'Once you've died, you really start living'

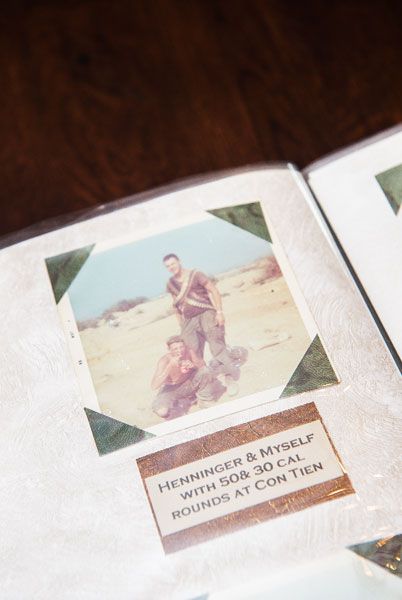

Robert “Bob” Moxley looked through his scrapbook stuffed with memorabilia of his service in the Vietnam War — local currency; propaganda fliers offering rich rewards to American G.I.s who surrender; many, many snapshots of buddies with whom he served.

He focused on one picture. “He didn’t make it,” said Moxley, whose Marines unit, the 1/9, was called “The Walking Dead” because of its extremely high casualty rate.

“He didn’t make it,” he said, pointing at another friend killed in the horrendous battles. He turned a page, noting one by one, “He was killed. He didn’t make it. He died. He was hit by a grenade.”

Moxley lost a lot of good friends in the war, “a graveyard full.” He shed tears for each one.

There are a few exceptions; men who made it home, like he did. Moxley, nicknamed “Sarge” back then, has even located a couple of friends he once mourned who, as he did, surprised everyone by surviving.

He recalled meeting a friend nicknamed “Hippie” at a reunion three years ago.

“Sarge, you died!” Hippie told him, overjoyed that it wasn’t true.

“You died, too!” Moxley cried, equally happy.

Fifty years on, thoughts of such joyous reunions make him grin like the teenager he was when he arrived in Vietnam.

Although he’s a happy man, a devout Christian with a positive outlook, the smile fades when he thinks of the war itself.

“Killing is not right. Killing is wrong,” said Moxley, a decorated combat veteran.

“It’s horrible. It’s not right,” he said. “We all felt that way.”

Still, serving in combat “made a better person of me,” he said. Because of what he experienced back then, he said, now “every day is a holiday and every meal is a banquet.”

He abides by those words, he said, observing, “Once you’ve died, you really start living.”

The Amity man doesn’t need a scrapbook to remind him of the war, his service and his friends.

He thinks of them daily.

And when a helicopter flies over, or he hears gunfire, it all comes back vividly, whether he wants it to or not. He deals with that, he said — “You just have to.”

He’s spoken to many groups and individual veterans about dealing with PTSD, he said. He’s also told his war stories many times in the last couple of decades.

That wasn’t always the case.

For years, he kept his anger and his memories bottled up, he said. He even attributed his scars to a car wreck, rather than the war.

Finally, at his brother’s urging, he started talking. “He said, ‘It’s killing you to keep quiet,’” Moxley recalled.

It has helped.

He even, finally, accepted the commendations he had long refused. His sons pinned his medals on during a ceremony in Portland in 1988.

Today, the medals march across the chest of his dress uniform. Additional awards fill a frame on his wall, displayed along with pictures of him as an 18-year-old recruit and the Viet Cong rifle that sent a bullet into his helmet two days after his 19th birthday.

On Feb. 26, 1969, the 1/9 was fighting in Operation Dewey Canyon, one of the major battles in the war. Moxley and his fellow Marines had been sent to capture a large enemy weapons cache on Hill 1044.

“Rockets, mortars and machine gun fire tore us to pieces,” he recalled.

Then a bullet smashed through his helmet, in one side and out the other, leaving a gaping hole but — he realized later — only creasing his scalp. He said he thinks the two Playboy pinups he had stuffed into the helmet for safekeeping helped cushion the blow.

At the time, though, he was bleeding profusely and expecting to die. Figuring he’d fight until he dropped, Moxley continued his attack, shooting and throwing a grenade at the enemy.

