Offbeat Oregon: Vanport residents built nearly half of US WWII aircraft carriers

During the first year of the Second World War, the conflict in the Pacific was all about aircraft carriers. With a carrier, one could take the fight to the enemy. Without one, one could only huddle on an island as a passive target, waiting for an enemy carrier’s aircraft to arrive and attack.

When the war broke out, the U.S. had seven of these precious warships, but only three were in the Pacific. They were the actual targets of the attack on Pearl Harbor — the Japanese knew if they could get them out of the way, they’d have a free hand for at least a year. It had taken more than three years to build a regular full-size aircraft carrier before the war. Mobilization would cut that timeframe to under a year, but that was still a long wait.

The Japanese almost had a free hand for that year anyway. Much of their equipment was just more advanced in 1942, especially airplanes. By the end of that year, the U.S. was down to one carrier. Both sides were hurriedly converting existing ships to bolster their fleets, but it certainly looked, from far away, as if the U.S. was not too far from ending up in that helpless position that the Japanese had hoped to put it in with the Pearl Harbor attack. Carriers were rare, complicated ships, hard and time-consuming to build. Japan had lost four of their best ones at Midway, but they still had at least six left.

And that’s about the point at which Henry Kaiser decided to go into the aircraft-carrier business.

Henry Kaiser, of course, was the man behind the Liberty Ships program. His various shipyards, including the Columbia River operations in Portland and Vancouver, were pumping out one of these slow, ugly, huge freighters at a rate of one every three days. Thousands of them. More than any submarine fleet could ever hope to sink.

In fact, they’d been so successful that Kaiser had shut down Liberty Ship production at the Vancouver yard to keep from making too many of them. It had switched over to building LSTs — “Landing Ship, Tanks” — the big cargo ships equipped with cavernous bow doors that could basically beach themselves at low tide, open their doors, and disgorge tanks, Jeeps, trucks, and just about any other kind of rolling stock, which could just drive right out onto the beach.

This was the shipyard that Kaiser wanted to use to solve the carrier problem.

The Vancouver shipyard could not build full-size fleet carriers — at least, not without considerable retooling and the loss of all the mass-production advantages that Kaiser had built his reputation on. They might be able to build an 862-foot-long, 100-airplane carrier like the U.S.S. Essex, but it would take them 10 months to do it just like it did everyone else.

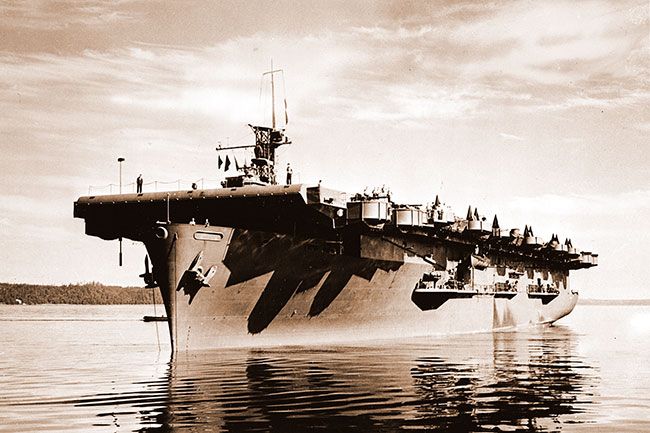

What he could do, though, was build something a little bigger than a Liberty Ship in aircraft carrier form. His Vancouver yard, he told the Navy, could belch forth fifty 512-foot-long ships, each with room for 27 airplanes, in less than two years.

The Navy authorities were not very impressed with this plan. Carriers of this size were known as “escort carriers,” and the reason for that designation was that they were mostly used to escort convoys, so that they could have some air cover against Nazi submarines in the Atlantic. They were good to have, but the Navy didn’t see them being useful for actual offensive operations and all in all would much rather have Kaiser keep pumping out LSTs.

Kaiser didn’t argue the point. He just went straight over the Navy’s head to the president of the United States — or at least to some of his close advisers.

The upshot of that was that, on Nov. 3, 1942, close to the darkest hour of the war in the Pacific, Kaiser’s employees at the Vancouver yard left their homes in Vanport on the Oregon side and reported for work on the first of these mass-produced escort carriers: the USS Alazon Bay (later renamed the Casablanca).

