Charles House: City, state, college helped blaze trails in electronics

At my daughter’s home last spring, a woman asked, “How do you like living in a small town?”

Puzzled, I responded, “What do you mean?”

She replied, “McMinnville only has 35,000 people.”

We had just sold our 32-horse stable in the lee of Sequoia National Park to move back to civilization. Befuddled, I answered:

“Well, we came from a town of 158 people. The next town, 19 miles up the road, had 140. And we were 23 miles from a decent grocery store. But I was in McMinnville 40 years ago, and it was smaller then — maybe 15,000 folks.”

My wife and daughter both stared at me blankly. What, they wondered? Really? Where?

My daughter, it turns out, had left for college. And my wife and I had not yet met.

I replied, “It was at a small company division of Hewlett-Packard, way out of town in a farming area. There wasn’t another building around for half a mile.”

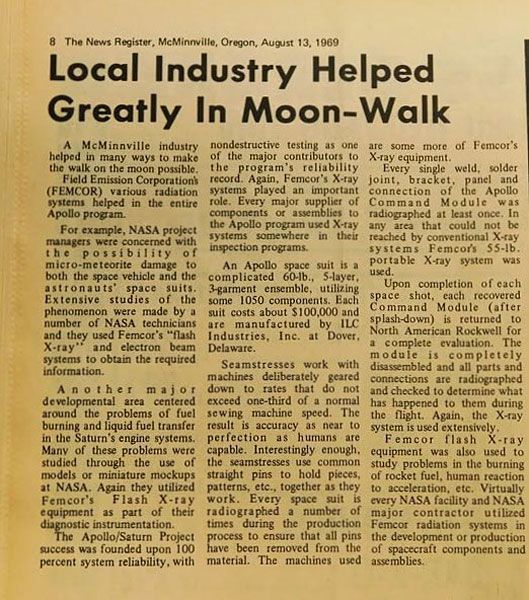

HP bought FEMCOR in 1973. A decade later, it pioneered surface-mount technology for integrated circuits, becoming the first of 91 HP divisions to master the process.

I loved the breakthrough and penned an HP article extolling the new technology. My enthusiasm waned a bit, though, when someone from the McMinnville Division, the prosaic name HP gave FEMCOR, phoned to say:

“Call off the dogs. Your article has resulted in more visits by HP people than we have employees. We can’t get anything done.”

My wife Jenny and I looked up the old FEMCOR address. As it turns out, my “way out in the country” description isn’t all that accurate anymore.

The vacant tract next door to Albertsons, now owned by Linfield University, was deeded to the school by HP. So was a large part of Linfield’s current campus, all due to the school’s FEMCOR legacy.

When HP shuttered the local division, it donated land and buildings to Linfield, more than doubling the size of the campus.

Historically, this was quite appropriate, as FEMCOR founder Walter Dyke was a long-time physics professor at Linfield. He helped establish the Linfield Research Institute in 1956, to involve both faculty and students in applied physics research, and FEMCOR emerged from that.

Back then, I had minimal appreciation for Oregon’s electronics history. But it’s substantial.

Gifford Pinchot, founder of the U.S. Forest Service, stimulated the creation of long-distance radio so forest rangers could communicate. It was explained this way by Heike Mayer in an Oregon Historical Society contribution:

“The Forest Service Radio Laboratory (FSRL) — located in Portland from 1933 until 1951 — pioneered the development and use of low-power, lightweight, shortwave wireless radio sets. This provided a way for forester rangers and firefighters to communicate in the rugged, forested terrains of the Pacific Northwest. Wireless radio was much more reliable than carrier pigeons (used during the 1919 Oregon fire season), or telephone networks requiring expensive lines.”

Meanwhile, Melville Eastham, born in Oregon City in 1885, founded General Radio in Boston in 1915, after inventing key X-ray equipment in Oregon via a precursor for FEMCOR.

GR became the giant of electronics instrumentation in the late 1920s, stimulating MIT and Stanford courses. Bill Hewlett went to MIT for graduate work, then founded Hewlett-Packard with former Stanford classmate David Packard.

HP’s first product, an audio oscillator covering both standard radio frequencies and the Forest Service’s new shortwave frequencies, was first demonstrated for the Institute of Radio Engineers at an Oregon exhibit in 1939. That led to HP’s first commercial sale.

