Stopping by: Powered by insects

Its thousands upon thousands of workers don’t get rewarded with paychecks or 401K plans, though. But they do enjoy an outstanding meal plan, an all-you-can-eat buffet of fruits, vegetables and other vegetarian options.

And some of them get to start families on company time.

In return, the workers — black soldier fly larvae — consume food waste that otherwise might go to the landfill, and produce nutrient-packed fertilizer that can cause plants to thrive.

“The cycle of life. A healthy balance,” said Pat Crowley, who opened Chapul Farms Innovation and Research Center after moving to McMinnville in 2018.

He had already worked with insect-based agriculture for several years, and had appeared on the “Shark Tank” TV show with his cricket protein bars.

Based on permaculture principles, Crowley said the company is exploring “multiple benefits of incorporating insects into the modern landscape.”

Chapul — a Spanish word for grasshopper – is located just southwest of McMinnville near the South Yamhill River.

Crowley said the company is looking at building a commercial plant in the near future to allow “significantly more” production, he said.

At its current site, Chapul’s research and innovation center aims to develop the process of using insects to consume waste and generate natural fertilizer, he said. It’s also developing uses for the end products, and ways to show other farms how to do the same.

The company already has several portable modules that farmers could set up on their land, using larvae bred at the McMinnville site.

Chapul partners with Nexus PMG and the Soil Food Web on a 600-acre regenerative farm known as Tainable Labs. It also works with a variety of insect agriculture research technology and education centers around the world.

For instance, Chemeketa Community College’s wine program is studying the impact of the fertilizer on wine grapes. Oregon State University is looking at whether the insect-based fertilizer increases plants’ natural defenses against pests.

And, Crowley said, Sustainable Rituals, which sells plants and natural products in Mac Market, has been using the fertilizer. The owner was so impressed, she gave Chapul Farms the ribbons she won for her plant entries at the Yamhill County Fair.

“In the right ratio, our fertilizer is good for any plant and can be incorporated into existing soil management plans,” Crowley said, adding that trials exploring other uses are always continuing.

Fertilizer is an important product of the company’s methods, especially because of recent world events, Crowley said.

The war in Ukraine has jeopardized supplies of fertilizer around the world, and the U.S. needs to develop alternate sources rather than import much of its supply. The company received a grant from the USDA to help develop domestic, natural sources of fertilizer.

It’s not the only grant the innovative company has received. For instance, last week Chapul won a large investment grant. (Look for details about the grant and the planned expansion in an upcoming News-Register.)

Keeping food waste out of the landfill also is an important part of Chapul Farms’ mission, Crowley said.

He works with farms, restaurants, food processors and distributors to capture excess food. He also works with Linfield University, breweries and other companies to collect food waste.

He would like to collect more of the wasted food from consumers, who represent one-third of the total, as well.

So much good food goes to waste in the U.S., from vegetables that consumers think are too ugly to buy to food that’s leftover from dinner, he said.

“We waste one-third of the food produced here, 100 million tons” a year, he said.

The Oregon DEQ has developed an action plan to reduce food waste, Crowley said. The governor decreed that the state will reduce waste by 50% by 2030.

But insects eat it all, with zero waste — unlike people, they don’t care if an apple has turned brown or lettuce has become soft and slimy.

Insects also add value to the food they consume. They convert it to nutrients that are vital to the soil and the plants that grow in it, Crowley said.

“Insects are an essential part of healthy soil,” he said. “The real benefit is the microbes from the gut of the larvae. It’s a whole ecosystem that’s evolved with plants.”

Insects would eat dairy and meat products, as well, but Chapul has approval only for producing compost using vegetable matter.

The exterior of Chapul Farms’ main building looks like an old-fashioned barn. The interior also doesn’t look as high tech as the concepts with which Crowley and the other agricultural scientists are working.

The biggest room is dominated by a commercial-size grinder that chops the food into tiny pieces that become food for the larvae: barrels and boxes of overripe cantaloupe, leftover sourdough starter, vegetable trimmings from local restaurants, unused tea leaves other discarded food. Also in the fodder is scoby — yeast bacteria from kombucha, provided by a Portland producer of the fermented drink.

In another room, wingless, wormlike insects are busily consuming trays of food. A gram of the tiny fly eggs will hatch 50,000 larvae: one gram goes into each 2-by-2-foot tray of ground plant matter.

The bugs chew for a week, getting bigger and bigger, until they’ve consumed all the organic matter.

“A nature-based, green energy way to recycle,” Crowley said

Back in the main room, a large seed sorter machine separates the spent larvae from the powdery castings. Most of the insects are dried to make food for chickens, fish and other animals.

Dried larvae are available at Buchanan Cellers on the shelves next to other chicken treats.

“Chickens and fish love insects!” Crowley said. “It’s absurd that we’re feeding processed soy to animals.”

The castings and manure produced by the larvae are spread out in a greenhouse for solar drying before being bagged as fertilizer. Chapul has sold some of the fertilizer at farmers markets this year, but most goes to research; eventually, Crowley said the company will sell it wholesale.

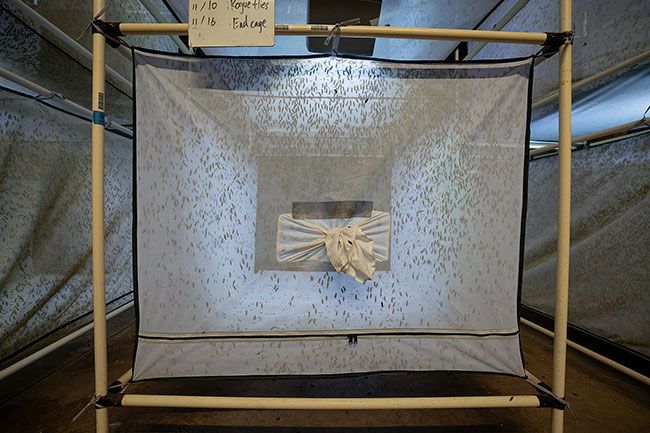

Five percent of each batch of larvae is allowed to mature into flies, Crowley said. The flies hatch in enclosed cages, laying their eggs in a special medium.

Black soldier flies don’t live long after they mature, Crowley said; just long enough to reproduce. They eat only when they are in the larvae stage; the mature flies don’t even have mouths, he said.

The flies are endemic to Oregon, he said. They are harmless, “beneficial insects” that also act as pollinators in the wild.

Adult flies are easily visible in the farms’ cages, but aren’t flying throughout the building, as a visitor may have expected.

There’s a slight smell in the larvae dining room, like a mix of rotting fruit, yeast and ammonia fumes. It’s not overwhelming.

Other than the sound of the grinder, the building is quiet. The workers apply themselves to their jobs, munching, producing fertilizer and laying eggs so the next generation can take over the important work.

Crowley likes to show off their productivity and educate the public about the benefits of reducing waste through insect-based agriculture. He has given tours to school groups and hosted young people in workforce development programs.

The company’s box truck sends a message about the farms’ efforts, as well.

Equipped with insect antennae and decorated with colorful paintings of Oregon pollinators and their habitats, the truck has been featured in the UFO Festival parade.

With a background as a watershed hydrologist, he said he is interested in longterm management of food and water security. It’s critical so the next generation can thrive — including his own children, 9, 5 and 3.

“I started Chapul before the kids were born, but now it’s more imperative,” he said.

Starla Pointer, who believes everyone has an interesting story to tell, has been writing the weekly “Stopping By” column since 1996. She’s always looking for suggestions. Contact her at 503-687-1263 or spointer@newsregister.com.

Comments

Mike

Great story