The Casablanca would be the first escort carrier ever built from the keel up as an escort carrier; previously, all other escort carriers had been converted from existing ships. It took a little longer to build than a Liberty Ship would have; it was bigger, more complicated, and the first of a new type. It wasn’t launched until five months later.

But it was quickly followed by the Liscome Bay, the Anzio, the Corregidor, the Mission Bay, and 45 more, in quick succession. By the time the last one had hit the Columbia River, it was only July 8, 1944. They had built 50 aircraft carriers in 16 months.

By the time the run was finished, the Navy brass had completely changed their minds about these little ships. They turned out to be incredibly useful. This makes sense, of course; by simple arithmetic, four pint-size carriers with 27 planes on each is the force-projection equivalent of a full fleet carrier.

So the Navy had gone from one full-size aircraft carrier, to the equivalent of about 15 of them, in a year and a quarter (plus the other full-size carriers that other yards were working on during that time).

Imperial Japan, on the other hand, had gone from 10 carriers at the start of the war, to five or six. Its complete output of aircraft carriers, including the ones it had on hand at the outbreak of the war, totaled just 29 ships.

As for the ships the Vanport crews were cranking out, they were literally game changers. Unescorted convoys had been easy meat for the Nazi submarines; the addition of an escort carrier with a couple dozen planes circling around dropping bombs turned them into hornets’ nests which a U-boat commander might only poke at his great peril. Submarines had to be very close to the surface to launch torpedoes — close enough to be seen and hit by one of the constantly-circling airplanes.

In combat, the escort carriers’ numbers, size, and lack of armor left their crews feeling a little ambivalent about them. They called them “Kaiser Jeeps,” which was a little confusing later on when Kaiser Motors merged with Willys-Overland in 1953 and became Kaiser Jeep Co. Their military designation was CVE, which stood for “Carrier Vessel, Escort”; the crews joked that it really stood for “Combustible, Vulnerable and Expendible.”

In the Pacific, their finest hour came in the Battle Off Samar, in October 1944, which was basically the last battle with the Imperial Japanese Navy. It was a classic hopeless “last stand” type of battle which the Americans had no business winning, but somehow did, albeit at great cost.

The setup was a Japanese gambit in which they hurled a small carrier force against the main American fleet, lost a couple big ships, and raced away. The commanding admiral fell for it and gave chase with everything he had, leaving the American troops landing on Leyte (part of the campaign to retake the Philippines) with no air cover. The main Imperial force would then show up, launch its planes, and hurl the Americans back into the sea — that was the idea.

But luckily for those American troops, three Task Units (“Taffys”), each consisting of six escort carriers and several destroyers and destroyer escorts, remained behind.

When the Japanese force — a huge armada composed of four battleships, eight cruisers, and 11 destroyers — slipped in to attack the landing troops, they ran right into one of these three Task Units — Taffy 3.

These little unarmored ships, with their handful of light 5-inch deck guns, turned back and defeated the main force of the Imperial Japanese Navy that day.

To be fair to the Japanese, the battle wasn’t as one-sided as it might have seemed. Among the three “Taffys,” the Americans had about 450 airplanes at their disposal — equal to the complement of about five full-size fleet carriers. The Japanese force had no air cover at all beyond a handful of catapult-launched seaplanes.

Nonetheless it was a spectacular success for the little Kaiser-built carriers.

After the war, Kaiser’s “Jeeps” were true surplus; there wasn’t much they could be used for. Their power plants were the main reason for this: due to wartime shortages, they had been equipped with obsolete steam engines that provided enough speed to keep up with convoys of merchant ships, but not enough to be very useful to a peacetime Navy. The surviving ships were fairly quickly mothballed and then scrapped. None of them survive today.

Which is kind of a shame, because the Vancouver-built Casablanca-class escort carriers remain to this day the most numerous carrier class of all time; no other class comes close. In fact, those 50 escort carriers represent almost half of all American aircraft carriers built during the Second World War. (Japan, by contrast, only managed to build 15 during the war.)

Not a bad showing!

(Sources: “Emergence of the Escort Carriers,” an article by Scot MacDonald published in the December 1962 issue of Naval Aviation News; The Little Giants: U.S. Escort Carriers against Japan, a book by William T. Y’blood published in 1987 by the Naval Institute Press; shipbuildinghistory.com. Summary of Battle Off Samar was sourced from Wikipedia.)

Finn J.D. John’s book, “Heroes and Rascals of Old Oregon,” was recently published by Ouragan House Publishers. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.

Comments