Opening our eyes to history in all shades of good and bad

Facing flawed past necessary if we are to be a nation of freedom, equality, justice

Political conservatives deplore rewritten history, which they perceive in the 1619 Project and Critical Race Theory.

However, rewriting history actually involves erasing events, achievements and people. The 1619 Project and Critical Race Theory don’t do that; rather, they seek to acknowledge and redress significant historical oversights.

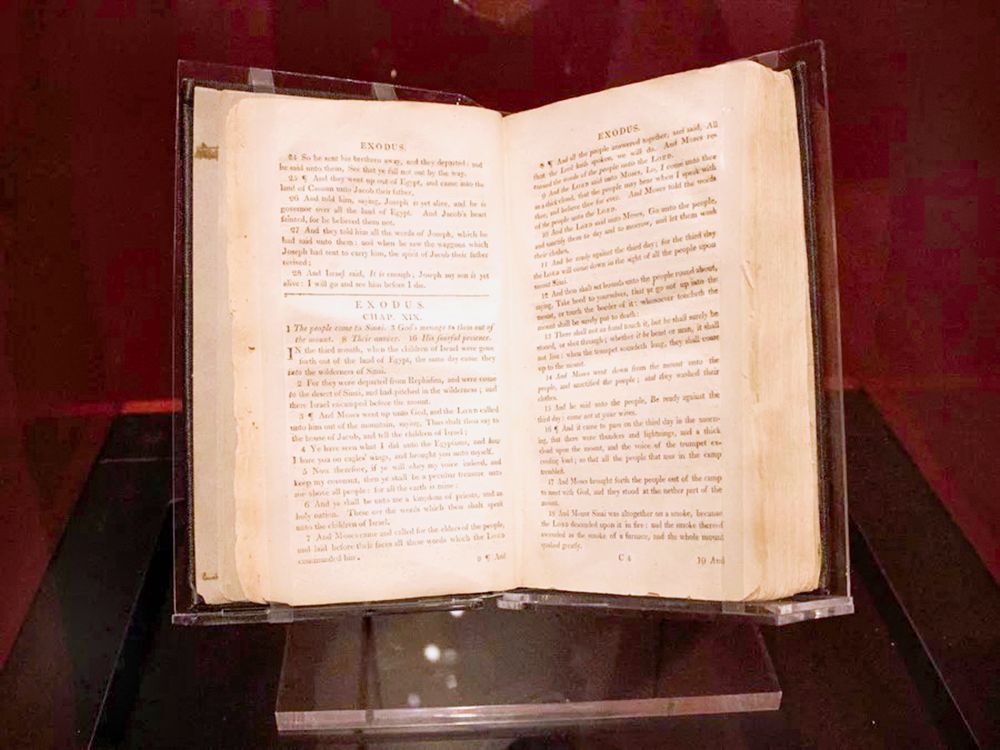

If you want rewritten history, there is no better example than “The Slave Bible,” created by the British in 1807 to convert Black slaves in the West Indies to Christianity.

This missionary project required omitting huge chunks of what Christians view as the divinely inspired Bible. The Slave Bible contained only 232 chapters of the full Bible’s 1,189 chapters.

Brevity wasn’t the objective of these edits, either.

Notably excised was much of Exodus, the epic story of Israelites, led by Moses, fleeing Egypt and slavery to go to the promised land.

It’s one of the most compelling stories ever written, describing how Yahweh freed his chosen people using plagues, guile and the parting of the Red Sea. It includes the origin of the Ten Commandments, the backstory of Passover and one of the most dramatic flights to freedom of all time.

What Exodus also did — and still does — is shine a light on people gaining freedom from a cruel oppressor. So you can understand why slave traders and plantation owners wanted to scrub this part of biblical history.

This was an omission with a motive. If truth be told, much rewritten history leaves the inconvenient parts on the cutting room floor in books about history and the law.

The story of Jesus, the very foundation of Christianity, also felt the strokes of the censor’s pen in the The Slave Bible. For example, Galatians 3:28 — “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither bond nor free, there is neither male nor female: for ye are all one in Christ Jesus” — was struck as too suggestive.

