Offbeat Oregon: 'Like the ocean had become vertical'

On the evening of March 23, 1964, Seaside resident Margaret Gammon hadn’t been asleep more than an hour or two when she was awakened by howling.

It was the community fire siren, blaring at full blast without stopping. She looked at the clock. It was 11:30 p.m.

“I lay in bed thinking to myself, ‘Why doesn’t that fellow at the fire station get his big thumb off the siren button so we can all go back to sleep, and let the firemen take care of the fire?’” she recalled later, in an article for Oregon Historical Quarterly. “In just a few seconds the cars started zipping up our street toward the highway like the devil himself was on their tail. I thought it must be a tremendous fire, so I figured I’d get dressed and go watch it.”

It didn’t take long for Gammon to learn that it wasn’t a fire. It was a tsunami — and it was almost upon her.

“When I got as far as the 12th Avenue bridge over the Necanicum River, the water was right under the decking, black and ominous, and covered with great chunks of white foam floating on the surface like huge ice cakes,” she wrote. “I learned later that I had crossed over the 12th Avenue bridge at the very height of the tsunami.”

It wasn’t until the next morning that Gammon learned how lucky she’d been. Her neighborhood was high enough to stay out of reach of the waves. Others were not.

“Venice Park, a residential area just north of us and right on Neawanna Creek, had been hardest hit,” she wrote. “Several houses had been wrecked completely by the more than four feet of water that swept through them. It tumbled autos like matchsticks, leaving them pinned against houses when the water receded. I noticed hundreds of tiny fish still alive and wriggling frantically in their efforts to get back into the tiny creek, now within its banks and more than 50 feet away from them. Water perhaps two feet deep had surged over Highway 101 north of Seaside at the junction of City Center route and the through route south.”

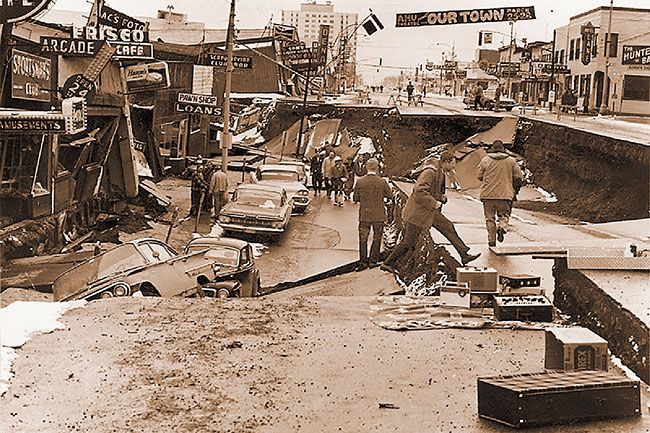

The 1964 tsunami was launched by a massive event known as the “Good Friday Earthquake” epicentered in the ocean a few dozen miles off Valdez, Alaska. Measuring 9.2 on the Richter Scale, the quake was the strongest ever recorded on U.S. soil, and the second strongest ever worldwide. It shook Southeast Alaska, including Anchorage, for nearly five minutes.

The quake itself carried a surprisingly low death count: just nine people were killed in it. But the tsunami the quake launched was another story. Nearby the epicenter, it was up to 220 feet high. It wiped out whole towns and Native villages, including Valdez — which, although not completely destroyed, was damaged badly enough that residents opted to move and rebuild the whole town farther inland on higher ground. The tsunami killed a total of 120 people in Alaska.

Down along the West Coast, wave heights were smaller, but still high enough to be deadly. Twelve people died in Crescent City, Calif. In Oregon, Monte and Rita McKenzie and their four children were camping on the beach in a driftwood shelter at Beverly Beach State Park when the tsunami hit. Struggling in the churning surf and flying driftwood, Monte and Rita McKenzie struggled to hang onto their four children, only to have all of them ripped away and carried out to sea. Louie, Bobby, Ricky, and Tammy McKenzie (ages 8, 7, 6, and 3 respectively) were drowned. Theirs were the only tsunami deaths in Oregon.

But there was plenty of property damage, all up and down the coast.

In Neskowin, Kathleen Clark got a terrifyingly complete view of the entire tsunami cycle from the front window of a vacation rental she was staying in with her brother and boyfriend.

Recounting the story to The Oregonian’s Lori Tobias, Clark said they had the window open and were enjoying the sounds of the surf when suddenly those sounds went away. The three young people looked at each other, baffled, then got up and looked out toward the sea.

The moonlight was shining on a vast expanse of wet sand. The ocean had retreated, literally beyond the reach of their sight in the moonlight.

“And then as we were watching, there was this wall of water coming at us,” Clark told Tobias. “Just a straight wall. Like the ocean had become vertical. It was a tremendous roar coming in. The water came into the little yard out front. We were just flabbergasted, just frozen in place. If the wave had been a foot higher, I bet it would have taken out the plate glass window.”

All told, the earthquake and tsunami dealt out $2.8 billion (in 2022 dollars) in damage, and killed 136 people. But scientists quickly figured out it could have been worse. A lot worse.

The majority of the tsunami deaths in 1964 were from communities near the epicenter, in Alaska. There, waves hundreds of feet high slammed into the beaches within a few minutes of the earthquake that launched them. Most Oregon beaches got a far smaller, more attenuated version of the wave, arriving hours later.

That wasn’t the case in the year 1700, though. In that year, the epicenter of the quake was right off the Oregon coast, in what we today call the Cascadia Subduction Zone. Waves hundreds of feet high came ashore within 15 minutes of the quake and washed entire villages out to sea. And scientists say similar earthquakes happen relatively regularly off the coast … on the average, every several hundred years. Scientists are currently estimating there’s a 37 percent chance one will strike sometime in the next 50 years.

With that in mind, today Oregon has two tsunami warning systems: One for faraway events that send waves around the world, and one for the bigger, deadlier local kind. But the best advice is the most intuitive: If the ground shakes, and you’re on the beach, get off it as quickly as you can and get to high ground!

(Sources: “Coast Experiences,” an article by Margaret E. Gammon published in the September 1976 issue of Oregon Historical Quarterly; “Tsunami generated by Good Friday quake devastated Oregon Coast 50 years ago,” an article by Lori Tobias published March 24, 2014, in the Portland Oregonian; U.S. Geographical Survey’s Web page on the 1964 earthquake; Portland Oregonian archives, March 28-29, 1964)

Finn J.D. John’s book, “Heroes and Rascals of Old Oregon,” was recently published by Ouragan House Publishers. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.

Comments