“It seemed like slow motion,” he said.

He received the Bronze Star award for his actions that day. He also brought home the rifle that had shot him, which he had captured from the enemy soldier.

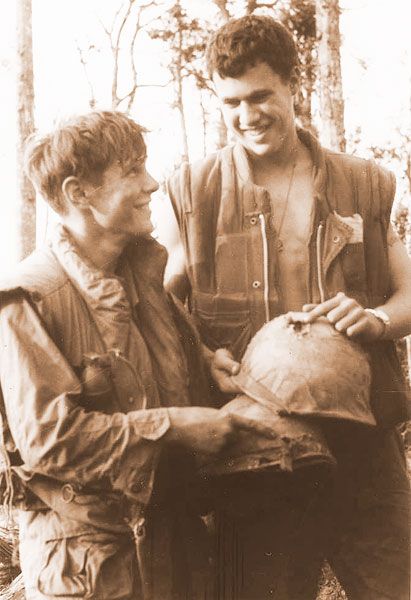

An Associated Press photographer documented the incident. His picture shows Moxley and a buddy, Ronnie Tucker, holding Moxley’s perforated helmet. The bullet that passed through it went on to hit Tucker; both men survived.

When Moxley was shot in the head, his first injury, he’d been in Vietnam for just two months.

He grew up in Eastern Oregon, then moved to Tigard with his family. After graduating from high school in 1968, he planned to enroll in Oregon State University to study forestry.

But the likelihood of being drafted led him to join the Marines, instead. He expected to be sent to the corps’ data processing school.

Instead, though, “they made me a grunt.”

Assigned to the infantry, he arrived in Vietnam on Christmas Day. He was 18 years old. “I didn’t even have to shave” that morning, he said.

When he arrived in country, he was issued two magazines of ammunition, a helmet with no liner, a canteen and boots that were too small. But the supply officer told him not to worry: He’d soon be able to pick up well-fitting boots and other supplies from casualties in the field.

He reported to his squad leader, asking him to “teach me everything you know” about fighting. He knew, he said, that he hadn’t learned enough during the eight short weeks of boot camp.

“I was already up on rifles. The outdoors have been my life,” he said. “So I adapted to jungle life pretty fast.”

He also possessed a rare skill that few soldiers had: He knew sign language as a result of growing up with deaf parents. He was able to communicate silently with another member of his unit who also could sign — very handy when an enemy is listening, he said.

Still, he was constantly aware that he could easily become one of the many who didn’t survive.

“I was scared all the time. I was terrified inside, but I couldn’t show it; I had to be strong for the rest of the guys,” he said.

The bullet that punctured his helmet marked “the start of my ordeal,” Moxley said, describing “day after day of combat” that followed.

He was peppered with shrapnel, shot in the arm, hit in the rear end. He went 10 days without food at one point, and squeezed the bark of banana trees to get water, since there was nothing else to drink.

In one battle, his unit was fighting to take a hill when enemy troops swarmed out, shooting. Moxley “hid” behind a skinny bush.

“They unloaded on me, but I didn’t get hit,” he said. “I don’t know how.”

He amended that: The bush didn’t cover him, but God did.

“What else could it have been?” said Moxley, who is deeply religious.

He carried a small Bible in the breast pocket of his flak jacket throughout the war and prayed before every patrol. He still has it; it’s worn and swollen from the damp, but readable.

He also has the ruined helmet. Weeks before it was pierced, he wrote on it: “Put trust in God,” it says on one side. “May the Lord be with you,” it says on the other. He added the initials “F.G.,” meaning “Forever God.”

“God pulled me through,” he said. “I believe God had a purpose for me.”

On June 12, 1969, a year after the infamous Tet Offensive, his unit moved into Khe Sanh. “And we just got annihilated,” he recalled. “I got my leg half blown off; I was shot in the neck; I took a load of shrapnel.”

Moxley was killed — at least, that’s what a corpsman checking on the fallen soldiers believed. He zipped Moxley’s lifeless body into a bag and marked it for removal on the “dead chopper” that transported casualties.

But in the helicopter, a gunner sat on Moxley’s body bag. “Oooff!” the supposedly dead man gasped, startling the gunner.

