Offbeat Oregon: How Oregon almost became part of Canada

For most people today, the story of the original colony of Astoria is remembered — if it’s remembered at all — as a dismal failure. It was an ill-equipped party sent out by a rich guy in New York, which failed and was forced to sell out at fire-sale prices to the British.

And yeah, that’s all kind of true … but the most interesting thing about Fort Astoria is, if John Jacob Astor’s explorers had stayed home — or even left the following year — the Oregon country would probably be part of Canada today.

Going a bit farther (and being quite a bit more speculative) — if Astor had made even slightly less awful hiring decisions when he launched the project, the British would likely have ended up locked out of the entire central West Coast, from Mexico to Alaska; and it’s possible, if not likely, that it would be its own independent country, governed or ruled by Astor’s descendants.

To explain all that historical what-iffery, I need to give you a CliffsNotes version of the story of the Astoria project.

It started when John Jacob Astor, a very active German merchant who had made an enormous fortune trading beaver and other furs from the woods of the Great Lakes states, learned what the Lewis and Clark Expedition had found around the mouth of the Columbia River. Realizing that this was an enormous trading empire just sitting there up for grabs, he started making plans for the foundation of the Pacific Fur Company.

Astor’s plans were stupendous and audacious. He wanted to send an overland party following the tracks of Lewis and Clark, establishing trading posts along the way, out to what is today Astoria. At the same time, he’d be sending a sailing ship “around the horn” to establish a great “emporium” at the mouth of the Columbia, roughly where Fort Clatsop had been.

Then his trappers and traders would run up and down the Columbia and its tributaries and along the coast, trading with Indians for beaver and otter pelts and paying for them with cheap knives, glass beads, and itchy blankets. The pelts would be shipped out across the Pacific to China, where the Mandarin class prized otter pelts especially to trim their robes and paid steep prices for them. Back the ships would come, then, holds crammed with goods from China, to reap even more huge profits selling black tea, silks, china, and other exotic goods in European markets.

It would be a huge trading empire springing to life at the mouth of the Columbia River and making tremendous amounts of money.

To implement his vision, Astor hired two key leaders. For the overland party, he tapped a New Jersey businessman named Wilson Price Hunt; and for the waterborne party, a rigid, abrasive Navy officer named Jonathan Thorn.

Astor referred to Thorn as his “gunpowder man.” As captain of Thorn’s sailing ship Tonquin, he was an absolute martinet, very decisive, and a strict disciplinarian. Astor picked him because at this time the British were making a habit of stopping American merchant ships and kidnapping sailors to be pressed into military service in the Napoleonic Wars. And indeed, early in the voyage, a ship did try to stop the Tonquin, most likely for that purpose. It was Thorn’s time to shine, and so he did, manning the ship’s 10 cannons and making it very clear that the other ship would have to fight for it; it sheered away.

But the passengers and crew of the Tonquin would have probably been much better off it they HAD been drafted into the Royal Navy. The majority of them would be dead within a year because of Thorn.

Thorn was, to give the devil his due, a brave man. He was also, unfortunately, completely without impulse control when angry — and he was often angry. And he had a streak of malice that didn’t always stop short of murder.

His job was to bring a large cohort of passengers — mostly partners, whom Astor was paying for their services with a slice of the business, along with a number of French voyageurs and clerks and clerical workers — around to the new colony.

Thorn got off to a bad start right away by trying to impose an 8 p.m. curfew on the partners. Thorn, the Navy officer and ship captain, saw mutiny and insubordination in nearly everything these mountain-man fur traders did; they, in turn, considered him an employee.

Things reached a head when the ship stopped at the Falkland Islands to refill its water casks. While a big party of the partners were ashore on the treeless, foodless island, Thorn weighed anchor and tried to maroon them there, apparently figuring Astor would be well rid of such unruly dopes.

Fortunately for the marooned men, one of their friends pulled a pair of pistols and told Thorn, “Turn back, or you are a dead man this instant.” The ship got to them just in time, as the marooned men had been pulling after the ship in their rowboat; they’d just broken an oar and were well on their way to being swamped in the open sea.

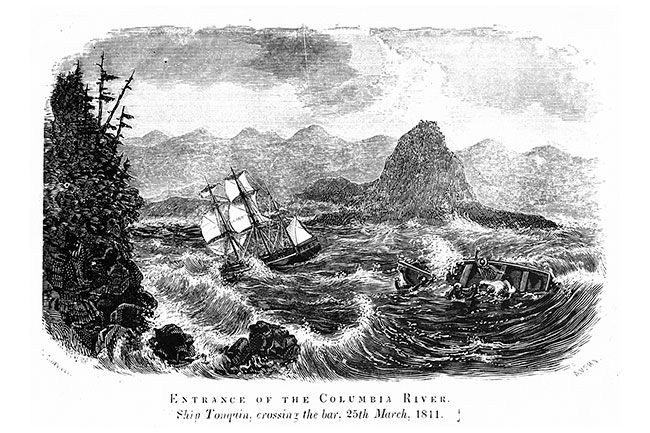

When the Tonquin arrived at the mouth of the Columbia, Thorn ordered his first mate, Mr. Fox, whom he was feuding with because Fox had befriended some of the passengers, to launch a rowboat and sound out the channel across the bar. It was tantamount to a suicide mission, as the seas were very high. Thorn staffed the boat with voyageurs, risking only Fox and one other sailor from his crew.

