Stopping By: At 100, still writing, still ‘happy as can be’

Even in hard times, newspaper columnist looks through ‘Rohse Colored Glasses’

News-Register columnist Elaine Dahl Rohse celebrated her April 12 birthday in an odd way.

Instead of floating down the Danube with her son, Mitch, daughter-in-law Louann and a boat full of new friends, as she’d planned, she stayed home alone. She waved to people who walked past her place at Hillside Retirement Center, but accepted no hugs, no handshakes, no 100th birthday busses.

It was fine, she said. “I’m as happy as can be.”

Besides, she was doing her part, along with other McMinnvillans, to control the spread of coronavirus.

Signs of the times, said Rohse, who’d been researching earlier pandemics for this week’s “Rohse Colored Glasses” column.

She walks to another building on the Hillside campus to pick up her to-go dinner each night, saying “this certainly interferes with one’s routine.” But she agrees people should stay home and observe social distancing rules, as do her neighbors at Hillside.

And the practice is paying off: “We don’t have a single case here,” she said, praising the retirement center staff. “They’re being careful of us.”

She admitted, like other Americans, she is “rebellious.”

“I’m so used to having freedom,” she said.

Yet this is not the first time Rohse’s freedom has been temporarily suspended. She’s been locked up — or rather, locked down — before.

As a child in the late 1920s, Rohse contracted scarlet fever.

Penicillin had not yet been discovered, and the contagious bacterial disease was considered very dangerous. “We had to be quarantined; the whole family,” she recalled.

The doctor placed a huge white sign with red letters on the door of the Dahl house in downtown Molalla. “I remember looking at it every day,” she said. “No one could enter, and we couldn’t leave.”

Despite the danger and fear it represented, she felt proud of that sign. Other children would walk by the house just to see it.

“I felt pretty special,” said Rohse, who had a mild case of the disease. “It was fun to have scarlet fever!”

That was a child’s perspective, of course. Her parents surely didn’t think it was fun; quite the contrary.

They had lost a child a few years previously to the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918. “My brother, Howard, must’ve been about a year-and-a half-old,” Rohse said. “My mother never liked to talk about it.”

She said she’s glad the coronavirus doesn’t seem to be affecting children like that flu did.

After she recovered from scarlet fever, Rohse moved with her family to Eastern Oregon.

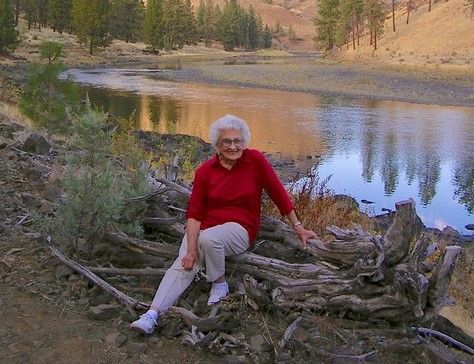

She often writes about her life on a ranch near the John Day River in her column that appears weekly in the News-Register’s Connections section. She has been producing the column for more than 40 years with no plans to stop.

She also has written hundreds of articles for various publications. She was only 9 or 10 when she sent her first submission, an article about her World War I veteran grandfather, and a proposed bonus for vets. It earned her first rejection letter, too, but she kept trying and soon was widely published.

She has collected versions of her columns into a book, “Poverty Wasn’t Painful: Depression Recollections of Eastern Oregon Ranch Life.”

Living in the tiny town of Monument, Rohse said, she didn’t realize her family and neighbors were poor. They had plenty of food, thanks to the natural abundance of the land.

They were blessed with books, too. People shared reading materials, and her mother requested more from the state library, since neither the city nor the school had a library of its own.

“It was just like Christmas” when the big box of books arrived, said Rohse, who loved reading from an early age.

After graduating in a class of four, Rohse used her scholarship money to attend Albany College, a Presbyterian school and a forerunner to Lewis & Clark College. Her future husband, the late Homer Rohse, was a fellow student.

