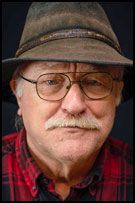

Bob Zybach: OSU has good reason to oppose Elliott Forest plan

Oregon State University and the Department of State Lands agreed in February 2019 to produce a research and management plan for the Elliott State Forest near Coos Bay by the end of that year. The plan was supposed to focus first on conservation, then on using many of the trees to store carbon from the atmosphere and sell those credits.

Nearly five years later, in November 2023, OSU President Jayathi Murthy told the department that the university would be terminating its agreements on research and management of the Elliott.

From the Elliott’s creation, selective logging there has helped pay for Oregon’s public schools. The university’s primary reason for this decision was its “significant concerns” regarding the department’s intent to move forward with a carbon sequestration scheme that would involve selling carbon credits instead of timber.

Murthy’s decision to terminate the agreement came just over a year after an August 2022 e-mail from Forestry Dean Thomas DeLuca to the department and the State Land Board.

DuLuca listed several reasons why OSU opposed the carbon-crediting scheme. He said it would pose a “serious financial risk,” increase the cost of managing the forest and make it difficult to meet the sales requirements over the long haul.

Three days before Murthy’s decision to pull out of the agreement, the Department of State Lands circulated a confidential report stating the Elliott might not qualify for the carbon market, and even if it did, the credits would likely generate less than $1 million per year. What’s more, 20% of that would go toward administering the program, it said.

Nevertheless, the department recently announced plans to continue its efforts to sell carbon credits rather than logs from the Elliott. It is slated to take a formal vote Oct. 15.

The Elliott grows about 70 million board feet of timber a year, and has a well-documented history of catastrophic wildfires, windstorms, floods and landslides.

Less than 1% of the 83,000-acre forest features old growth. More than 40,000 acres are in industrial plantations and the remainder is made up of mature trees grown in the aftermath of major wildfires in 1868 and 1879.

From 1960 until 1990, the Elliott sold 50 million board feet of timber a year, producing hundreds of millions of dollars for Oregon schools and supporting more than 400 rural taxpaying jobs. There were no wildfires during that time.

Since the Department of State Lands took over management in 2017, the forest has lost more than a million dollars a year and only funded two road maintenance jobs. The volume of unmanaged fuels is growing annually, posing an ever-increasing likelihood of catastrophic wildfire.

An example of the ephemeral nature of carbon sequestration and sale of carbon credits is shown by this summer’s Shelly Fire in Northern California, which burned more than 15,000 acres.

A report released at the fire’s height in mid-July included a map outlining 11,000 acres of burned timberland owned by Ecotrust Forest Management of Portland. That land had been used to sell carbon credits.

So, what happens next? Will money be returned to investors? Will the dead trees be salvaged or left in place to rot or burn again?

These are key questions that need to be considered and that the Department of State Lands hasn’t satisfactorily answered, according to Oregon State University.

The plan to sell carbon credits from the Elliott has already resulted in a significant amount of time and cost to Oregon taxpayers. Yet there is no indication carbon markets are stable, and even if credits from the Elliott could be sold, their value would be very low in comparison to traditional timber sales.

The Elliott was created to serve as a research forest and help fund schools through timber sales.

For two generations, it has done both. It could continue to do so, but not through sale of carbon credits.

Comments