Offbeat Oregon: Myrtlewood money is still legal tender in North Bend

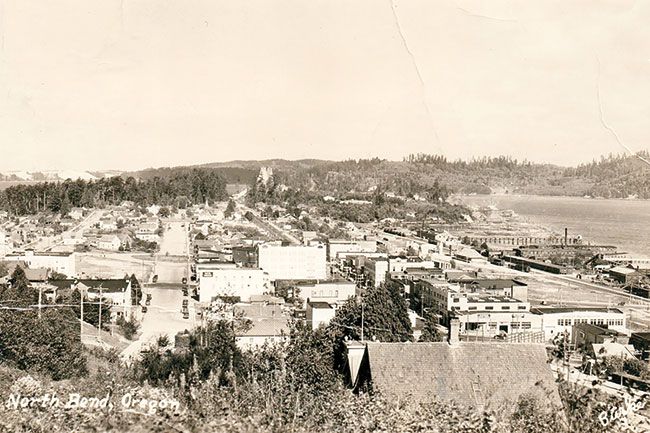

In early February of 1933, the mayor and city council of North Bend had a big problem on their hands.

It was, of course, the depths of the Great Depression — possibly the deepest of the depths. Former Oregonian President Herbert Hoover was still in office, but it was the interregnum — he’d been voted out of office three months earlier, so he was the lamest of lame ducks.

All across the country, confidence in institutions like banks was at an all-time low. Every American with money in a bank account was at least a little worried about the bank just disappearing in the night with their money. Increasingly, they were going down to the local branch like in the Bailey Brothers Building and Loan scene from “It’s a Wonderful Life,” and demanding their cash.

Nationwide, the banks just didn’t have the liquidity to come across for every nervous depositor — so they started closing and collapsing.

One of the banks that closed and almost collapsed was the only one in North Bend, the First National Bank. It wasn’t insolvent, but it soon would have been if it had kept its doors open; so its directors locked up, promising they’d reopen soon after they’d figured out how (or if) they could make everybody whole.

Initially they’d estimated it would only be for 30 days, while they negotiated a loan on their building and real estate to cover the deposits. But by the end of February, it had been 51 days, in which businesses and citizens of North Bend had been unable to access their bank accounts, and no end was in sight.

For every business or government agency in North Bend, this meant making payroll would be a tough trick.

So, early in March — about the time President Roosevelt was inaugurated and proclaimed a nationwide “bank holiday” to stem the flood — Mayor Edgar McDaniel and local businessman Irvin Ross came up with a plan:

They’d mint their own currency.

Ross’s business was Duncan’s Myrtlewood Crofters, a manufacturer of furniture and home goods made from the area’s legendary myrtlewood trees. The plan was, Duncan’s would churn out hundreds of coin-shaped disks of myrtlewood and hand them over to McDaniel, who would print on the myrtlewood using his father’s newspaper press. The wooden coins would then be sealed with shellac to protect the finish, and then they’d be ready to use to get the local economy going again.

This may have been technically illegal under the U.S. Constitution, depending on how it’s interpreted. The Constitution reserves the right to mint coinage to the federal government alone. But under the circumstances, nobody was complaining; and the city was careful to follow the spirit of the law by making no effort to create a competing currency. All the myrtlewood coins were being issued as stand-ins for real U.S. dollars, with the understanding that they would be exchanged for real U.S. dollars as soon as they became available again.

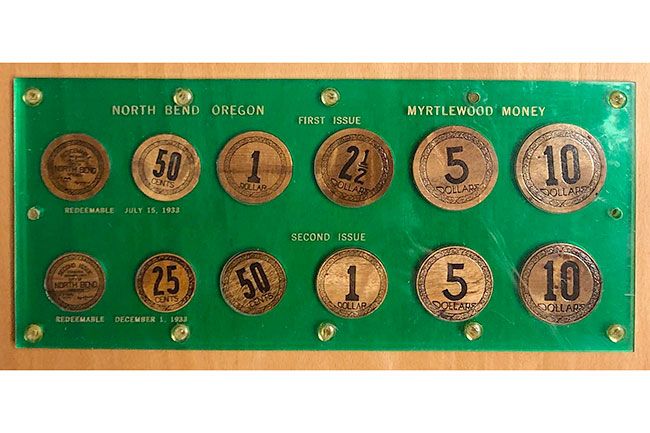

A popular joking admonition at the time was, “Don’t take any wooden nickels.” That might be why the city didn’t make any; or maybe it was just too small an amount to bother with. In any case, the smallest coin they created in that first batch was worth 50 cents; the largest was $10.