They married as World War II started. After the war, both returned to school at the University of Oregon, he to finish his bachelor’s degree, she to work on a master’s in advertising.

The war not only interrupted college; it also entailed some restrictions to Rohse, as well as other Americans.

Families were told to keep their curtains drawn at night, for one thing. Visible lights might signal enemy planes on attack runs.

Rationing was in order. Everything from sugar to gasoline was in short supply, and families were issued stamps so they could purchase portions.

“I went without shoes, because we had shoe stamps, too,” Rohse recalled. “My mother saved her fat from bacon in the morning, because she couldn’t get other fat for cooking.”

When it came to rationing, Rohse and her husband were in a good position, though.

Homer had enlisted in the Army Air Corps before the war started. Just after Pearl Harbor was attacked on Dec. 7, 1941, he received a telegram ordering him to report to California immediately.

“He managed to get on a train” heading south from Portland, she said. “Even though it was the first days of the war, the train was put on side tracks all the way down because already munitions trains were getting priority on the main track.”

The Army was happy to see Homer, she said, because he already had his pilot’s license. He began training fledgling pilots.

“That was fine for us,” she recalled. “I got to go down and be with him.”

She followed him from California to another base in New Mexico, where he again trained aviators and flew himself. The townspeople there showed their gratitude to the airmen in many ways.

Butchers saved their best meat, even steaks, for the pilots, she said. Liquor sellers did the same with their products.

“That definitely helped the war effort,” she said.

After the war ended and they finished school, the Rohses settled in McMinnville in 1947. He joined the Telephone-Register, a forerunner of the News-Register, and she became the paper’s society editor.

After work, she was involved with the Yamhill County Historical Society, Friends of the Library and other community groups. She became the first woman to serve on the McMinnville City Council.

And she volunteered as a plane spotter.

She would climb to the top of the old Yamhill County Courthouse, a multi-story building topped with a bell tower on the site of the current courthouse. She brought a deck of pictures and silhouettes of planes, so she could distinguish American aircraft from those that shouldn’t be flying over the county.

“I wasn’t sure what we were supposed to do if we saw an enemy plane, though. Run downstairs to tell someone?” she said, recalling there was no phone in the bell tower and, of course, no cellphones.

Rohse counts herself lucky never to have been pressed into making a report.

“It was a precarious situation for McMinnville to be in my hands,” she said, laughing. “Thank goodness I never had an incident.”

Recalling how she — and many, many others — volunteered and sacrificed during and after World War II made Rohse think of what people are doing for others these days.

“People are helping others during this pandemic, too,” she said.

Rohse knows of many examples around McMinnvile and beyond. Here’s just one:

She and several friends usually gather at the same table in the dining hall at dinner. They love their waitress, who knows their habits and preferences. She’ll have V-8 juice and soup on the table when Rohse arrives.

Now that meals are being served to-go, Rohse takes them home and dines in front of the TV (She’s “kind of addicted” to the Rachel Maddow show on MSNBC, she said).

One day, she opened her food bag and found a note from her waitress.

“I miss seeing you so much,” the waitress wrote. “I hope you are happy and well.”

Rohse was touched.

“Such the nicest thing,” she said. “When you’re lonesome and don’t see people, things like that mean so much.”

Comments

oldeee

I climbed those old stairs as well. My grandmother was Beryl Gubser's secretary in those days. Never did see any Korean planes. I was probably 8 at the time. And Mitch on the Valley Forge trip, and your place on the lake.

treefarmer

I have read and enjoyed her column for many years. Her words and memories entertain and inform, her sweet nostalgic stories paint rich and often relatable history. It is so nice to learn more about her travels through life, as well as the celebration of a century spent in comfort and safety - albeit with friends at a distance. Virtual hugs will be redeemable in the future, and they will be worth waiting for!

Write on, Ms. Rohse, and thank you!

Joel

Thanks for being such a great example to all of us in the younger generations coming up behind you, Mrs Rohse. You are a true inspiration!

A New Generation

I frequently enjoy your column and thank you for your refreshing and positive prose!

You're a local treasure!