When World War II broke out, GR teams gathered at MIT in Eastham facilities.

Walter Dyke, who later became a physics professor at Linfield, led pioneering airborne radar work at MIT. Hewlett became the Army’s liaison officer.

There, both met a young Oregonian, researcher Howard Vollum. He later partnered with Jack Murdock, a radio shop owner in Portland, whose Murdock Foundation has helped Linfield develop its facilities.

Vollum’s thesis project at Reed College was an improved GR oscilloscope. Hewlett wanted Vollum to join HP, but Packard and Vollum clashed.

Instead, Vollum launched Tektronix in Beaverton, and its scopes soon became the darling for designers of digital circuits in computers. Tek went on to became the world’s second largest electronic instrument manufacturer, behind HP.

Vollum asked Walter Dyke to join the Tektronix Board, which stimulated Dyke to found a company based on field emission research he and others were undertaking at Linfield. Ergo, FEMCOR.

Dyke remained on the Tektronix board until HP bought FEMCOR.

Linfield Professor Lyn Swanson was joined by colleagues at the Linfield Research Institute in forming a second field emissions spinoff, FEI, in 1971. This has become part of a multi-million-dollar international corporation headquartered in Hillsboro.

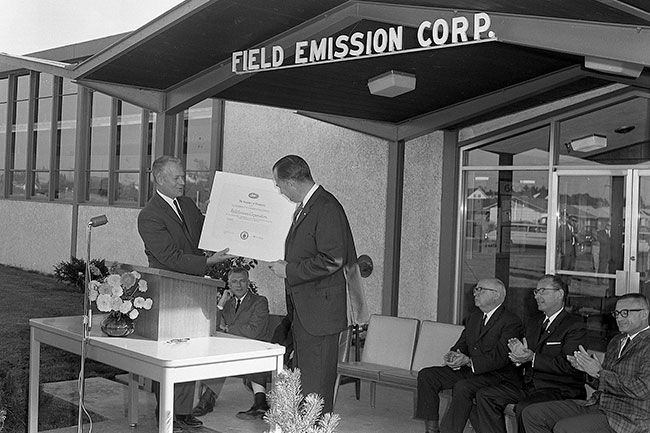

Professor Dyke, much more famous in his day than practically anyone alive today realizes, earned a presidential medal from President Truman in 1948 the prestigious David Sarnoff Award from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers In 1968.

Hewlett was a devotee of medical electronics, and he wanted to be in the X-ray equipment business. Plus, he already knew Dyke from MIT.

HP bought FEMCOR on May 16, 1973, and an article in the HP Measure glowingly described both FEMCOR and McMinnville at the time.

HP’s McMinnville Division built superb, unique products for its Medical Group. But HP began shifting out of instrumentation as its computer business burgeoned.

As Molly Walker reported in 2014, “When Hewlett-Packard closed its McMinnville-based Diagnostic Cardiology Division in 1996, about 20 engineers were asked to remain to complete a couple of projects. The crew included Neal Andrews and Steve Cooper, who ... founded the McMinnville-based Andrews-Cooper Technology, a product design firm that has come to encompass branch offices in Corvallis, Portland and Boston. Altogether, their workforce is up to 50”

And AC is still based in McMinnville.

In 1999, HP spun off its medical divisions to Agilent, which in turn sold them to Philips. Philips later sold the very high-power products line to L3 Communications, creating a division in San Leandro, California, called L-3 Applied Technologies Pulse Sciences.

It was described in a professional journal as “a leading developer of pulsed power hardware for wide ranging military and industrial applications.” The article went on to say, “Engineers and scientists at Pulse Sciences have pioneered the use of most of the high-power techniques taken for granted today: Blumlein pulse generators, Marx generators, intense bremsstrahlung and z-pinch, plasma radiation, x-ray sources, high-resolution X-radiography, low-jitter, multi-site switching systems and more.”

But in fact, the advances attributed to Pulse Sciences originated almost entirely at FEMCOR or HP McMinnville. No other company on the planet has invented tools and techniques such as these.

FEMCOR’s legacy to the world, and thus McMinnville’s, is stupendous. It should be honored much more.

Through them, luckily for me, I got to “meet” McMinnville 40 years ago!

Comments