Offbeat Oregon: The McLoughlin House’s unlikely journey to local historical treasure

To the average Oregon City resident, there wasn’t much to celebrate in the vacant, dilapidated old house by the foot of Willamette Falls.

The house had, until a few years before, been known as the Phoenix Hotel, and it had been a very flagrant bordello. Conveniently located right in the heart of what was then Oregon City’s industrial core, it had been a handy place for workers in the woolen mills, paper manufacturies, sawmills, and other operations that took advantage of the plentiful water power of the falls. No doubt it did an especially brisk business every payday.

It can’t have been brisk enough, though, because in 1906 the owners offered to sell the building and land to the city of Oregon City. There was a brief flurry of interest, and mayor E.G. Caufield got very excited about it.

But when the proposal was put to a referendum, the voters quashed the deal, and the old brothel was instead sold to the Hawley Pulp and Paper Co., which wanted the land to expand some of its adjacent facilities.

When that happened, the new mayor, W.E. Carll, dropped by to talk to Mr. Hawley. He was hoping to arrange some kind of deal to save the house. Hawley was willing to help; he said he’d gladly donate the building to the city if they could move it off the property. Carll agreed to see what he could do.

Now, this may seem like an awful lot of trouble for people to be going through to save an old brothel from the wrecking ball. The thing was, though, the Phoenix Hotel had been no ordinary brothel. It had been built in 1846, before Oregon was a state or even officially an American territory, by the “Father of Oregon” himself: Dr. John McLoughlin, the head of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Northwest operations.

McLoughlin had been posted as Chief Factor for the company in Fort Vancouver in 1825, when the Oregon territory was under joint occupancy and it wasn’t clear whether it would end up being part of Canada or the U.S. Later in the 1820s, McLoughlin had staked a land claim at Willamette Falls and platted Oregon City.

As the Oregon Trail opened up, it started becoming obvious that the huge influx of American settlers was messing up the U.S.-Britain joint occupancy treaty, pushing the territory toward full U.S. control by sheer numbers. McLoughlin, of course, was on the British side of things; but when, in the mid-1840s, American emigrants started staggering into Fort Vancouver sick and exhausted and starving from the rigors of the Oregon Trail, he took them in and gave them shelter and supplies on credit. This made him increasingly unpopular with his bosses back east, who would have preferred a more hard-nosed attitude toward the emigrants.

So, to get rid of him, they “promoted” McLoughlin to another post east of the Rocky Mountains.

This was checkmate for McLoughlin. If he accepted the promotion, he’d have to abandon his land claim at Willamette Falls, which was already very valuable and only getting more so. But the only way to decline the promotion was to retire from HBC. Which, as they had expected, was the option he took. He settled down at the falls and applied for American citizenship, which he received in 1851.

But by now most of the Oregon City residents were Protestants, and McLoughlin was Catholic. This would be no big deal today, and the Hudson’s Bay Company employees were also very broad-minded about such things — half of them being French voyageurs, after all — but plenty of the American emigrants were not.

To make things worse, there had been an unfortunate incident eight years earlier when McLoughlin had publicly attacked and thrashed Fort Vancouver’s Anglican chaplain, Herbert Beaver, in the courtyard at the fort. Beaver had referred to McLoughlin’s wife, Marguerite, as “a female of notoriously loose character” and as McLoughlin’s “kept mistress” (their marriage ceremony had not been an Anglican one) in an official report, which had passed through McLoughlin’s hands on its way east. But however deserved this public drubbing may or may not have been, it didn’t do much for McLoughlin’s reputation among Protestants.

So McLoughlin, although he was the most prominent citizen of Oregon City, had plenty of enemies there, and some of them got busy challenging his land claims.

Some of those challenges were successful, but enough was left for McLoughlin to finish his life in comfort — and to build the biggest, nicest house in the state for his wife and family.

The house was a great big Colonial-style two-story residence with numerous rooms upstairs for guests. These guest rooms, of course, would be super useful decades later, when the place became the Phoenix Hotel.

John McLoughlin died in 1857. Marguerite followed three years later, and after that for a time other family members lived in the house. But by 1867 they had all died or moved out, and the house was sold, and began its transformation from White House to brothel.

By 1908, when Hawley Pulp and Paper bought the house, John McLoughlin was universally recognized in Oregon City as one of the most important figures in state history. But he was not as universally loved. Plenty of people in Oregon City wanted nothing to do with him, or with his old house.