On the other hand, Ephesians 6:5 — “Servants, be obedient to them that are your masters according to the flesh, with fear and trembling, in singleness of your heart, as unto Christ” — survived censorship in The Slave Bible.

Even that involved some sleight of hand, though, as the whole point of Paul’s epistle to the Ephesians was to declare a new multi-ethnic family of God, unified in love.

Cherry-picking Bible verses, as well as history, can be problematic even for political conservatives. The grievance of conservatives reflects a lack of appreciation — or more likely a blind eye — to the difference between rewritten history and unacknowledged history.

In a recent column published in The New York Times, Rabbi Sharon Brous of Los Angeles asserts that narratives of liberation, such as the story in Exodus, are important both for the oppressed and the oppressors.

“Exodus is an archetypal redemption story, a reminder that as much as the world has changed since ancient times, oppression, degradation and exploitation remain part of the human condition,” Brous writes. “As long as there is power, there will be abuses of power.”

“But Exodus also is a reminder that any moment could be the inflection point between oppression and liberation,” she adds.

The Israelites gained their freedom from oppression.

The Pharoah could have seized the moment to liberate himself from the yoke of slave master. Instead, in anger, he chased his freedom-seeking slaves.

The story of Exodus recounts the death by drowning of his army, memorializing his missed opportunity for social and spiritual rebirth.

“America, too, needs a redemption narrative, a shared story for the America being born in our time,” Brous concludes. “Perhaps the Exodus from Egypt, once deemed so dangerous that it had to be excised from some bibles, will awaken our moral imagination as we strive to write a new story for this nation.”

She foresees a “collective liberation” in which slave and oppressor are both freed.

Those, like me, who celebrate the spirit behind the Black Lives Matter movement, 1619 Project and Critical Race Theory, believe collective liberation begins by facing our unexpurgated past.

The goal is not to stoke hatred or cast blame, but to pull back the draperies on our full history as a nation and the unfair remnants it left behind. After all, it is hard to fix what you don’t acknowledge needs fixing.

America has suffered its own plagues over freedom and liberation — the Civil War, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, lynchings, the Tulsa Race Massacre, segregation, police profiling, one-sided justice, anti-Chinese immigration laws, Japanese-American internment, separation of asylum-seeking families, antisemitism, white supremacists. None of this is a secret, but some want it treated like a secret in schools, courtrooms, workplaces and neighborhoods.

“I still believe that together we can build a redeemed society,” Brous says. “A multiracial democracy, rooted in equal justice that defends the dignity of every person and strives to embody the great, age-old vision of collective liberation.”

The implicit part of freedom is that there cannot be the oppressed and the oppressors; the humiliated and the vaunted; the broken and the blind. As the Statue of Liberty says, “Until we all are free, we are none of us free.”

The price of freedom may simply come down to brutal honesty.

We aren’t perfect. Our legacies aren’t pure. We’ve felt pain and inflicted pain.

As written in James 4:14, “Yet you do not know what your life will be like tomorrow. You are just a vapor that appears for a little while and then vanishes away.”

The oppressed and the oppressor are not so much unlike in ultimate terms. Their relative positions are temporary, mortal, reversible and revisable.

The Bible speaks in multiple places about strangers and the freedom that accrues when strangers are treated as long-lost friends. The Slave Bible may have left out this most Christian of Christ-like philosophies, but we don’t have to be so blind as to overlook it.

To realize that age-old vision that all men are created equal requires opening our eyes to our past, our entire past — not to rebuke, but to reconcile. Admitting mistakes is a sign of strength, not weakness. What we exclude from our history says more about who we are than what’s written — or rewritten.

------------------------------------------------

Guest Writer: Gary Conkling started writing stories as a child and publishing them on his own hand-cranked printing press. Little did h know digital technology would make it possible to repeat the task as an adult by publishing his own blog, Life Notes. He is a journalist by trade who has worked in the trenches of public affairs at the federal, state, regional and local levels. But he also is an observer of life occurring around him. This piece is from the blog, found at https://garyconklinglifenotes.wordpress.com.

Comments