowboy honchos Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury strutted into town with Colts on their hips, in violation of the town ordinance (which required all guns be checked in at a saloon or hotel immediately upon entry into city limits). Virgil deputized his brothers Wyatt and Morgan along with Wyatt’s buddy John “Doc” Holliday, and confronted Clanton and McLaury along with two other Cowboys in a vacant lot behind the O.K. Corral.

“Boys, throw up your hands. I want your guns,” Virgil told them.

Famously, they threw up their hands with iron in their fists, spitting lead at the lawmen, who were ready for them. In the ensuing firefight, three of the Cowboys were killed, the fourth ran for his life, and Virgil and Morgan both took serious but not life-threatening bullet hits.

The Cowboy who ran from the fight pressed murder charges against the Earps and Holliday, but the charges were dismissed in court. So two months later, other members of the Cowboy gang tried to take vengeance. They hid out in an empty building and ambushed Virgil with shotguns as he walked out of his hotel, nearly killing him and leaving him with a permanently crippled left arm. Three months after that, someone shot Morgan through a pool-hall window, killing him.

Wyatt and Doc Holliday sent Morgan’s body back west to the home of Nicholas, the Earp family patriarch, in Colton, Calif. Virgil followed the next day. Two of the Cowboys tried to ambush Virgil at the railroad station, but Wyatt, whose blood was now very much up, chased them down, caught one of them, and pumped him full of lead. This was the first killing on Wyatt’s famous “vendetta ride,” in which he and Holliday and some other associates chased down and killed a number of the suspected assassins. That’s a whole ‘nother story, and a fascinating one, but since it has nothing to do with Oregon history, I’ll leave it to other writers to recount, and get back to Virgil.

Virgil settled down in Colton with Allie and tried to put down roots. He worked security for Wells Fargo & Co. — using a top-break revolver that he could reload one-handed — and opened a detective agency. Later he served as town constable, and became famous for his even temper and his ability to de-escalate potentially deadly situations. His favorite less-than-lethal law enforcement technique, when force had to be used, was “buffaloing” — that is, pistol-whipping — unruly suspects.

After the “vendetta ride,” Wyatt joined Virgil, and the two of them started following mining strikes around California and Nevada, opening saloons and gambling houses, promoting boxing matches, and engaging in similar “sin industry” entrepreneurship. They went back to Prescott in the mid-1890s to work a silver mine, and Virgil was nearly killed in a mineshaft cave-in; the injuries he suffered would eventually team up with a bad case of pneumonia to kill him.

But before they did, the shock of his life — and quite possibly the luckiest break he ever caught — came his way in the mail, with the name “Mrs. Levi Law” written above the return address.

Mrs. Levi Law, it turned out, was none other than Nellie Jane Earp — the baby girl who had been born to Virgil’s first wife, Ellen, while he was away fighting the Civil War. She had grown up in Portland, reading all about the exploits of her famous long-lost father in newspapers, and had finally gathered up the courage to reach out.

The following year, encouraged by Allie, Virgil journeyed to Portland to reconnect with his family.

He had an extremely pleasant visit with his former childhood bride, got to know his lost daughter, and met several darling grandchildren.

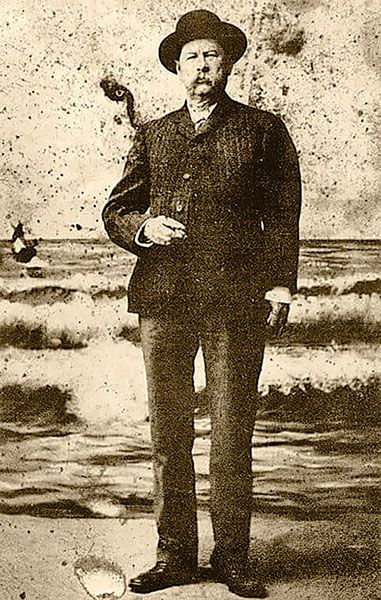

He made an especially big impression on his grandson, George Law, who legendary pop historian Ralph Friedman actually tracked down and interviewed in 1976 when he was 90 years old. “A powerful big man,” Law told Friedman. “He wasn’t fat; he was broad-shouldered. His (left) arm hung like a rag.”

Virgil was still fairly young in 1899 — still in his 50s. But he was worn out. He had lived a hard life; but as a law officer he had taken on those risks with the goal of creating the kind of country that his little family could thrive and be safe in. What he found in Portland had to have melted his crusty-old-gunfighter heart. He and Allie had never had children, whether by choice or by chance. Maybe he felt bad about that. But now it was as if a whole family had just materialized out of the clear blue sky to take him in, just as his clockwork was starting to wind down.

All too soon, the visit was over, and Virgil headed back east to the latest mining-country boomtown that he and Wyatt were working: Goldfield, Nevada. (This was just a year or two before legendary Portland shanghaier and all-around high-society bad guy Larry Sullivan came to Goldfield, by the way; the two likely never met.)

When, in 1905, the old law dog finally succumbed to a stubborn case of pneumonia, grown-up Baby Nellie asked Allie if she could lay her almost-lost father to rest close by the family he always deserved but never knew he had. Allie, who seems to have been an absolute saint, readily agreed. So Virgil’s grandson-in-law, Alex Bertrand, promptly journeyed to Nevada and brought the body back to Portland, where he was laid to rest in River View Cemetery, in the family plot, close by the cold clay that once was the cream of old Oregon’s frontier elite.

And that is why you will find Virgil Earp buried in the Bertrand family plot at River View Cemetery, in a city he’d never lived in and only visited once. But the Oregon roots of his daughter and grandchildren were strong and deep. And the places Earp had lived hadn’t been particularly kind; he’d been shot at least three times, had been through the most unrelentingly awful war in American history and had died at a fairly young age.

After such a wild and restless life, it’s a real poetic justice that his bones are resting in a place where he’s never had to shoot at or “buffalo” anyone, close by the graves of his childhood wife and daughter, surrounded by family and friends.

So, next time you’re up in Portland with a little time to stroll through River View Cemetery, you might consider stopping by Virgil’s gravesite to whisper, “Welcome home, old man; we’re glad you made it.” You know, just in case his restless spirit is still abroad.

But I’m betting it’s not, and that it’s resting peacefully in the bosom of his once-lost family.

(Sources: Hidden History of Civil War Oregon, a book by Randol Fletcher published in 2011 by The History Press; Tracking Down Oregon, a book by Ralph Friedman published in 1990 by Caxton Press; “Virgil Earp: In a Brother’s Shadow,” an article by Lee A. Silva published in the March 2018 issue of Wild West magazine; “Virgil Earp,” an article by Kathy Alexander published November 2022 on the Legends of America Website; “The True Hero Named Earp is a Permanent Portland Resident,” an article by Bill Gallagher published Oct. 2, 2019, in Southwest Connection)

Finn J.D. John’s most recent book, “Bad Ideas and Horrible People of Old Oregon,” was published by Ouragan House early this year. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.

Comments