The boat got not far from the Tonquin when the signal flag was waved in a distress call. Thorn ignored it, and soon it disappeared, along with all its occupants. The boat was never seen again.

Another boat was launched after the seas had quieted a bit, but failed to find the channel. Then a third boat did find the channel, but Thorn, his thirst for blood apparently not yet fully slaked, sailed straight past the boat and into the bar, making no attempt to stop for or even throw a rope to his benefactors. They had to make their way ashore as best they could. Two of them, against all odds, actually survived.

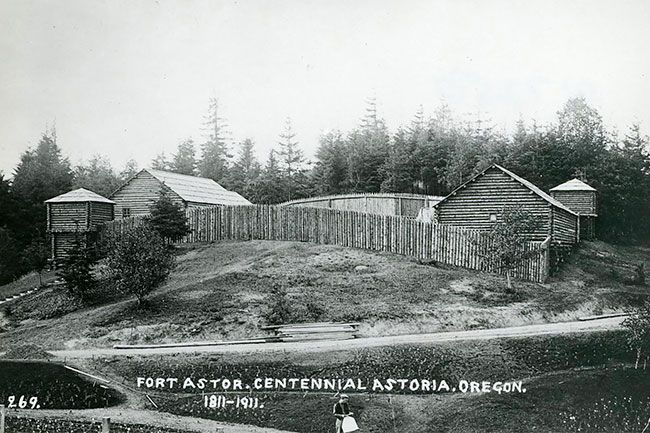

There, in Baker Bay, the company men disembarked with their trade goods and supplies to build Fort Astoria. Then Thorn sailed the Tonquin out to do some trading among the Indians.

For his first foray into trading for sea-otter pelts, Thorn put into a little cove on Vancouver Island. There, he attempted to impose his Navy discipline on a First Nations chief, barking out an unacceptably low price in blankets and knives and getting angry when it was not immediately agreed to. Finally, without having budged on his price, he seized the chief and threw him ignominiously overboard.

The next morning, the Indians returned to the Tonquin, accepted Thorn’s price, and started trading. But, just as Thorn was probably starting to think he’d cracked the code for negotiating with Indians, one of their leaders gave a signal, and they whipped out knives and war clubs to avenge the insult to their chief.

The next day, the sole survivor of the attack touched off the powder magazine, and that was the end of the Tonquin, along with a great many Natives who had climbed aboard to explore their prize.

But a good deal of damage had been done. Thorn’s bargaining style had not only cost the expedition its ship and stranded Fort Astoria in the wilderness, it had sent a really powerful message that the “Bostons” were dangerous and untrustworthy. Other American traders kept reinforcing this message — one signed the death-warrant of the Astorians’ whole upriver trading operation by having an Indian lynched for stealing a goblet even though the Indian returned the goblet when asked about it.

Stranded in Fort Astoria, one of Astor’s partners, Duncan McDougal, became convinced the Indians would soon turn on them and slaughter them. The crafty McDougal headed this off by pretending to have a “bottle of smallpox” which he would uncork if attacked. Whether this kept an Indian attack from happening or not is debatable — McDougal was himself a devious schemer, so he was always on the lookout for evidence that others were scheming against him — but it certainly didn’t make the Astorians more popular and it did little to shake the growing impression among the local tribes that the “Bostons” were just too unpredictable and dangerous to do business with.

That included selling them fish and venison. The Indians, who had flocked around the fort to trade when the Astorians first arrived, now disappeared into the woods. They seemed to be actively avoiding contact. It was going to be a hungry winter.

Meanwhile, a little northwest of Missouri, the overland party was reaping similar harvests of bad decisionmaking by American explorers. Specifically, it was something Meriwether Lewis had done several years before, on the way back with the Lewis and Clark expedition. When a couple Blackfeet lads tried to steal some of their horses, Lewis’s party stabbed one and shot the other.

For Blackfeet, stealing horses was a lark. Killing someone for stealing a horse, to them, was like hanging the kid who painted the town water tower John Deere green. Lewis made it infinitely worse by hanging a Jefferson Peace Medal around the neck of one of the corpses.

After that, Blackfeet became implacable enemies to not only American traders, but Spanish, French, and British as well. So the Astorian party had to find a way west that didn’t cut through Blackfeet country.