Now, $10 in 1933 was worth a pretty big wad in modern money — roughly $250 as of 2025. It’s hard to imagine someone handing over $250 worth of merchandise in exchange for a quarter-inch-thick piece of wood that the city promises to swap for cash someday — especially at a time when institutions both public and private were going bankrupt left and right.

Yet if anyone did refuse to recognize this new money, I’ve been unable to find any record of it. In fact, people seemed to love the idea.

It wasn’t an original one, or even an uncommon one. As the banking crisis deepened in the early 1930s, lots of local governments around the country had been forced to pay their employees with scrip or IOUs, and they’d been fairly creative with how they did it. The town of Heppner, in the upcountry Columbia Gorge sheep country, printed scrip on sheepskin. Pismo Beach, in California, used hand-painted clam shells.

Actually, North Bend may have gotten the original idea from the town of Tenino, in Washington. There, the local bank had collapsed a year and a half earlier, and the local Chamber of Commerce had stepped in with a plan by which account holders would assign 25 percent of their bank balance to the Chamber, receiving in exchange dollar bills made of wood, printed on postcard-sized slabs of fir with the local newspaper press.

But what made North Bend special was the material they made their money with. A persistent local story claims the myrtle tree grows only in two places on Earth — “Oregon and the Holy Land” — which is not true. Myrtlewoods do not grow in the Holy Land, or anywhere else except the West Coast; and their range here extends well into Northern California.

So it’s a special wood — usually the most expensive domestic hardwood on the shelf at your local Woodcrafter’s store — and in addition to being rare, is uniquely beautiful stuff.

The other unusual thing about North Bend’s money is the fact that it’s still legal tender in North Bend to this day (although you’d have to be a fool to use it as such — more on that in a minute).

North Bend issued two press runs of $1,000 each, the second one using a different design so that fewer coin blanks would break under the weight of the press.

Within a few months after the second run, the bank was out of difficulties and the city was once again able to get its municipal paws on its money. So they put the word out: Time to redeem your myrtlewood coins, everyone!

A few people did redeem them — especially the big-dollar coins, the $5 and $10 pieces — but by that time the coins had developed a special cachet. Many people were reluctant to give them up.

After making several appeals to coin holders to hurry up and bring them in to swap for greenbacks, the city gave up and announced that myrtlewood money would remain legal tender forever in the city of North Bend. Any time someone wanted to come cash one in, the money would be ready.

And until a few dozen years ago, this happened from time to time. But the coins have become rare enough to interest collectors, and valuable enough that only a fool would redeem one for face value.

Particularly desirable are the $10 coins, which, because they represented a large amount of money in the depths of America’s worst-ever recession, were far more likely to be redeemed for cash in the early 1930s when the city was still destroying redeemed coins.

If you happened to have one, you can still take it in to the North Bend Starbucks and use it to pay for your latte. Of course, you would never do such a thing, because any myrtlewood-money piece is worth many orders of magnitude more than face value today.

“I would say at a minimum the most common are worth from $20 to $30 on the retail market,” local historian and former coin dealer Dick Wagner told OPB reporter Bryan Vance. “And the more expensive ones get you into the hundreds, and the rarest ones — the $10s — can’t be priced because they’re so rare that they just don’t trade.”

As for complete sets of 10 (five from each press run) — fewer than 10 survive. One of them is in the collection at the Chase Manhattan Bank in New York, which acquired it as soon as the second set of coins was minted.

One set changed hands for $2,600 in an online auction early 2021; the general consensus is that this was well below what they likely would have sold for at retail.

But one thing is for sure: If you bring one of the remaining sets in to City Hall, they’ll at least give you $35.75 for it — face value!

(Sources: “The Oregon town where money grows on trees and wood is as good as cash,” an article by Bryan M. Vance published Sept. 7, 2018, at opb.org; “Tenino’s Wooden Money,” an article by Tenino City Historian Richard A. Edwards published June 2020 at cityoftenino.us; Oregon Curiosities, a book by Harriet Baskas published in 2007 by Globe Pequot; oregonencyclopedia.org; Stephen Album Rare Coins auction listings)

Finn J.D. John’s most recent book, “Bad Ideas and Horrible People of Old Oregon,” was published by Ouragan House last year. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.

Comments