Luckily for all of us, Eva Emery Dye was not one of them.

Eva Dye was a famous author and the main power behind the Gladstone Chautauqua. Her most successful book had been a biography of McLoughlin, and when she learned what was planned for his house, she turned her considerable organizational skills into a bid to save it.

At first things looked like they’d be smooth sailing. The state Legislature passed a bill allocating funds to preserve the house. But then Governor George Chamberlain vetoed it, putting everything back to Square One.

So the Oregon City City Council stepped up, offering to donate the building and provide a spot to which to move it, if private donors would cover the transportation and restoration costs. The spot they picked was in the city park at the top of Singer Hill.

Dye and her allies thought that sounded just fine, and promptly formed the McLoughlin Memorial Association — one of the first historic preservation organizations in state history, if not the first — to raise the necessary money.

This appears to have been the point at which Oregon City’s anti-McLoughlin forces realized it was really going to happen. It’s not entirely clear why they cared so deeply about the old house; most likely it was a coalition of residents who considered any former brothel to be irredeemably tainted with sin, along with others who hated Catholics enough to oppose memorializing McLoughlin.

Whatever their motives, they immediately mounted a fierce resistance to anything short of demolition. First they got an injunction barring the building from being moved. The Association appealed to the local court, the judge threw it out, and work went on.

While the house was being moved, the opposition apparently bided its time. It probably looked to them like the problem was going to take care of itself when the house reached the bottom of Singer Hill. Singer Hill, as you may know, is not really a hill per se, but rather a narrow roadbed cut into the side of the great rocky bluff running through the middle of downtown Oregon City, towering hundreds of feet over the river. It’s the same bluff that Oregon City’s famous municipal elevator serves, a block and a half away to the south. Looking back and forth from the tiny, narrow roadway to the great ramshackle house, most onlookers must have thought there was no way this would work.

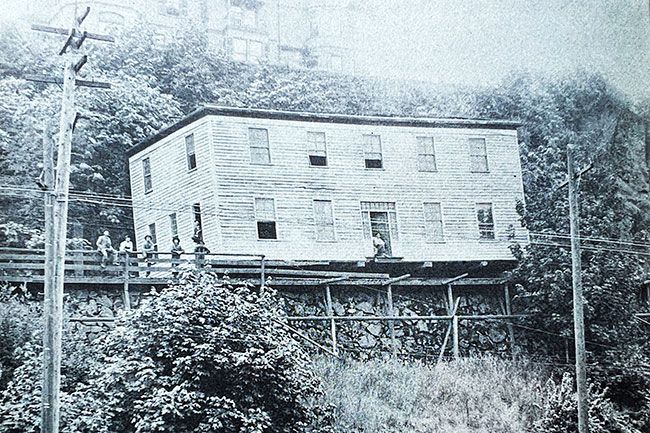

But it did. Old photographs show the process. The building was winched up the hill, inch by inch, using cables powered by a capstan wheel turned by a single horse. The house was considerably wider than the road up the hill, and at one point it was sticking so far out over the edge of the cliff that it nearly toppled off to tumble down the hill. The workers had to run down to the river for sand and gravel to dump on the floors of the inboard side of the house, to keep the center of gravity over land instead of air.

When the house was finally at the top — at a cost of $600! — another injunction was served, seeking to prevent it from being set on the foundation they’d built for it in the park. This was quickly dismissed, and the house was placed there. Then a guard had to be put on it, as anonymous arson threats came in from frustrated anti-McLoughlinites.

But eventually the drama subsided, and on Sept. 5, 1909, the house was officially dedicated in a memorial service for McLoughlin.

Today, the John McLoughlin House is something of a municipal treasure for Oregon City, and regularly attracts visitors from all over the country. If you should go and see it, which you absolutely should, take a little detour over onto Singer’s Hill afterward and try to visualize that enormous house being winched up that narrow, rock-lined roadway — by one single hard-working horse!

(Sources: “How McLoughlin House was Saved,” an article by Vara Caufield published in the September 1975 issue of Oregon Historical Quarterly; “Eva Emery Dye,” an article by Sheri Bartlett Browne published in The Oregon Encyclopedia on Dec. 20, 2021; McLoughlin Memorial Association Website at http://mcloughlinhouse.org; National Park Service)

Finn J.D. John can be reached at finn@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.

Comments