They actually did pretty well for about the first two-thirds of the journey, although their leader, Wilson Price Hunt, seemed not to understand the need to hurry so that winter would not catch them in the mountains.

But then one day they found themselves standing by a sweet little river flowing northwest — the direction they wanted. The river was quick, but calm. And the footsore Voyageurs, those expert paddlers, were overjoyed to see it.

The voyageurs convinced the rest of the team that they should give up their horses and take to the water. Hunt, whose response to a tough decision was usually to think about it a long time and then put it to a vote, went along with the plan, and so the party got busy hollowing out big cottonwood logs into dugout canoes before launching in the river — Henry’s Fork, which drains into the Snake.

Anyone familiar with the Snake River’s reputation for navigability can guess what happened next. They found themselves stranded, with no horses and not much food, having lost at least half the canoes to the “mad river,” in the middle of the Snake River Desert in what’s now southern Idaho.

Most of the overland crew did manage to get through to Astoria. But they only managed to beat a rival British expedition by a few months, and they utterly failed in the part of the plan that involved establishing trading posts along the route.

Then the War of 1812 broke out.

A significant number of the partners and employees of the Astorian project were British subjects. All of them now felt a little weird working for the Americans, even in a strictly commercial context. To make matters worse, Wilson Price Hunt, the guy who was supposed to be in charge, had sailed off on the Beaver, the ship Astor had sent around to replace the Tonquin, and did not return for more than a year, as the ship’s captain had opted to spend the winter in Hawaii and return to Astoria in the spring. So the British partners kind of had a free hand in his absence.

At the urging of the crafty Duncan McDougal, they used it, and sold out their operations to the North West Company. Astor was not consulted and, of course, he was livid when he learned what McDougal had done. But he could do nothing about it, and when Hunt finally came back to the fort he was supposed to be in charge of, he found a British flag flying over it.

And with that, the Columbia River was entirely in British hands.

A month after the sale, the British warship Raccoon sailed into Baker Bay and “seized” the newly purchased fort. When told that he was seizing British property, the captain retorted that his orders were to seize the fort, and he was doing so.

The fact is, the captain and his crew felt very misled. They’d been expecting several fat Yankee trading ships and a warehouse full of valuable otter pelts under a foreign flag, which would mean the sailors would all stand to gain a bit of booty as a prize of war. Finding very little of the good stuff, and what there was under a friendly flag and therefore off limits, was not a welcome sight for them, and they were not inclined to do anybody any favors.

Now comes the really interesting part. When the war ended, part of the negotiations centered around the Oregon territory, and who would get to claim it: Britain or the U.S. The final treaty stipulated that all prizes taken in the war must be returned, resetting everything to the status quo ante bellum.

Well, the status quo ante bellum involved an American flag flying over the most important spot at the mouth of the river. It wasn’t sold until after hostilities broke out.

So the Astorians briefly got the fort back — although they immediately returned it to the people they’d sold it to, as a deal was a deal.

But the most important result of this was, at the treaty table, both the U.S. and Britain had claims and credible presences in the Oregon territory.

So when their status was made official by the resulting treaty, the official status of the Oregon country changed from “up for grabs” to “joint occupancy.” That meant any Brit or any American could move to Oregon and claim land.

Imagine for just a second that Fort Astoria was sold a year earlier — just before the war broke out. In that scenario, the whole Columbia River is British. It wouldn’t even come up in the treaty, most likely. Sooner or later, negotiations would ensue about where exactly the limits of the Louisiana Purchase ended and the British Oregon country began, and the border would likely have ended up somewhere around the Continental Divide or maybe a little to the west.

Had that happened, the Oregon Trail would have been a dead letter. Nobody was going to launch a fleet of prairie schooners to homestead in Wyoming or Montana, and few American citizens were likely to want to try and travel to Oregon and arrive tired and broke and hoping for the best, if Oregon was foreign territory.

Those Oregon Trail emigrants flooding out to Oregon and setting up housekeeping were the pressure that pushed the British to relinquish their claims on the Oregon country. It was just too full of Americans for them to hang onto it with the small handful of fur traders and Hudson’s Bay Company men they had there.

Feeble and incompetent as they were, the Astorians did beat that British expedition and established an undeniable colony in Oregon. Had they not done that, Astoria would have been founded by the British North West Company, and the United States would have been very unlikely to be able to establish a presence in Oregon.

And then we’d all be speaking Canadian today, eh?

(Sources: Astoria: John Jacob Astor’s and Thomas Jefferson’s Lost Pacific Empire, a book by Peter Stark published in 2014 by Harper Collins; oregonencyclopedia.org)

Finn J.D. John’s most recent book, “Bad Ideas and Horrible People of Old Oregon,” was published by Ouragan House last year. To contact him or suggest a topic: finn@offbeatoregon.com or 541-357-2222.

Comments