“We got a warm one!” the man called out as he unzipped the bag. Crying with gratitude, the gunner gripped the wounded Marine’s hand and told him to hold on.

“I watched them work on me,” Moxley recalled, although his rescuers may not have realized it.

He soon underwent the first of many surgeries. He would spend the next five years in and out of hospitals, surgical suites and rehabilitation programs. Three times, he said, doctors recommended his leg be amputated; three times, he insisted it be saved, explaining that life wouldn’t be worth living without it.

“I’m an outdoorsman; I love fishing and hunting. I had to have both legs,” he explained.

In recent years, Moxley has been reunited with the corpsman who thought he was dead and the doctor who saved his leg. The corpsman was delighted he’d been wrong. The doctor was overjoyed to meet the Marine who had been so insistent.

“He cried,” Moxley recalled. “He said he’d never heard such curse words come out of a ‘dead’ body.”

While Moxley was in surgery, his family in Oregon received a telegram informing them he’d been killed in action. They prepared themselves for his funeral.

Ten days later, they received a second message: He was hospitalized in Japan, alive but missing an arm and a leg.

As soon as he could, Moxley himself contacted relatives with even better news: Doctors had used part of an artery from his leg to save his arm, and another artery from a cadaver to save his leg.

It was 1974 before he finally was discharged from medical care. He’d learned to walk and use his right arm again. Over the years, he said, he’d also “punched two doctors and one nurse,” explaining, “you get angry in the hospital system ... you get treated like garbage.”

That’s not to say he doesn’t have great respect for medical personnel, including the field medics and corpsman who saved his life in Vietnam. “I wouldn’t be here if not for them,” he said.

By saving his life, and his limbs, he said, they “made a good life for me.”

A return to Vietnam

In 1999, Marine Robert Moxley returned to Vietnam, where he had fought three decades earlier, with three other veterans to deliver medical supplies.

For a month, they traveled north from Khe Sanh over what should have been familiar territory.

“I saw only one sign of war,” he said, describing a church with walls pockmarked from shrapnel.

He was surprised by the warm welcome he received from his Vietnamese contemporaries. “They fought against us, but now they were nice to us,” he marveled.

One former solider apologized to Moxley, asking, “Please forgive me.”

He replied, “Forgive you? We were the aggressors. Please forgive me.”

At that point in his life, Moxley had already begun telling his stories of the war. But he said “the trip back was the best thing that ever happened to me.”

After Moxley and his wife, Rita, married 16 years ago, she helped him track down fellow Marines and others with whom he’d serve or whom he’d met in the hospital. They’ve hosted several of those buddies at their home near Amity.

They moved there five years ago to be closer to their children and grandkids.

On their six acres, they keep three dogs, numerous chickens and two Jersey steers, Ronald and Donald.

“My buddies,” he called the cattle, rejects from the dairy industry that they raised from infancy.

Moxley, who studied political science at Portland State University after the war, is retired from the postal service. He started as a letter carrier, then became a supervisor in the La Grande office.

The Moxleys attend the Hopewell Community Church, where he is president of the board of trustees.

Starla Pointer has been writing the weekly “Stopping By” column since 1996. She’s always looking for suggestions. Contact her at 503-687-1263 or spointer@newsregister.com.

Comments

snobrdhideout@aol.com

Such recounting is terrifying to me even tho I was not a combat soldier , I was there, I saw the body's , had my share of the Rockets & Mortars ( too close ) Very thankful to the Marines & Army, I was Airforce In the forward Air Control working on the Spotter Cessna's They also had a tough job marking enemy positions with their Phosphorous Rockets 469 of these planes were lost between 1961-75, my job working on the planes was the Center of a Target being protected as much as possible by a circle of Army and outside the Army was another circle of Marines, They stopped two Major attacks in an attempt to overrun the Base. However they couldn't stop the Rockets & Mortars flying over their heads hitting their targets spot on coming from aprox 12 miles out.Our little spotter planes had very little chance for survival ,easy kills while spotting the Bad Guys . over all over 58,000 of soldiers did not return to their family's , most were under the age of 21.

Brad M

Great story!